Ten years of spotting trends

Ten years of spotting trends

What happened with the trends we have written about during the years? Have the Schibsted Future Report been able to foresee where they went? For ten years now we have produced the report – we celebrate this with looking back and reflecting over the changes we’ve seen.

Ten years of spotting trends

What happened with the trends we have written about during the years? Have the Schibsted Future Report been able to foresee where they went? For ten years now we have produced the report – we celebrate this with looking back and reflecting over the changes we’ve seen.

Serendipity opens up your mind

Do you recognise the feeling of not knowing where an idea came from? Suddenly it was just there, perhaps because you let your mind wander in unplanned…

A decade of visions – and a few failures

Eternal life, the metaverse, Google glasses: they came, they saw, but did they conquer? For the past ten years, the Schibsted Future Report has pried open the…

Favourite songs from the last decade

In this tenth edition of the Future Report all authors have chosen their favourite songfrom the last decade. Listen to them all on Spotify.

10 years in pictures

Which are the most memorable and best pictures from the last decade? As Future Report celebrates its tenth anniversary we have looked back and gathered…

Machines like us - a brief history of artificial intelligence

Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

“AI is a bigger threat than climate change”, “AI could cause ‘civilisation destruction’”, “Humanity is failing the new technology’s challenge.”

As OpenAI launched ChatGPT in 2022, not only did people envision amazing new ways to use the technology for the good of humanity, but many AI scientists expressed grave concern that the technology would be used to flood the internet with disinformation or worse, that machine intelligence was about to surpass human intelligence, presenting questions we are not yet ready to answer.

Many have speculated that low-level jobs will soon be taken over by AI. But no longer are only simple, repetitive occupations at risk. Lawyers, physicians, artists, writers… as artificial intelligence approaches the human level we all should worry about – or look forward to – machines replacing us in the workplace.

I recently spoke to Max Tegmark about these developments. He is the author of “Life 3.0,” a professor at MIT and a renowned AI expert, and he is profoundly worried. Tegmark has been campaigning against nuclear weapons for years, but at present, he considers artificial intelligence an even greater existential risk. If we choose to replace ourselves, and let machines do all our work for us, the human species may simply lose the desire to carry on and to procreate. But why, Tegmark wonders, would we want to replace ourselves with machines?

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

In fact, this question echoes through the ages: Why have scientists and alchemists for so long strived to create not just useful machines, but machines like us?

The pursuit of artificial intelligence is not about merely making efficient tools, like calculators and word processors. It is about mimicking human intelligence, a quest to equal or even surpass it. In essence, turning the myth of creation on its head, making humans the creators of new life through intelligent design. This dream has ancient roots.

An awesome bronze giant

The Greeks told of the divine smith, Hephaestus, who forged automatons to serve its masters. Talos is the most famous of his creations, an awesome bronze giant who patrolled the island of Crete, protecting it against pirates. At Alexandria, the Egyptian scholar Heron built a spectacular array of automata for the theatre. Not intelligent, naturally, but appearing alive.

Around the thirteenth century and onward, many learned men, scholars and occultists were rumoured to possess mystical contraptions known as “brazen heads,” mechanical heads covered in bronze, which could answer any questions put to them. This may have been a legend borne out of the ignorance and jealousy of their scholarly wisdom. No evidence of any scientist or magician creating such a device exists. But soon automatons of a less supernatural kind became all the rage among the European aristocracy.

These cleverly constructed machines were no more than mechanical divertissements made of cogwheels and springs, inspiring awe and wonder. Magic tricks, to entertain guests, rather than actual dark arts. But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

Indeed, in the sixteenth century, the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus claimed to have created a living, breathing homunculus by burying human sperm in horse manure for 40 days, magnetizing it, and then feeding it human blood for 40 more weeks. This little humanoid was said to work as an assistant to its master. Paracelsus promised, in words that could very well refer to the creation of artificial general intelligence far in the future:

“We shall be like gods. We shall duplicate God’s greatest miracle – the creation of man.”

