Ten years of spotting trends

Ten years of spotting trends

What happened with the trends we have written about during the years? Have the Schibsted Future Report been able to foresee where they went? For ten years now we have produced the report – we celebrate this with looking back and reflecting over the changes we’ve seen.

Ten years of spotting trends

What happened with the trends we have written about during the years? Have the Schibsted Future Report been able to foresee where they went? For ten years now we have produced the report – we celebrate this with looking back and reflecting over the changes we’ve seen.

Serendipity opens up your mind

Do you recognise the feeling of not knowing where an idea came from? Suddenly it was just there, perhaps because you let your mind wander in unplanned…

A decade of visions – and a few failures

Eternal life, the metaverse, Google glasses: they came, they saw, but did they conquer? For the past ten years, the Schibsted Future Report has pried open the…

Favourite songs from the last decade

In this tenth edition of the Future Report all authors have chosen their favourite songfrom the last decade. Listen to them all on Spotify.

10 years in pictures

Which are the most memorable and best pictures from the last decade? As Future Report celebrates its tenth anniversary we have looked back and gathered…

Serendipity opens up your mind

Serendipity opens up your mind

This 2024 edition of the Schibsted Future Report is the tenth. Upon reflecting on the past reports, one article stands out as unexpectedly relevant today for editor Ann Axelsson. It celebrates the imagination and creativity that comes from unexpected encounters. In this tenth report we also look back at some of the trends we have looked into during the years – read more here.

By Ann Axelsson

Serendipity opens up your mind

This 2024 edition of the Schibsted Future Report is the tenth. Upon reflecting on the past reports, one article stands out as unexpectedly relevant today for editor Ann Axelsson. It celebrates the imagination and creativity that comes from unexpected encounters.

In this tenth report we also look back at some of the trends we have looked into during the years – read more here.

By Ann Axelsson

Do you recognise the feeling of not knowing where an idea came from? Suddenly it was just there, perhaps because you let your mind wander in unplanned directions. Or sometimes a name you didn’t know you remembered simply pops into your head. Our brains truly work in mysterious ways. Our brain is also the inspiration for the AI technology we have today.

For the past ten years, we have produced the Schibsted Future Report. From the very beginning, AI was an important theme, and over the years, we have dived deep into the technology behind it – as we also do now. But when I started to reflect on all the reports we’ve produced, one article came to mind as being unexpectedly relevant in our discussions about technology and what it means to us as humans and society.

The risks of filter bubbles

It’s a story written for the 2016 report by Professor R. Ravi, who was involved in setting up a digital competence program for Schibsted. The title is “Serendipity – in search of the human algorithm,” and it’s about the risks associated with filter bubbles. But as I now reflect, it’s the very concept of serendipity that has stuck with me – and the benefits of serendipity that often lead to creativity and new ideas. The concept of serendipity comes from a Persian fairy tale about the three princes of Serendip, who were always making unexpected discoveries of things that they weren’t necessarily searching for. Professor Ravi describes the benefits of serendipity in his article like this:

“Letting one’s attention wander is an important precondition for free association and discovery via synthesis of ideas from various unrelated domains. Indeed, bright flashes of creativity are often preceded by such wanderings among seemingly unrelated concepts.”

Perhaps this ability is the biggest differentiator between us humans and AI applications, however advanced they are. And what will happen if we let go of that and lean too much on machines and the existing data from which they learn?

With that in mind, it’s no coincidence that the illustrations that accompany the AI articles in this report are not made with the help of AI. They are made by a human hand. Our photo editor Emma- Sofia has printed and cut out photos to create paper figures, put them on sticks, and placed them on a scene made of cardboard. An idea we came up with after a visit to the Museum of Technology in Stockholm. AI has and will continue to make wonders, no doubt. Not least in the media industry. But I believe that it’s important to also remember that human creativity is unique.

AI is like electricity

Over the years we have put different names on the new realities we’ve foreseen.

We have spoken of the synthetic decade, of the Internet of Things, and of the Metaverse. But perhaps the description given in the 2018 report by Azeem Azaar, Schibsted’s VP of Venture & Foresight in Schibsted2016-2017, is the very best. He described AI as electricity, an infrastructure that will power all parts of our daily lives, without us even noticing.