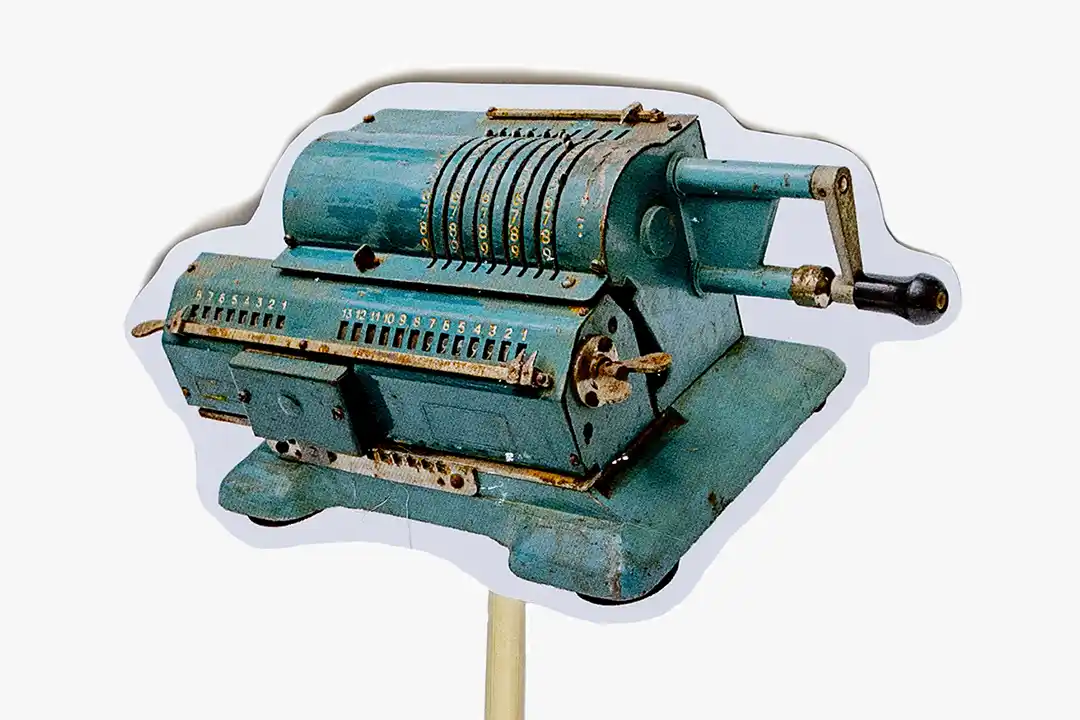

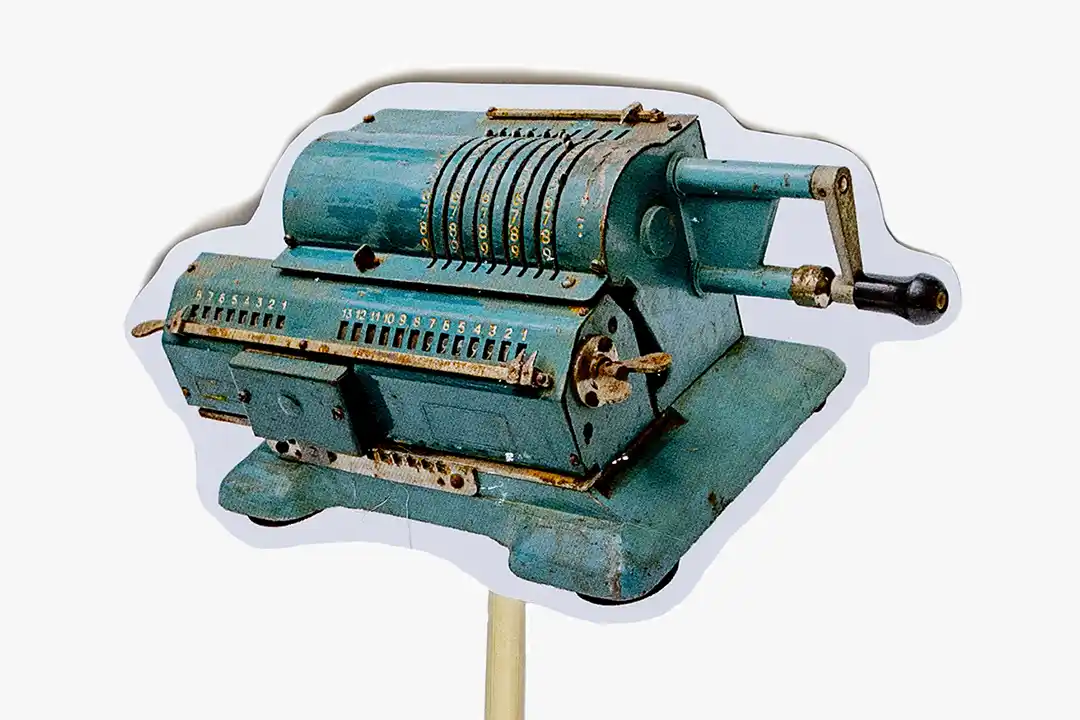

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

In 1818, a sensational horror novel was released that tickled the imagination of thousands of readers. “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley, is the tale of a modern scientist following in the footsteps of alchemists like Paracelsus, consumed by the idea of creating an artificial man through scientific means. The Italian biologist Luigi Galvani had recently discovered that electricity is the means by which the brain sends signals to the muscles, so Shelley had Viktor Frankenstein animating his creature by electric current from a burst of lightning. The result, of course, is Frankenstein’s monster – a huge man, terrifying to its creator and woefully unhappy, who goes on a murderous rampage. The tale may serve as a warning of humankind’s troubles in controlling their greatest inventions.

Starting point of modern computing

Many historians would cite Charles Babbage’s designs for the Analytical Engine as the starting point of modern computing. In the 1830s, Babbage, a British inventor, engineer and mathematician, came up with two designs for machines capable of performing mathematical calculations. The first, called the Difference Engine, was funded by the British government and Babbage himself, but the project was never completed.

The second, called the Analytical Engine, was even more ambitious, and funding was hard to come by. Along with his companion Lady Ada Lovelace, he came up with different schemes to fund the project. At one point they proposed a tic-tac-toe-playing machine to entice investors, then they considered building a chess machine. Before they could build it, however, they came up with an even better idea. They would build the perfect system for betting on horse races, to fund the completion of the Engine. The scheme was meticulously planned by some of the brightest minds in England and ended in spectacular failure. Soon Lady Lovelace was deep in debt and rescued not by any ingenious machines but by her kind mother.

The Analytical Engine, like its predecessor, was never completed. But Babbage’s designs, along with Lady Lovelace’s ruminations on how the Engine would in theory be able to not only calculate numbers but to have those numbers to represent anything – for instance sounds in a musical composition – was an important step in the creation of the universal computer.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

It would be another century before such a computer was finally realised. The world’s first programmable computer was built in the late 1930s by the German engineer Konrad Zuse. He called the mechanical, motor-driven machine the Z1. Although it was the first computer to be finished, many other engineers were tinkering with computers around the world. At this time, the field of psychology was also starting to understand the human mind as a biological network, and piece by piece figure out its workings. Perhaps the brain was best understood as a machine? And if so, might not a machine such as the computer, in the future, be able to perform the same work as the brain?

With these questions in mind, scientists were again starting to entertain ideas about thinking machines, mimicking human thought and behaviour. Their ideas were collected under names such as “cybernetics,” “automata theory” and “complex information processing”. It was not until 1956 that the American scientist John McCarthy came up with a new name for the field, that proved to be sticky: “artificial intelligence.” That summer he joined 19 other prominent academics at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire for a workshop brainstorming about the exciting new field.

Creating a computer mind

The participants of the conference were engineers, psychologists, neuroscientists, mathematicians, physicists and cognitive scientists; an interdisciplinary brain trust well suited to taking on the challenges of creating a computer mind. Their mission statement – brimming with the naïveté that comes from not yet having tried and failed – outlines their lofty ambitions:

“Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans and improve themselves.”

The participants were confident that they would make great strides in this direction during the two-month workshop. It would be a stretch to say that they achieved their goal, but during those long discussions at the Dartmouth Math Department, they at least firmly established the new field of AI.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Human-level machine intelligence would turn out to be far harder to achieve than the early pioneers imagined. During the following decades, AI hype would be followed by AI winter in a cyclical pattern. Several prominent AI researchers, among them Marvin Minsky, had predicted human-like intelligence by the 1980s. When those predictions were proven wrong, some were deflated, but the Japanese government was eager to have Japan take the lead. In 1981, Japan initiated the Fifth Generation Computing Project, pouring 850 billion dollars into AI research, with the stated goal of creating machines that could carry on conversations, translate languages, interpret pictures and reason like human beings.

Progress was made during this time, primarily with limited systems tuned to play chess or give expert advice in narrow fields of inquiry. But anything even vaguely resembling the dynamic and wide-ranging intelligence of humans remained out of grasp. After the Fifth Generation Project came to an end, without fulfilling its promise, the field again found itself at a low point late in the 1990s.

Luckily, an offshoot of AI research was about to gain new traction. In parallel to the mainstream research going on at prestigious universities, well-funded government programs and hyped-up companies, some scientists had taken an interest in artificial neural networks. The network architecture was thought to resemble the human brain, offering new ways of representing machine thoughts compared to the strictly algorithmic manipulation of symbols of conventional AI systems. A neural network could be trained on appropriate data sets, much like a child learns, until its maze of internal connections becomes suitable for its designated tasks.

A fatal flaw

Artificial neural networks had a fatal flaw, however. As soon as you started to scale a network to do something interesting, its complexity increased exponentially, and the system ground to a halt. The computer hardware of the time, with architecture very different from human brains and far less processing power, simply could not keep up. So, this line of research remained theoretical, dormant for decades until, deep in the 2010s, the time had come for the AI field to enter a new era of machine learning.

Three developments of the new millennium came together to finally make neural networks practical:

Computer hardware kept getting faster, smaller and more energy efficient, as predicted by Moore’s Law.

Computer scientists developed more sophisticated architectures and algorithms for artificial neural networks.

An immense trove of digital text, images and sounds accumulated online, an all-you-can-eat buffet of information for neural networks to be trained on.

Looking back at what was then envisioned, artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name.

With the recent work of DeepMind, OpenAI, Google and Microsoft, we arrive at today’s state of the art. Artificial intelligence may have missed the deadline of Japan’s Fifth Generation Project, but looking back at what was then envisioned – or indeed, what the Dartmouth Workshop sought to achieve – artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name. ChatGPT and its rivals can easily hold conversations with humans; Google Translate and its ilk can translate text and speech in the blink of an eye; and many neural networks not only interpret images but also create beautiful pictures from natural-language prompts.

Several fundamental questions do remain, however. Can these machines truly reason? Can they think? Can they feel? Will they ever?

The French seventeenth-century philosopher René Descartes famously formulated a dualist theory where mind and body are metaphysically separate. He was inspired by the automatons on display in Paris at the time and concluded that mind and body must be different substances. The latter can be replicated by automatons, while the former is singular to man and intimately tied to what makes us us. We think, therefore we are.

Unexpected leaps

With AI science advancing – at times inching forward incrementally, sometimes striding with unexpected leaps – software engineers are getting closer to imitating the human mind as well. Chat GPT has repeatedly defeated the Turing test, designed by the British computer pioneer Alan Turing to settle the question: “Can machines think?”