Speaking of serendipity, we have through the years also tried to capture trends that are not only technology-driven but have also caught people’s interest. Like biking into the future, or what a truly sustainable society looks like, or Formula 1. In this tenth edition, we look back on some of the trends we have written about to see if we were right – or wrong. Open this fold-out to find out.

As an editor looking back, there is one obvious reflection about the report itself and about Schibsted. Today, Schibsted is reaching out to people more often as one company in itself. Millions of end-users meet us every day through Schibsted’s login service Schibsted Account. And in the last few years, this report has become an important tool to spread the story of who we are and what we do.

Ten years is a long time, not least when considering the speed of change in technology, society and business. But from other perspectives, it’s not long at all. This year we have asked all contributors to pick their favourite song from the last decade. I was certain which song I wanted to pick – until I realised that that song was about 20 years old.

I hope you enjoy all the songs on our Schibsted Spotify playlist, individually selected by several creative and unique human beings.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Facts

10 issues of Schibsted Future Report have been published.

174 people have contributed with text to the reports.

50,000 is the approximate number of reports distributed.

Ann Axelsson

Senior Product Manager, Strategic Communication, Schibsted

Years in Schibsted: 25

My favourite song the last decade: Paper Doll – John Mayer

A decade of visions – and a few failures

A decade of visions – and a few failures

Eternal life, the metaverse, Google glasses: they came, they saw, but did they conquer? For the past ten years, the Schibsted Future Report has pried open the door to the future. It has seen a decade of visions – and a few failures. We decided to look back at some of the trends we highlighted in the course of those years to see how they turned out.

By Erica Treijs

A decade of visions – and a few failures

Eternal life, the metaverse, Google glasses: they came, they saw, but did they conquer? For the past ten years, the Schibsted Future Report has pried open the door to the future. It has seen a decade of visions – and a few failures. We decided to look back at some of the trends we highlighted in the course of those years to see how they turned out.

By Erica Treijs

Future Report 2018: Biking into the future

Cars and cities make a bad combination. A car takes up a lot of space. On average it stands idle 96% of the time, and when it does move, it’s like a heavy, dangerous, noisy colossus which, if run on fossil fuel, also causes global warming.

For obvious reasons, a bike takes up much less space. And in recent years this 200-year-or-so invention has undergone a metamorphosis. Already in the 2018 edition of the Future Report, we predicted that we would cycle into the future, and we now have modern designed pedal-driven contraptions for every occasion and purpose. Not even cycling uphill with a heavy load has to end in snot and sweat as long as your electric motor kicks in at the first sign of an incline. When it comes to bicycle-friendly cities, Copenhagen is in front position, with lots of spacious and clearly signposted bike lanes.

Cities like Oslo and Stockholm still have some way to go, unfortunately, but that hasn’t impeded the advance of rental bikes or electric scooters, all of them based on access to new technologies, and recent years have seen huge developments in sensors, mobile technology, GPS trackers and artificial intelligence. Everything is paving the way for a new sharing economy, and this is just the beginning.

In the 2018 edition of the Future Report, we predicted that we would cycle into the future, and we now have modern designed pedal-driven contraptions for every occasion and purpose.

In the 2018 edition of the Future Report, we predicted that we would cycle into the future, and we now have modern designed pedal-driven contraptions for every occasion and purpose.

Future Report 2018: How to make friends with robots

Being digitally represented by an avatar is one thing, but having a robot as a friend is something quite different. That was precisely what we predicted would happen within just two years when we published the 2018 edition of the Future Report. A little robot that served you freshly brewed coffee in bed with a smile on its steel-grey lips might not be such a bad idea, but getting the day’s main headlines projected onto the ceiling seemed a little over the top, as did having a robot decide what you should wear.

Still, if a robotic friend were to become a reality in the foreseeable future, what would it look like? Research shows that we tend to think of robots as charming as long as they resemble something non-human, like a bear or a rabbit, but that we flinch the moment we meet robotsthat resemble humans. Perhaps the question shouldn’t be whether or not robots should resemble humans, but rather whether they would come to redefine what it means to be human? What ethical standards and values should your robotic friend have to really be your friend?

We tend to think of robots as charming as long as they resemble something non-human.

We tend to think of robots as charming as long as they resemble something non-human.

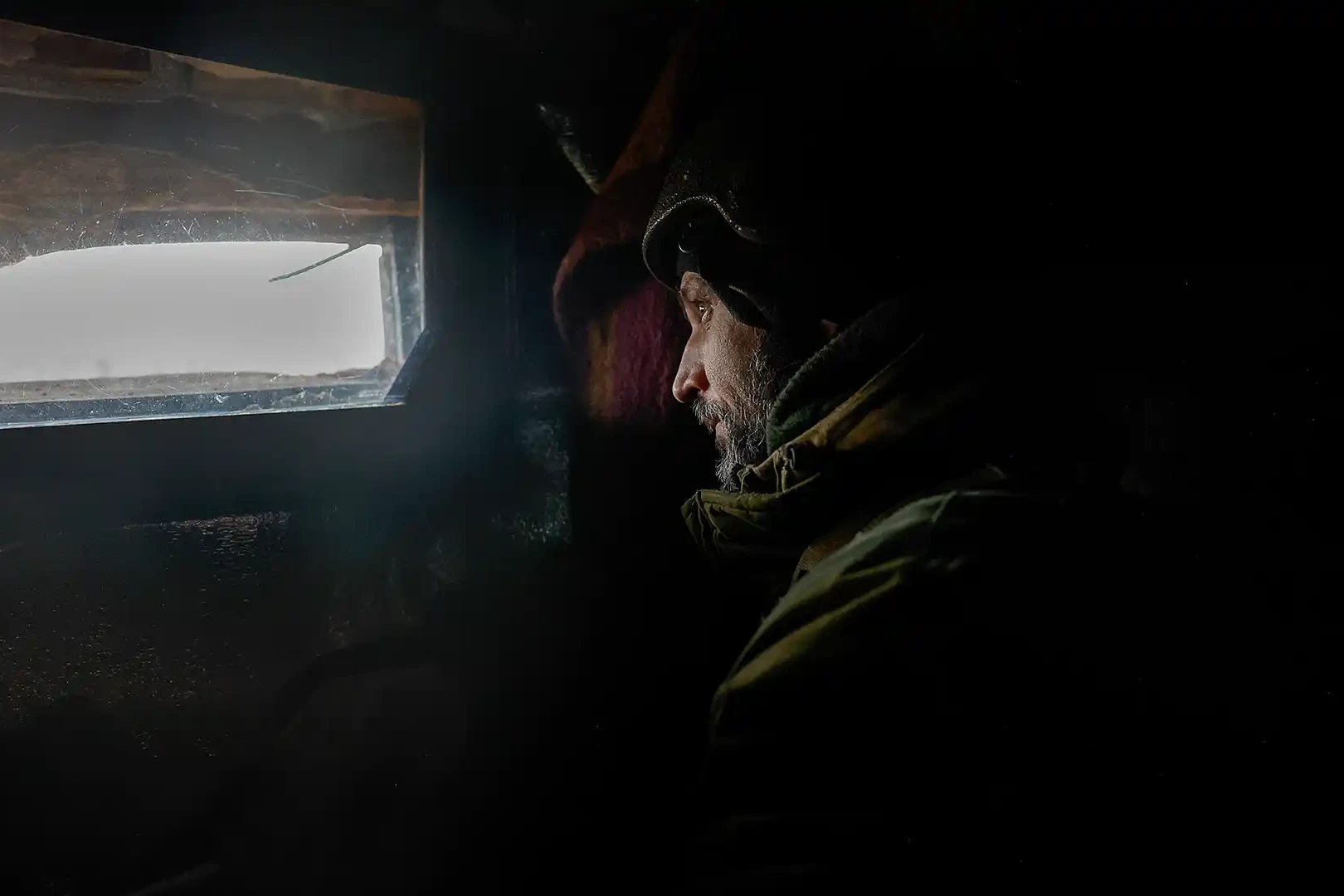

Future Report 2019: A new space age

“Don’t be afraid of the man in the moon,” sang David Bowie in his self-titled debut album, two years before Neil Armstrong took one giant leap for mankind in 1967. And only a month before the Apollo 11 space flight, Bowie sang about Major Tom, and the people on Earth joined in and stared into space. There’s something alluring out there, in the unknown. But maybe it’s like Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins said, that the moon is not a destination; it’s a direction?