Refined algorithms, humongous data sets and clever reinforcement learning techniques are pounding at the walls of dualism. Perhaps, as the Dartmouth Workshop proposed, the human mind is a mere machine after all. And if this is the case, why would we not be able to replace it with more efficient machines?

The history of artificial intelligence is a tale of scientific progress, of engineering failures and of triumphs. But it is also the story of our struggle to understand our own minds. Are we truly unique? Are our brains, like our bodies, simply machines governed by electrical impulses? When we dismiss the “thinking” of large language models as simply a series of predictions of what comes next, are we absolutely certain that this does not also apply to human minds?

It seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already.

At this point (as at every point in the history of AI) it seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already. There is still some disagreement about whether we can create feeling machines, however. Conscious machines. Machines that can do and experience everything that a human can and more.

Some aspects of this may be harder than we can foresee. On the other hand, it may be within our power sooner than we think, emerging incidentally as our models become increasingly complex, combining techniques from neural networks with symbolical AI.

Mary Shelley would be delighted to see modern scientists still hard at work trying to realise the ancient dream of godlike creation. The full original title of her famous horror novel is “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.” The subtitle alludes to the crafty Titan from Greek mythology who stole fire from the Olympian gods and gave it to man. Fire, in this old tale, symbolises knowledge, invention and technology – powers Zeus had determined must be reserved for gods and withheld from humankind.

In some versions of the myth, Prometheus gives us more than fire; moulding the human race from clay, he also gives us life. Millennia later, the fire he gave us is still burning bright, and we are now the ones doing the moulding. Not from clay, but from code.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Sam Sundberg

Freelance writer, Svenska Dagbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Light years – The National

Human happiness must be our common goal

“Human happiness must be our common goal”

She thinks we’re discussing AI on the wrong level. And her vision is that everyone should understand how the technology works. Inga Strümke has become a tech celebrity in Norway, much thanks to her bestselling book, “Maskiner som tenker.”

By Ann Axelsson

“Human happiness must be our common goal”

She thinks we’re discussing AI on the wrong level. And her vision is that everyone should understand how the technology works. Inga Strümke has become a tech celebrity in Norway, much thanks to her bestselling book, “Maskiner som tenker.”

By Ann Axelsson

“If you talk about existential risks and appeal to people’s fears, you will get attention,” she says, referring to the dystopian warnings that AI will replace humans and take all jobs.

“These futuristic scenarios are not constructive, and they make it hard to debate the mechanisms behind the technology. What we really need to discuss is how we can develop today’s AI systems according to legislation, our goals, and our values.”

Inga Strümke is an associate professor in AI at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU. She’s also a particle physicist, a frequent public speaker, and a best-selling author. “Maskiner som tenker” (“Machines that think”) has become a bestseller in all categories in Norway.

She also spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. That was a challenge. Until ChatGPT.

“Unfortunately, it takes bad news to get them to listen.”

As a scientist in the field, she of course welcomes progress, and she explains that the scientist’s mindset is to think about what is possible and then develop that.

“That mindset has given us X-ray, GPS, the theory of relativity. And atom bombs. As a scientist, you never know how your findings will be used. That’s where society needs to step in.”

Inga Strümke has spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. She was also a speaker at Shibsted’s strategy summit in October 2023.

Inga Strümke has spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. She was also a speaker at Shibsted’s strategy summit in October 2023.

And she believes that ChatGPT is a perfect example of how bad things can go when you share “fun” new technology openly, without having had discussions about its implications.

“I believe we have a serious problem when pupils are now thinking, ‘Why should I write a text if there is technology that can do it better?’ How will we now make young people understand that an idea starts with a thought in your head and that you need to grow and communicate that idea to get other people to understand it? And if you can’t do that, then you won’t be able to function in society.”

That might sound just as dystopian as the future scenarios. But her point is that we can and we must take the lead here in the Nordics and in Europe when it comes to discussing the role we want technology to play.

“If we can’t manage to figure out how to use what we develop here, then we will end up using solutions developed by tech giants that we are unable to influence.”

Impact across the society

And these discussions, she says, should involve experts from across the board – politicians, social scientists, economists, legal experts, ethics, apart from technologists – since the impact will be felt across all parts of society.

This is also why she thinks it’s so important that as many of us as possible understand what this is about and how the technology works. The things she explains in her book.

“My dream is that anyone can read it. That a woman past 80 would read it and think, ‘I can understand this if I want to.’ I have this passion to empower people on this subject. To make them see that they can look after their own interests.”

New class issues

What also has become clear to her, in discussions after writing the book, is that AI can spur a new kind of class issue. That the world might be divided between those who are able to use the technology for their own benefit and those who aren’t.

“Someone said that AI will not take the journalists’ jobs. But journalists who know how to work with AI will take the jobs from the journalists who don’t.”

Inga got into the science world as a physicist. She wanted to understand the universe. Then, when she took her bachelor’s at NTNU, she noticed there was a field of study on artificial intelligence, and curiosity led her that way.

“My driving force is to find out what is possible. The main reason that I’m still in this field is that I see the consequences, and they are extremely complex.”

Even though she thinks about this complexity day and night, she also finds time to use that curiosity and energy on other things – mainly outdoor activities. Her social media is filled with pictures of her mountain biking, climbing and hiking. And those things are important.

“No matter what happens with technology and politics, there is one important thing that we can’t forget: to have a nice life. Human happiness must be our common goal – if not, nothing else matters. That’s very important to me to remember, every day.”

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Ann Axelsson

Senior Product Manager, Strategic Communication, Schibsted

Years in Schibsted: 25

My favourite song the last decade: Paper Doll – John Mayer

AI for good or for bad?

AI for good or for bad?

How will AI impact our lives and society? Joacim Lund compares it to the breakthrough that came with the internet – and sees many similarities. AI will solve many problems in our daily lives. We just need to make sure it doesn’t create new ones.

By Joacim Lund

AI for good or for bad?

How will AI impact our lives and society? Joacim Lund compares it to the breakthrough that came with the internet – and sees many similarities. AI will solve many problems in our daily lives. We just need to make sure it doesn’t create new ones.

By Joacim Lund

Artificial intelligence is a flop. Ok, not really. But we are talking about it the wrong way.

In Norway, an opinion piece from 1996 pops up on a regular basis. The headline of the newspaper clipping is crystal clear: The Internet is a flop.

Every time it appears, people have a good laugh. But the person who wrote it (incidentally, a reader I keep getting meaningful emails from) wasn’t irrational in his argument. He believed that people who work on computers will get more than enough of it during office hours (this definitely applies to some of us), that humans are social beings and, moreover, that it would not be profitable for business to offer their services online.

“When we rent our videos, we will visit the rental store and make our selection in visual surroundings,” he opined.

27 years later, much of the debate around artificial intelligence is not entirely dissimilar. People are either for or against artificial intelligence. They think it’s either good or bad. They think it will eradicate us or not. They want to stop it or let it be.

As new technologies arrive – the sceptics speak up. New habits sometimes take time to accept.

As new technologies arrive – the sceptics speak up. New habits sometimes take time to accept.

At the same time, AI developers from around the globe are creating autonomous weapons, racist algorithms and extreme surveillance systems that challenge human rights. Other AI developers are creating systems that revolutionise medical research, streamline the public sector, or help keep the temperature of the planet below boiling point. And everything in between.

The possibilities seem to be endless. So, shouldn’t we rather be talking about how AI can be used responsibly?

It’s changed everything

Today, everyone knows that the internet was not a flop. The authorities communicate with us using the internet. Ukraine and Russia are bombing each other using it. The propaganda war is almost exclusively waged online.

But perhaps even more importantly: the internet solves problems and has made life easier for most people. I charge my car online, pay bills and rent my videos (but sometimes I do long to go back to discussing movies with the movie nerd who worked on Bislet Video instead of getting flimsy recommendations by an algorithm).

I listen to my music online, remotely activate the heaters at the cabin, where I can also stream my news broadcasts. People find life partners online and discover like-minded people who also get excited by photography, old Italian scooters, 16th-century clocks, or Talk Talk bootlegs. We have access to everything, everywhere, all the time.

That’s why everyone laughs at the “flop” prediction. He was absolutely certain and he was wrong. But that’s easy to see in hindsight. And it’s hard to predict.

In 1996, people were concerned about Charles and Diana’s divorce and Bill Clinton’s re-election. Who could have imagined that Diana would die in a car accident in Paris a year later? Or that two years later, Bill Clinton would be explaining why his sperm was on a dress?

Or that the internet was going to change everything?

Tomorrow is only a day away

I have no idea how artificial intelligence will have impacted society, people and the lives we all live in 2050. But I see several similarities between the internet in 1996 and artificial intelligence today:

Artificial intelligence solves problems and will make life easier for most people. Artificial intelligence is changing assumptions.

Also for people who don’t have good intentions.

“Whoever takes the lead in this field takes the lead of the world,” Putin said during a live address to 16,000 schools at the start of the school year in the fall of 2017. By “this field” he meant artificial intelligence. Xi Jinping had recently launched an ambitious plan to make China a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

It almost makes you want to just ban the whole thing. Impose international sanctions and throw the baby out with the bathwater. The problem is that artificial intelligence opens up so many positive possibilities as well.

Things like evaluating X-rays, AI can solve much faster and better than humans.

Things like evaluating X-rays, AI can solve much faster and better than humans.

The toe is broken

I was once playing with my son. I chased him around the apartment, arms straight ahead, like a zombie. As I made my way around the kitchen table, my little toe hooked onto a chair leg. There was no doubt that the toe was broken. It pointed straight out to the side. Still, I spent most of the day in the emergency room.

The reason for this was a bottleneck in the system.

When people come in with minor fractures or just a suspicion that they’ve broken something, for that matter, an X-ray is taken. A doctor (the bottleneck) must study each individual image to see if there is a fracture or not. If there is no fracture, the doctor sends the patient home. If there is a fracture, the patient is placed somewhere on a priority list.

However, minor fractures are not life-threatening. If there is a lot to do in the emergency room, the X-rays will be given low priority until there is more time to look at them. When the doctor finally has time, he or she will study the picture and determine that there is no fracture – in about 70% of cases. The patient, who by then may have waited seven hours, is then told to go home, take two ibuprofen and three glasses of red wine (which my dentist once recommended), and turn on Netflix.

It’s things like this that artificial intelligence can solve much faster and better. And it’s already doing it, actually.

Level up

The other day I was visiting a hospital in Bærum, just outside Oslo. An enthusiastic, young, bearded radiologist pointed to an X-ray image on a screen in front of us. The picture showed a foot, and it looked quite similar to the picture taken once upon a time of my foot (except that the little toe didn’t point straight out to the side).

But one thing was different. The image had been assessed by an artificial intelligence.

Above the ankle bone, a yellow square had been drawn, lined with the text “FRACT.” That means there’s a fracture there. The software goes through all the X-rays as they come in. Seven out of ten patients are told immediately that they can go home. The rest automatically end up in a priority queue.

Doctors do not have to spend valuable time finding out that everything is okay, and patients do not have to wait. This is an extreme efficiency improvement in a health service that will experience greater and greater strain in the decades to come.

Should this have been banned? Some think so.

Sense and sensibility

A few months earlier, two Norwegian politicians warned that artificial intelligence leads to everything from polarisation to eating disorders, and perhaps even the extinction of humanity. The government should immediately “impose a public sector moratorium on adopting new commercial tools based on artificial intelligence,” they argued.

This is an absurd approach to artificial intelligence. The pressure on the healthcare system only increases as people age. To have any hope of maintaining good health services for the population, we must make use of the tools at our disposal. The AI tool at Bærum Hospital happens to be delivered already fully trained from abroad. All patient data is deleted, so as to avoid all privacy issues. Of course, there shouldn’t be a ban on such things. But the two politicians still had a good point:

“The development of AI has for a long time taken place without adequate regulation from the authorities.”

Now it’s happening

There has been a Wild West approach from the tech companies. Naturally. Development is rapid, and work on laws and regulations is slow. But the EU has been working diligently on the issue.

The EU’s first draft regulation of artificial intelligence, the so-called AI Act, was presented two years ago. It is likely to be formally approved within 2023. The EU is adopting a risk-based approach. For services that pose a low risk, it’s full speed ahead. Unacceptable risk means it’s prohibited. And for everything else in between, there are two more levels: acceptable risk and high risk.

The purpose of the AI Act is to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are safe and respect fundamental rights and values. This means, for example, that facial recognition in public spaces is banned. It’s not allowed to single out citizens for the authorities to keep an eye on in case they do something illegal. Stuff like that.

AI should be open and honest, not closed and manipulative. The resistance the AI Act has faced from tech companies suggests that regulation is needed. For example, Sam Altman, the man behind OpenAI and ChatGPT, has threatened to pull out of Europe if the regulations become too extensive.

Perhaps now it’s time to revisit the crystal ball.

A willingness to solve problems

In September 2023, Norway’s Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, held a press conference where he proudly announced that his government would allocate one billion Norwegian kroner to artificial intelligence research, to be used over the course of five years. On the same day, the government leaked that it would spend five billion on a new tunnel to shave a few minutes off the drive between two villages in the mountains of western Norway somewhere. But OK, a billion is money too.

A large and important part of the research will focus on how artificial intelligence can be used for innovation in industry and in the public sector. Like in hospitals, when people come in with sore fingers and toes. Or in building applications, so people don’t have to wait several months for the overworked caseworker to get far enough down the pile. Or to provide public services with a faster, larger and better basis for decision-making. Or to improve data security, in fact, and not worsen it.

And in so many other ways that I can’t possibly imagine.

That’s what politics is all about. To follow social developments and govern society in a way that makes it as good as possible for as many people as possible. Norway is just an obvious example because that’s where I live. The same goes for every other country and continent, and globally, for that matter.

As in other areas of society, international resolutions and treaties and sanctions must be adopted to ensure that artificial intelligence is used in a way that solves humanity’s problems, rather than create new ones.

That work is underway.

OK, here’s what the crystal ball says

If I’m going to allow myself to try to look 27 years into the future, to 2050, I’d guess that people are more concerned about themselves and their nearest and dearest, and not so much about what people were thinking back in 2023. But those who bother to read old newspapers might chuckle a bit at the banal discussions we had about artificial intelligence ’way back when.’ And the fact that many were either for or against. Maybe it’ll be the demand for a ban and the call to halt development that everyone will laugh at (try asking Putin to stop the development of artificial intelligence, by the way).

I’m guessing that my future grandchildren will experience an education system much more attuned to each student’s learning disabilities, learning styles and skills. That their health will be taken care of much better than by the GP they see every two years. That potential health problems will be discovered before they become major and serious. I’m guessing the car will be a safer driver than the human. That public transport will be much better adapted to people’s needs. That precise weather forecasts will control the heating in houses. That everyone will be better protected from abnormal activity, whether it’s in their bank accounts or in their apartments. Maybe I won’t have to think about shopping for food or cleaning the house anymore.

I’m guessing it will seem strange that society spent so much time and resources on having people perform repetitive and simple tasks. And that major and important decisions were made on a razor-thin knowledge base.

I am absolutely certain that artificial intelligence will be subject to international regulations. And that artificial intelligence will lead to global, regional, local and personal changes that are difficult to imagine today.

Because by then humanity will know better.