In 2019 we wrote about the showdown in space, which no longer is happening between countries but between private entrepreneurs. Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX, believes that when World War III breaks out, civilisation will survive on Mars. Jeff Bezos, Mr Amazon, sees space more as a place to do our dirty work, where mining, manufacturing and recycling will be done as part of a vision to keep Earth “clean.”

And even though we can now travel into space with SpaceX, there’s little talk of colonies on Mars and mining operations. The rockets seem to have ended up in a more mundane sphere as carriers of satellites and space station equipment. And perhaps most importantly, new areas of application here on Earth are often found for innovations that were developed for space technology.

Famous entrepreneurs don’t speak very loudly about the next space age anymore.

Famous entrepreneurs don’t speak very loudly about the next space age anymore.

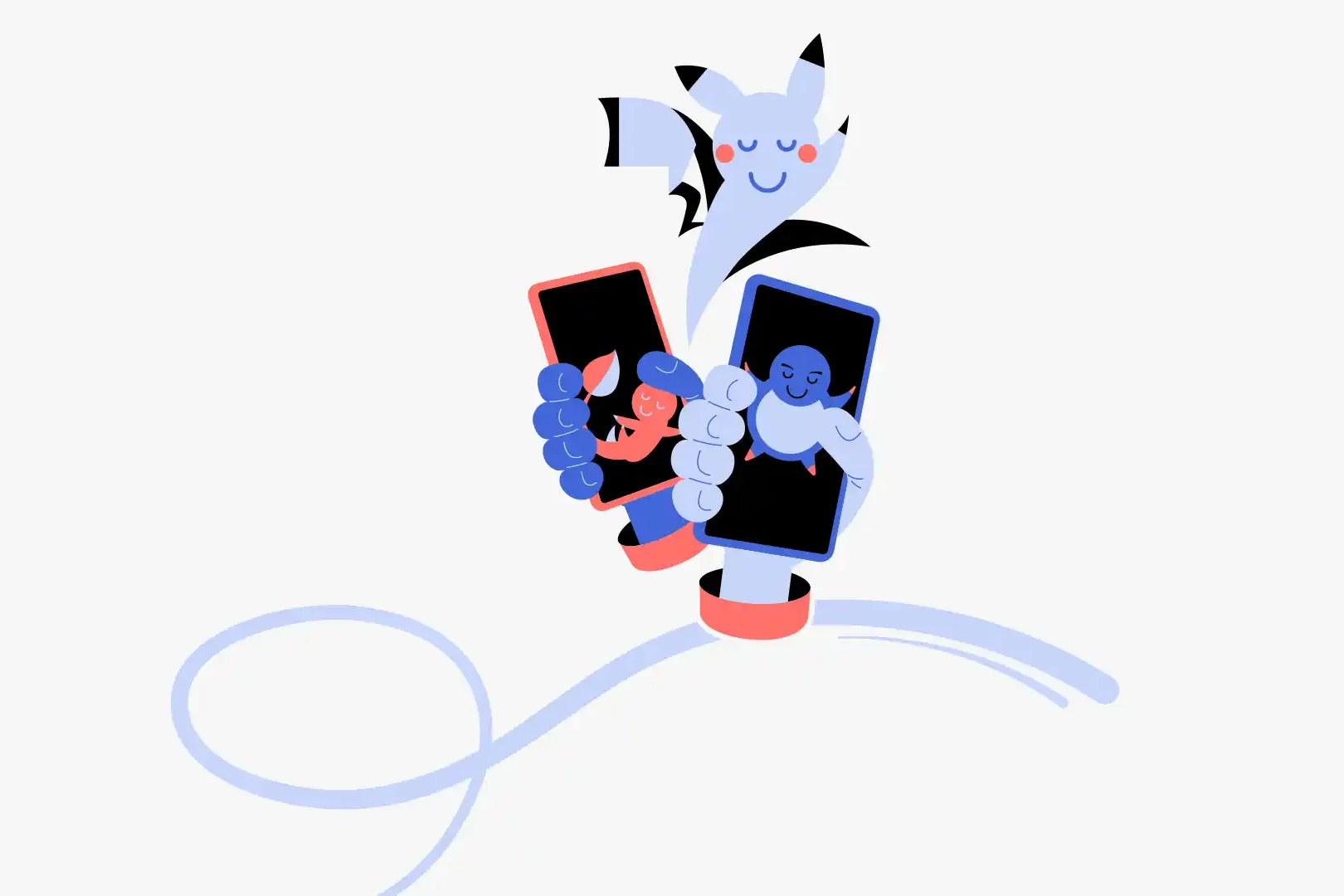

Future Report 2017: Reality is getting hacked

Suddenly we saw them everywhere: people who moved around the city, often in groups, with their phones at the ready. They were out hunting, but not for blood; instead they were frantically searching for some of the 700 figures in the Pokémon Go game. Using mobile phone cameras and geolocations, the game combines virtual and actual reality, and when it was launched it spread like wildfire. For a while, the game had more daily users in the US than Twitter, and users even spent more time on the app than on Facebook. One of the truly unique features of Pokémon Go was that its users not only made imaginary or digital friends; it created communities of people who met and searched for Pokémon both in their own towns and further afield. Of course, the movement had its own “pokestops,” where more commercial actors made a fast buck from the hype. Its huge success in 2017 is unquestionable, so its sudden demise and the fact that no successors pursued the augmented reality track came as a surprise. But the game world is a lucrative hunting ground, with no limits on technological innovation. No one knows what will come next, only that more will come. A lot more.

In 2017 Pokémon Go was a huge success.

In 2017, Pokémon Go was a huge success.

Future Report 2015: The rise of wearables

It had been in the cards for some time. It was 2015, and smart devices were to become wearable accessories and be used in combination with smartphones and tablets. Google Glass was essentially a brand of glasses that could communicate through audio, record video and show information via the tiny display above the eye. This new gadget was clearly going to fundamentally change everything. But there was a catch, namely human vanity – and possibly the USD 1,500 price tag.