If, of course, it still exists.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Joacim Lund

Technology commentator, Aftenposten

Years in Schibsted: 18

My favourite song the last decade: Bråtebrann – Kverletak

Unleashing the potential of AI in news

Unleashing the potential of AI in news

In the fast-paced digital world, the news media industry stands on the brink of a revolutionary shift. AI will shape the future of journalism and content creation. Ian Vännman from Schibsted Futures Lab predicts several phenomena that will drive the transformation, as he looks into the technology behind it.

By Ian Vännman

Unleashing the potential of AI in news

In the fast-paced digital world, the news media industry stands on the brink of a revolutionary shift. AI will shape the future of journalism and content creation. Ian Vännman from Schibsted Futures Lab predicts several phenomena that will drive the transformation, as he looks into the technology behind it.

By Ian Vännman

AI is the catalyst for a transformational wave that’s redefining our reality, akin to the monumental changes brought about by the birth of the microprocessor, the emergence of personal computers, the spread of the Internet, and the ubiquity of mobile phones.

To comprehend this future better, the Schibsted Futures Lab team delves into and explores recent technological advancements. We function as scouts, scanning beyond the Schibsted horizon and using our insights to influence our colleagues to apply emerging technologies in our businesses. We also identify and examine smaller breakthroughs, as they provide clues about plausible futures.

Breakthroughs that spark innovation

History has taught us that seemingly minor technical breakthroughs can spark innovations that, over time, dramatically reshape our world. Consider, for example, Intel’s creation of the microprocessor in 1971. This paved the way for Apple to launch the personal computer in 1977. The convergence of these technologies with Stanford’s invention of TCP/IP, the networking protocol that forms the backbone of the internet, truly took off when the World Wide Web became globally popular with Netscape’s introduction of its web browser in 1994. These innovations, combined with the GSM digital mobile networking standard developed in Europe in 1987, led to the birth of the smartphone.

Thus, minor breakthroughs converge with other advancements and innovations to generate new innovations that, over time, revolutionise the world.

History has taught us that seemingly minor technical breakthroughs can spark innovations that, over time, dramatically reshape our world.

History has taught us that seemingly minor technical breakthroughs can spark innovations that, over time, dramatically reshape our world.

Recently, the Futures Lab team has been delving into groundbreaking technologies such as neural radiance fields (NeRFs) and diffusion models. NeRFs is an impressive AI-based technology that allows us to construct 3D environments using only 2D images. In essence, it enables us to use standard cameras to generate 3D objects and environments, as showcased in Luma’s apps. Diffusion models are being used to create artistic and lifelike images with only text as input, as seen in applications such as Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable Diffusion.

While these technologies are impressive in their own right and seem almost magical from a user perspective, they pale in comparison to the innovations spurred on by the transformer architecture. This technology, developed by Google in 2017, now underpins all the leading chat-based AI services, such as ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Bard and Meta’s open-sourced Llama.

The real magic

The transformer architecture is leveraged to create large language models, often referred to as LLMs. These LLMs are trained on enormous volumes of text data, enabling them to form artificial neural networks that capture and store patterns from the data. The real magic lies within these LLMs. To draw an analogy, if ChatGPT were a car, the LLM would be its engine.

Building on the transformer architecture, OpenAI introduced another breakthrough: a new type of LLM known as Generative Pre-trained Transformers, or GPT, as in ChatGPT. Fast forward to 2023, OpenAI and its contemporaries have enhanced GPT with the ability to build tools. In simpler terms, GPT can now generate and execute code to accomplish tasks.

The advancements we’ve made in the past 50 years will likely pale in comparison to what we’ll achieve in the next 50 years, or even the next 15 years.

The advancements we’ve made in the past 50 years will likely pale in comparison to what we’ll achieve in the next 50 years, or even the next 15 years.

Several academic studies have already explored the impact of using ChatGPT across various professions, including law, customer support, programming, and creative writing. The consensus is clear – AI significantly enhances the productivity of lower-performing individuals, enabling them to accomplish more with better quality. High performers see less improvement, and in some cases, even a drop in productivity. Interestingly, early indicators suggest this productivity boost is consistent across many, if not all, white-collar disciplines.

This can be attributed to two primary factors. First, chatbots have become remarkably adept at simplifying complex tasks. Second, Gen-AI enhances creativity. While there’s ongoing debate in the scientific community about whether large language models can truly be creative, from a productivity standpoint, this is a moot point. After experiencing ChatGPT’s “creativity,” it’s clear that it’s quite adept at it.

Something bigger

But is the so-called AI revolution merely about increasing productivity by using ChatGPT and its counterparts in office work? Or is there something bigger at play here?

Comparing the CPU, the central processing unit of a computer, with the human brain, we find that they complement each other remarkably well. The CPU excels at rapidly executing instructions provided in code with structured data – tasks that humans find challenging.

Conversely, we humans excel at learning, a capability entirely absent in a CPU. We possess agency, intuition, creativity, and are multi-modal, meaning we process input and output through most of our senses.

The LLM sits somewhere between these extremes. It’s as fast as a CPU, but also capable of learning in the sense that it can be trained and fine-tuned. It possesses contextual understanding, a characteristic more akin to our brains than a CPU.

Low costs

The key takeaway is that we now have access to human-like intelligence at nearly zero cost. It’s more than just about chatbots. Large language models enable us to infuse human-like analysis, creativity, decision-making and more into workflows and processes at virtually no cost.

With this perspective, the advancements we’ve made in the past 50 years will likely pale in comparison to what we’ll achieve in the next 50 years, or even the next 15 years, for better or worse.

How can all of this play out more concretely, in one of Schibsted’s core business areas – news media?

The answer to this is that its practical implications will be vast and far-reaching. The expected transformations will challenge the very core of our traditional business models. To grasp the full breadth of AI’s potential impact, let’s first consider the fundamental business structure of the industry.

Most online businesses can be simplified into three core activities:

- Creation of goods

- Customer acquisition

- Distribution of goods

- From a financial perspective, these activities respectively translate into:

- Cost of goods sold

- Sales and marketing expenses

- Other operating expenses

Historically, the advent of the internet drastically reduced distribution costs in the news media, triggering substantial shifts in how content reached consumers and removing most barriers to entry into the market. Now, as we usher in the era of AI, we stand on the precipice of another profound change: a potential collapse in content creation costs. The ramifications of such a shift could be as transformative, if not more so, than the internet’s earlier influence on the business models and the broader industry landscape. In the short term, I predict several phenomena that are set to drive our transformation:

Democratisation of programming

Anyone can develop software using tools like ChatGPT and Replit. All it requires is a bit of curiosity and courage. This democratisation signifies not just more efficient programming, but an increase in the number of programmers, which will further accelerate digitalisation and innovation. As Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, puts it:

“I think the world is going to find out that if you can have ten times as much code at the same price, you can just use even more.”

Automation of content creation

Content with predictable production processes and performance, often format-driven, such as news summaries, listicles and interviews, will likely be generated either entirely by AI or more commonly in collaboration with journalists.

Unbundling of research and narrative

Traditionally, journalism involved researching facts and weaving them into a cohesive narrative. With AI, we can separate these processes. For instance, we can publish research material alongside articles, enabling readers to explore the underlying research through an AI-driven chat interface. Newsrooms may even have teams dedicated solely to establishing and verifying facts and other information building blocks, which are then used to automatically create content using AI.

Writing of previously unwritten stories

Many individuals possess important stories that remain untold due to a lack of competence in content production. With AI, these barriers between lower and higher performers are reduced, allowing many more voices to be heard.

Personalised consumption

Every individual has unique consumption preferences. With AI’s ability to transform text into various formats, we can cater to these individual needs more effectively, especially when mastering the arts of unbundling research and narrative, as well as the automation of content creation.

With the collapse in costs and barriers in distribution and content creation, customer acquisition becomes the primary competition area for both new and incumbent brands.

To succeed in this new paradigm, I’ve identified at least four distinct, but not mutually exclusive, strategies that news media brands can deploy.

1. Creating an addictive product

Develop a service so engaging that it captures users’ attention far more than traditional news outlets. The prime example is TikTok, which holds users’ attention for an average of 90 minutes daily. Achieving this is extremely, challenging, likely impossible, but the payoff is tremendous if accomplished.

2. Fostering a movement

Tap into deeper emotions such as fear and hope to capture audiences’ energy and passion, generating extraordinarily high engagement and loyalty. Fox News, for better or worse, has done this. There is no doubt that in these times of high uncertainty, audiences are yearning for hopeful narratives.

3. Nurturing a trusted brand

This is the go-to strategy for established brands. Establishing and maintaining credibility in an era of information overload should be rewarding. However, in a future hostile media landscape, no matter how strong the brand is, brands will require greater degrees of discipline, transparency, and accountability than before.

4. Building a community

In a world of increasingly personalised experiences, individuals will seek shared interactions and rewarding experiences. This insight isn’t new for news media, but most previous attempts to build communities encountered scaling issues as the community grew, leading to its downfall. This paradox may be resolved if we can leverage AI to address the challenges that arise as the community expands.

Technology of the present

AI is not a technology of the future anymore; it’s very much a technology of the present. Every media organisation must actively engage with AI tools and platforms. Training your teams on platforms like ChatGPT or similar AI tools can lead to innovative storytelling techniques, streamlined content production, and a deeper understanding of audience behaviour.

On a personal level, embracing this new paradigm means integrating AI into your daily routine. You need to incorporate it into your life to such an extent that you automatically turn to it whenever you face challenges that require collaboration, or that can be solved faster and more effectively than you or your colleagues can do on your own. Only when it becomes an integral part of your life will you be able to fully understand it and its potential.

Rethink the pipeline

The barriers to software development are being lowered every day. Embrace this democratisation by encouraging your teams to experiment. Host internal hackathons or workshops. Foster a culture of prototyping; this not only breeds innovation but also promotes a fail-fast mentality in which learnings are quickly integrated.

With AI’s capabilities, media organisations have the opportunity to rethink their content production pipeline. Centralising certain production elements can help maintain consistency while leveraging AI can ensure content is tailored to audience preferences. Moreover, AI can assist in identifying content trends and predicting audience interests.

The transformative power of AI in the journalism industry is undeniable. We stand at a crossroads, facing a horizon with enormous uncertainty, limitless opportunities and inevitable challenges. The technological power that AI presents has profound implications on how we produce, distribute and consume news. As AI shapes a new paradigm for humanity, it becomes imperative for the journalism industry to not just adapt but lead the way. By wholeheartedly embracing AI, media brands can redefine their narrative in this new era. This journey won’t be without pitfalls, but the rewards – both for the industry and society at large – are immense. The future of journalism, powered by AI, awaits.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Ian Vännman

Strategy Advisor, Schibsted.

Years in Schibsted: 23

My favourite song the last decade: I Don’t live Here Anymore – The War on Drugs

Help! My smartwatch became a PT from hell

Help! My smartwatch became a PT from hell

Optimising your body and mind has never been easier. But is it really that healthy to measure our health down to every heartbeat? Wearable technology, pressure to perform, a growing wellness industry and AI are becoming a toxic cocktail.

By Tobias Brandel

Help! My smartwatch became a PT from hell

Optimising your body and mind has never been easier. But is it really that healthy to measure our health down to every heartbeat? Wearable technology, pressure to perform, a growing wellness industry and AI are becoming a toxic cocktail.

By Tobias Brandel

“People are so self-absorbed.” My mothers’s reaction when I showed her which of “my” articles had performed best lately was not quite the maternally, uncritical praise I had expected.

Last autumn, I took on the role of science editor after several years as head of Svenska Dagbladet’s political coverage. To clarify what type of articles I am now editing, I showed her a recent summary of successful headlines from the managing editor’s endless collection of PowerPoint presentations. Among them: “You control the success of your child – but not the way you expect”, “Mediterranean eating habits beat all other diets in the long run” and “Henrik, 42, follows the most effective method of weight training according to research.”

A slightly more refined way of expressing my mother’s nevertheless rather sharp observation is that SvD’s science coverage focuses quite a bit on “useful science.” Stuff that helps people in their daily lives.

People want to perform in all areas

Our readers are interested in their own well-being and development; in health, nutrition, fitness, psychology and the process of learning.

These days, this type of journalism accounts for notably large sections of international news sites such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. People want to perform in all areas of life – career, family, leisure time, health.

As a freshman science editor, I soon discovered the role also included the specific requirement of presenting new scientific findings in the area of fitness and training every week. A slightly prejudiced – and totally incorrect – idea of the type of fitness articles that should work in a “Grey Lady” newspaper like SvD would be… well, home exercises for seniors.

However, I quickly came to the realisation that, in terms of their physical status, our fitness-interested readers perform well above the average exerciser, aiming for the elite. Articles on heavy gym workouts are appreciated the most.

When McKinsey recently published a special report on the wellness industry, it was valued at 1.5 trillion USD, with an annual growth rate of 5–10%.

When McKinsey recently published a special report on the wellness industry, it was valued at 1.5 trillion USD, with an annual growth rate of 5–10%.

Overall, SvD’s fitness pieces are often the best performing of all articles on the site during the day of publication, regardless of which indicators you look at – subscription sales, page views among existing subscribers, scroll depth and so on. At least in January (New Year’s resolutions must be fulfilled!), May (dawning beach panic!) and August/September (time for a fresh start after a wine-soaked holiday…).

The pattern is similar when it comes to the many articles we publish on research related to nutrition and diet. How should I eat to be as healthy and enjoy as long a life as possible?

Turning our gaze from the newspaper industry and looking more broadly at the tech sector, there is perhaps one small gadget above all else that is driving developments in terms of people’s persistent struggle to improve themselves.

The annual trend survey “Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends” from the American College of Sports Medicine is something of a bible in the fitness industry. The top spot in 2023 went to wearable technology, a term that has consistently placed itself at or near the top of the survey results each year since it was first introduced on the list in 2016. By no means a coincidence, the first version of Apple Watch had been released on the market one year earlier.

The next phase is around the corner

Heart rate monitors and more basic types of fitness trackers have, of course, been around much longer than that. But as usual, it was Apple who perfected the concept and raised the bar with its version of the smartwatch, which quickly became the market leader.

Now the next phase of the wearable technology revolution is around the corner, with the AI hype reaching this sphere.

The spreading of rumours regarding Apple’s upcoming products is, in itself, something of a journalistic genre. Much of the recent speculation has concerned an “AI-based health coach” for Apple Watch. No such innovation was to be seen when the latest version was released in September 2023, but the likelihood is that it will appear in 2024, or perhaps it will have already launched by the time you read this.

The 2023 top spot in the annual “Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends” from the American College of Sports Medicine went to wearable technology.

The 2023 top spot in the annual “Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends” from the American College of Sports Medicine went to wearable technology.

The Apple Watch has evolved into a rather impressive health product in recent years. Today, it can measure your heart rate, body temperature, how much time you spend sleeping and standing, calculate the amount of calories you burn, and so on. Furthermore, the most advanced versions are also able to execute an ECG, measure your blood oxygen level and calculate your menstrual cycle. However, in these areas, the scientific evidence is more dubious (Apple provides a disclaimer in the footnotes that these functions are not for “medical use”).

AI technology is, of course, already being applied. For example, Apple uses machine learning to detect irregularities in heart rate or if the wearer is involved in a serious car accident (whereupon the watch automatically calls the emergency services).