Aside from being hideously ugly, heads-up/hands-free technologies demanded way too much attention. To be able to put down your phone and shut off the computer is, after all, something that allows human behaviour other than that based on ones and zeros. Google Glass disappeared from the shelves in 2015 but wasn’t sent to the graveyard until 2023. But – now Apple is soon entering the scene. Their Vision Pro is said to be the future of AR/VR experience. More for indoor gaming than city cruising though.

Wearables that demand too much attention is a challenge.

Wearables that demand too much attention is a challenge.

Future Report 2017: Cars reinventing urban life

Electric vehicles have now become part of the urban landscape, with cables all over the place, and chargepoints sprouting up on streets and in car parks and residential parking facilities. Electrification is going more or less as the politicians planned; the EV fleet is growing and the charging infrastructure is gradually expanding. But what’s next?

Autonomous vehicles, many would say, and back in 2017 we predicted their rapid development. The technology now exists, for sure, but there are still no real answers to the ethical and/or moral issues. Who or what is at fault when an accident occurs? The technology is being tested in many places, with good results when it comes to aspects like accessibility and energy consumption. Put simply, it is progressing but, as is often the case, not as fast as expected.

On 16 August 2016, Ford Motor Company announced its intention to offer on-demand autonomous vehicles in 2021. By the time 2024 comes around, these driverless vehicles will still not be running on European roads and fundamentally changing the entire transport sector. No one knows when it will happen, but we know that it can. Just look at how electric vehicles entered the market.

There are still issues to solve for autonomous vehicles.

There are still issues to solve for autonomous vehicles.

Future Report 2019: Hacking the code of ageing

“If you could choose between eternal life and having children, which would you choose?” A rhetorical question that effectively drives the point home. Not even in Silicon Valley can immortality be bought – yet. But the idea that it might be possible to prolong human life has for some become an obsession and for others a business concept, and it’s a trend that has grown since 2019.

What is immortality, anyway? Is it a matter of charging your brain in the cloud, or does it take cryonics, preserving human bodies at ultra-low temperatures in the hope that they can one day be revived? Well, research is already being done on how a body can get rid of ageing “zombie cells,” on the human anti-ageing pill NAD+ and on injections of stem cells, all with the aim of prolonging human life.