Future areas

Some potential future areas of development for artificial intelligence in wearable technology include:

Detecting a range of health problems – acute or long-term, physical as well as psychological – by studying patterns, deviations and trends. It may also be possible to provide healthcare professionals with assistance in making diagnoses.

Creating personalised training, dietary and treatment programs based on each individual’s unique metrics and biometric data.

Motivating people to adopt a healthier lifestyle through smart forms of encouragement.

There are plenty of fitness apps for mobile devices that help you train and exercise on your own, based on video and audio instructions. But unlike a human personal trainer, such apps don’t tell you when you risk hurting your back doing heavy squats, or when your down dog is way too crooked. A number of companies are now experimenting with wearable technology in this regard, i.e. the use of built-in sensors to guide the user and provide feedback. The aim is to ensure that we don’t just exercise – but that we exercise in the right way.

Alas, personal trainers could soon join journalists and other professionals who have reason to worry about being replaced by an AI in the near future.

Nevertheless, there are still many things that smartwatches are far from mastering. The area of nutrition and diet, for example, is far more complex than simply measuring physical activity.

Perhaps the pedometer is the vote compass of wearable technology? In other words, the only digital service we really need.

Perhaps the pedometer is the vote compass of wearable technology? In other words, the only digital service we really need.

Nutrition research is sometimes subject to criticism for methodological issues. For practical reasons, scientists are constrained to execute observational studies and to rely on people’s own information regarding their dietary habits. The problem, of course, is that people – whether due to forgetfulness or embellishment – don’t always do what they say they do.

The problem, of course, is that people – whether due to forgetfulness or embellishment – don’t always do what they say they do.

And it is difficult to distinguish between cause and effect in these types of studies – or what is simply genetics, rather than habits.

An increasing amount of research also suggests that how we are affected by our diet is highly individual (which explains why individuals who have achieved success with a certain diet – be it low-carb, intermittent fasting or something else – are so eager to tell the world). There quite simply isn’t one diet that suits everyone.

AI has enormous potential

Here, artificial intelligence could have enormous potential when it comes to cracking the individual code. Exactly how should I, out of all billions of people, eat in order to be healthy? But more advanced measurement methods are also required. Blood sugar meters will be a key component. Google, among others, has conducted research into contact lenses that can measure the glucose level in tears.

If we adopt a full-blown science fiction perspective, Apple Watch and the likes from Samsung, Fitbit and other manufacturers are probably just one step on the path to a future reality in which we have a chip implanted directly into our body, or nanobots injected into our bloodstream.

But enough for now about the technological developments – what are the human drivers behind this accelerating monitoring of ourselves?

Perhaps it’s not really all that remarkable. All high-performing, self-absorbed people have simply been presented with yet another way to measure their success in life. Society’s constant pressure to perform, literally strapped around your wrist.

Extremely frustrated

Most smartwatches are pretty good at detecting when you consciously or unconsciously engage in some form of physical activity, such as walking or cycling. They discreetly buzz to suggest that they should start monitoring your current training session. I myself get extremely frustrated when I have commenced a walk or gym workout and realise that I have forgotten to put on my watch. If the exercise isn’t registered then it hasn’t happened!

The most amusing experience occurred a few years ago when I was taking my two children to preschool, and the Samsung watch I was wearing at the time asked me if I was engaged in high-intensity interval training.

Nowadays, as soon as there is a trend change in my physical performance, I receive a notification from my Apple Watch: I have exercised 27% more this month than last, my recovery heart rate has improved by 14% compared to the same period last year, and so on.

By gathering more and more data, we obtain an increasingly better basis for making decisions about our health – or having such decisions made for us. Inevitably, the smartwatch seems destined to become a personal 24-hour health employee.

When McKinsey recently published a special report on the wellness industry, it was valued at 1.5 trillion USD, with an annual growth rate of 5–10%. The consulting firm provides quite a good summary of all aspects covered by the term “wellness” from a consumer perspective:

- Health

- Fitness

- Nutrition

- Appearance

- Sleep

- Mindfulness

Wearable technology has potential in more or less all of these fields. Are we dealing with a toxic cocktail, with our own high expectations of ourselves, fuelled by a growing wellness industry and technological developments – soon on AI steroids – that perhaps is not particularly health-promoting at all?

Recently, in the course of my professional duties, I carried out a test of various yoga apps. One particularly nasty app had, when notifications were activated, opinions on most aspects of my life. When, for the fifth time that day, completely out of the blue, it asked me if I had remembered to drink a glass of water or recommended a playlist of soothing sounds, my response was not to respectfully mumble “Namaste.”

A relentless PT is perhaps possible to endure during three 60-minute sessions a week. But if he, completely unsolicited, were to tap me on the wrist with admonitions any time of the day, every day of the week, I’m fairly sure that I would terminate our arrangement pretty quickly.

What happens when everything is to be optimised, even such basic needs as sleeping and eating?

What happens when everything is to be optimised, even such basic needs as sleeping and eating? If there is something that should be allowed to be immeasurable – and permitted to be highly subjective – perhaps it is our own well-being. The constant process of evaluation can in itself lead to stress and pressure. When our health is measured down to each breath, it is simply not that… healthy anymore.

The philosopher Jonna Bornemark made quite an impact in the Swedish debate a few years ago with the book “The Renaissance of the Immeasurable.”

A showdown with the age of measurability, with a broadside aimed at New Public Management. When public services are standardised and everything must be documented to the point of absurdity, feelings – and the ability to act on them – are eventually rationalised away.

A philosophical book achieving such success was a little unexpected, but the protest says something about the times in which we now live. And her arguments are just as valid when it comes to the measurement of our personal performance.

If you’d like, it is also possible to add a class perspective to this dystopia. There is a correlation between socioeconomic factors and health. If advanced technology becomes an important component of well-being, this will benefit groups that have access to such technology. While those with less education and lower income – whose health status is already impacted to a greater degree by a sedentary lifestyle and poor diet – will fall even further behind.

So, please allow me to offer an alternative future scenario to the one in which large parts of the population will be walking around with a screaming health fascist around their wrist.

An ugly plastic device

Do you remember the electronic pedometers that were around long before smartphones and smartwatches ever existed? A rather ugly plastic device that you attached to your belt so that you could proudly announce to your colleagues how many steps you had taken during the day.

All right, here comes a perhaps slightly far-fetched analogy, but keep in mind that you are dealing with a former political news editor who has now switched to fitness journalism, so please bear with me.

During all my years covering politics, we tried to come up with a new, innovative digital service prior to each general election. Despite the best efforts of skilled developers and creative reporters during countless workshops every four years, nothing we created has ever come close to sparking our readers’ interest in the same way as The Vote Compass (“Valkompassen” in Sweden, “Valgomat” in Norway). You know, the digital form that asks you to answer 25 policy-related questions and then indicates which political party best matches your own views.

An ingenious idea – which was launched on SvD.se (as the first Swedish news site!) as early as 1998.

The most important question

How has this success from the early days of digitalisation been able to remain so unthreatened for almost three decades? Probably because it answers the most important question the reader asks herself during an election campaign: “Who should I vote for?” (The second most important question – “Who will win the election?” – is answered by opinion polls.)

Perhaps the pedometer is the vote compass of wearable technology? In other words, the only digital service we really need.

It has now moved into our mobile phones and smartwatches, but it likely still remains the most common way of using wearable technology for health purposes. Am I going to reach my goal of 10,000 steps a day or not? (According to the latest research, a lot less is actually required to achieve health benefits.) Perhaps most of us don’t want to know more.

To me, the heart rate monitor is the only wearable function I actually find useful in my personal health project, to make sure I remain in the right heart rate zone during my workout. Slightly more advanced than counting steps, but not much.

My point is that technology will not be used just because it exists and is advanced. Rather, the technology that succeeds is the technology that meets actual needs in our daily lives (or that manages to manipulate our psychological needs, like social media).

I propose that all developers of wearable technology should apply my “mother test:” Is this something that would interest a self-absorbed person? Or, to use somewhat more correct customer insights language: Is this helpful for people in their daily lives?

When I received what, at the time, was the brand new Apple Watch model from my husband last Christmas, I initially experienced childlike delight at exploring all the exciting functions. The new sleep tracker was particularly alluring.

By sleeping with the watch on (when are you actually supposed to charge it?), each morning I could take part in a series of neat diagrams to see how I had moved between REM sleep, core sleep, deep sleep and wakefulness during the night. And, not least, if I had reached the goal of sleeping for a total of eight hours, as you should if you want to be at the top of your game.

But after a month or so I started taking the watch off at night.

The feeling of constantly being monitored and evaluated did not contribute to my night rest.

And the irony of the fact that even recovery had become a measurable performance was something that could not be missed – not even by a self-absorbed SvD editor.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Tobias Brandel

Science Editor, SvD

Years in Schibsted: 20

My favourite song the last decade: Chandelier – Sia

Will climate change reset capitalism?

Will climate change reset capitalism?

A miracle that created unprecedented prosperity or a system programmed to eradicate mankind? Never before has modern capitalism been as controversial as it has been in the early 2020s. But what would version 4.0 of a capitalist system look like?

By Andreas Cervenka

Will climate change reset capitalism?

A miracle that created unprecedented prosperity or a system programmed to eradicate mankind? Never before has modern capitalism been as controversial as it has been in the early 2020s. But what would version 4.0 of a capitalist system look like?

By Andreas Cervenka

If the dilemma faced by mankind were to be summarised in just a few figures, these would make a good start. First: 16.82. That’s how many degrees Celsius the global-mean surface air temperature rose to in August 2023; the highest ever registered and around 1.5 degrees higher than the pre-industrial period (1850-1900).

Next: 2,500 billion. That’s how many Swedish Krona the world’s five biggest oil companies made in profits in 2022, which was double that of the previous year. Investments in new extractions of oil and gas in 2023 are predicted to approach 6,000 billion SEK the highest figure since 2015, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Ramping up production

In the pursuit of bigger profits, the oil and gas majors are ramping up production rather than investing in renewable energy sources that are known to be less profitable. By the standards of modern capitalism, the oil majors’ advances make an amazing success story.

The ExxonMobil share price has risen by 250% since the autumn of 2020, and in September 2023 it reached an all-time high. ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods’ compensation rose from 175 million SEK in 2020 to over 400 million SEK in 2022. The shares he received as a bonus during his six years as CEO are now worth 1.8 billion SEK in total. The signal the system is sending to Darren Woods and others in similar positions is: keep up the good work! So expect production and sales of fossil fuels to continue to increase.

The problem of course is that ExxonMobil’s income statement and share price only tell one side of the story. At the same time as this hyper-effective profit-making machine enriches shareholders, it’s also indirectly generating waste in the form of huge costs, both human and economic.

In 2022, the world’s five biggest oil companies made 2,500 billion Swedish Krona in profits.

In 2022, the world’s five biggest oil companies made 2,500 billion Swedish Krona in profits.

The extreme weather events of 2023 make the looming climate catastrophe caused by rising CO2 emissions – which researchers have long been warning us about – seem less like a distant dystopia and more like an acute situation in the here and now. And ExxonMobil’s share of the bill for the costs is precisely zero. The profits flow to the company’s owners while the costs are incurred by current and future generations of people.

Ultimately, this inherent conflict can be seen as a question of priorities: what’s more important – profit or the survival of humanity? For more than 50 years now, the answer has been obvious: profit!

What’s more important – profit or the survival of humanity? For more than 50 years now, the answer has been obvious: profit!

In recent years, however, many have started to question the fairness of this choice for what seems to be good reasons. To understand where capitalism stands today and where it is heading, we need to rewind the tape.

There are two key years to keep in mind, the first of which is 1970. That was when an essay written by the American economist Milton Friedman was published in New York Times Magazine. The 18,000-characters-long essay exudes a sense of frustration. Friedman questioned the prevailing doctrine at the time of the need for businesses to exercise social responsibility.

A global revolution

He dismissed it as nonsense, making his view clear in the essay title: “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” It would mark the start of a global revolution in the business world. The singular purpose of a business was to enrich its owners. Shareholder capitalism was born.

In its statement on the purpose of a corporation, the powerful Business Roundtable, an association of the leading companies in the United States, declared that corporations existed to serve their owners. The new dogma was personified by the legendary Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric between 1980 and 2001. His business principles included continuous restructuring processes, relocation of production to low-wage countries, and a crass staff policy of firing the bottom 10% of employees deemed to be low performers every year.

In recent years many have started to question the fairness of the fact that profit is the overall goal.

In recent years many have started to question the fairness of the fact that profit is the overall goal.

The core of this new doctrine is perhaps best captured in the character of Gordon Gekko, played by Michael Douglas in the film Wall Street from 1987. “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.” The film’s director Oliver Stone thought that the film would serve as a warning to the upcoming generation. Instead, it became arguably the most successful recruitment campaign ever for the finance industry. Everyone wanted to be like Gordon Gekko and Jack Welch, who in 1999 was hailed by Fortune as “CEO of the Century.”

To get to the next key year, we need to fast forward 49 years to 2019, the year when the Business Roundtable adopted a new version of its statement on the purpose of a corporation. This one contained a dramatic change: the wording about shareholder value was now replaced by a statement about how the company would benefit all stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders. The new statement was signed by 181 business leaders, including Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Apple’s Tim Cook.

A model under strain

Later the same year, the Financial Times, the favoured newspaper of the global financial industry, launched a large-scale campaign called “Capitalism: time for a reset.” The editor at the time, Lionel Barber, wrote: “The liberal capitalist model has delivered peace, prosperity and technological progress for the past 50 years, dramatically reducing poverty and raising living standards around the world. But in the decade since the global financial crisis, the model has come under strain, particularly the focus on maximising profit and shareholder value. These principles of good business are necessary but not sufficient. It’s time for a reset.”

This marked an extraordinary U-turn. What had happened? According to the reputable business newspaper The Economist, the answer was simple: Karl Marx was right.

According to the reputable business newspaper The Economist, the answer was simple: Karl Marx was right.

In an analysis performed back in 2018, the newspaper concluded that many of the renowned philosopher’s predictions about capitalism had actually come true. According to Marx, capitalism is in essence a system of rent-seeking whereby a few can accrue vast profits at others’ expense without contributing to society. He also believed that capitalism tended to create monopolies, that it would inevitably reach the far corners of the world and that workers would be the losers through being forced to move from one insecure job to the next.

Half of the companies in the 2003 ranking of the world’s top ten companies – Apple, Google, Amazon, Nvidia and Meta – hold monopolistic positions in their respective markets. The tech giants’ dominance has been compared to that of America’s so-called robber barons of the late 19th century. The gig economy has created an army of workers in a weak negotiating position.

The share of value created in companies that goes to the employees has steadily declined in the Western world since the 1970s. According to the International Monetary Fund, a major contributory factor to the high rate of inflation in the past two years is that companies took the opportunity to increase their profits.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and impact investing are concepts that have been established in recent years.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and impact investing are concepts that have been established in recent years.

Another side effect that has been linked to the shareholder paradigm is increased inequality. In 1970, the CEO of a large US company earned the equivalent of 24 workers; by 2021 this figure had risen to 399. Whereas wages for ordinary people rose in the post-war decades, over the past 15 years they have stagnated, but for those at the top they have risen. Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf has called the system that enriches the few rather than the many “rigged capitalism.”