More attention and funding are needed if researchers are to fully investigate the limits to human health and life expectancy. And those who think that manipulating the course of nature is unnatural should also ask themselves whether it isn’t human behaviour to push our boundaries. Only time will tell.

The interest for eternal life is growing.

The interest for eternal life is growing.

Future Report 2023: Redefining our digital lives

Few subjects in the world of technology have prompted such unbridled optimism and contemptuous scepticism as “the metaverse,” the next chapter for the internet. A difficult to define successor to today’s internet, though in a 3D universe. The concept itself, championed primarily by Meta, has almost disappeared from the agenda, in step with the company’s cutbacks.

But regardless of what we call it, there are two things we know: as the boundaries between the digital and the physical are increasingly blurred, we will use more of our bodies and our senses to integrate with computers, just as computers will become increasingly embedded in our everyday lives. Our digital lives will become more social, and it will be harder to differentiate between a game, a concert and a social network. Read more: The editor’s reflections on the tenth anniversary

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Erica Treijs

Reporter at Svenska Dagbladet

Years in Schibsted: 23

My favourite song: Chronically Cautious – Hello – Adele

Machines like us - a brief history of artificial intelligence

Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

“AI is a bigger threat than climate change”, “AI could cause ‘civilisation destruction’”, “Humanity is failing the new technology’s challenge.”

As OpenAI launched ChatGPT in 2022, not only did people envision amazing new ways to use the technology for the good of humanity, but many AI scientists expressed grave concern that the technology would be used to flood the internet with disinformation or worse, that machine intelligence was about to surpass human intelligence, presenting questions we are not yet ready to answer.

Many have speculated that low-level jobs will soon be taken over by AI. But no longer are only simple, repetitive occupations at risk. Lawyers, physicians, artists, writers… as artificial intelligence approaches the human level we all should worry about – or look forward to – machines replacing us in the workplace.

I recently spoke to Max Tegmark about these developments. He is the author of “Life 3.0,” a professor at MIT and a renowned AI expert, and he is profoundly worried. Tegmark has been campaigning against nuclear weapons for years, but at present, he considers artificial intelligence an even greater existential risk. If we choose to replace ourselves, and let machines do all our work for us, the human species may simply lose the desire to carry on and to procreate. But why, Tegmark wonders, would we want to replace ourselves with machines?

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

In fact, this question echoes through the ages: Why have scientists and alchemists for so long strived to create not just useful machines, but machines like us?

The pursuit of artificial intelligence is not about merely making efficient tools, like calculators and word processors. It is about mimicking human intelligence, a quest to equal or even surpass it. In essence, turning the myth of creation on its head, making humans the creators of new life through intelligent design. This dream has ancient roots.

An awesome bronze giant

The Greeks told of the divine smith, Hephaestus, who forged automatons to serve its masters. Talos is the most famous of his creations, an awesome bronze giant who patrolled the island of Crete, protecting it against pirates. At Alexandria, the Egyptian scholar Heron built a spectacular array of automata for the theatre. Not intelligent, naturally, but appearing alive.

Around the thirteenth century and onward, many learned men, scholars and occultists were rumoured to possess mystical contraptions known as “brazen heads,” mechanical heads covered in bronze, which could answer any questions put to them. This may have been a legend borne out of the ignorance and jealousy of their scholarly wisdom. No evidence of any scientist or magician creating such a device exists. But soon automatons of a less supernatural kind became all the rage among the European aristocracy.

These cleverly constructed machines were no more than mechanical divertissements made of cogwheels and springs, inspiring awe and wonder. Magic tricks, to entertain guests, rather than actual dark arts. But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

Indeed, in the sixteenth century, the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus claimed to have created a living, breathing homunculus by burying human sperm in horse manure for 40 days, magnetizing it, and then feeding it human blood for 40 more weeks. This little humanoid was said to work as an assistant to its master. Paracelsus promised, in words that could very well refer to the creation of artificial general intelligence far in the future:

“We shall be like gods. We shall duplicate God’s greatest miracle – the creation of man.”

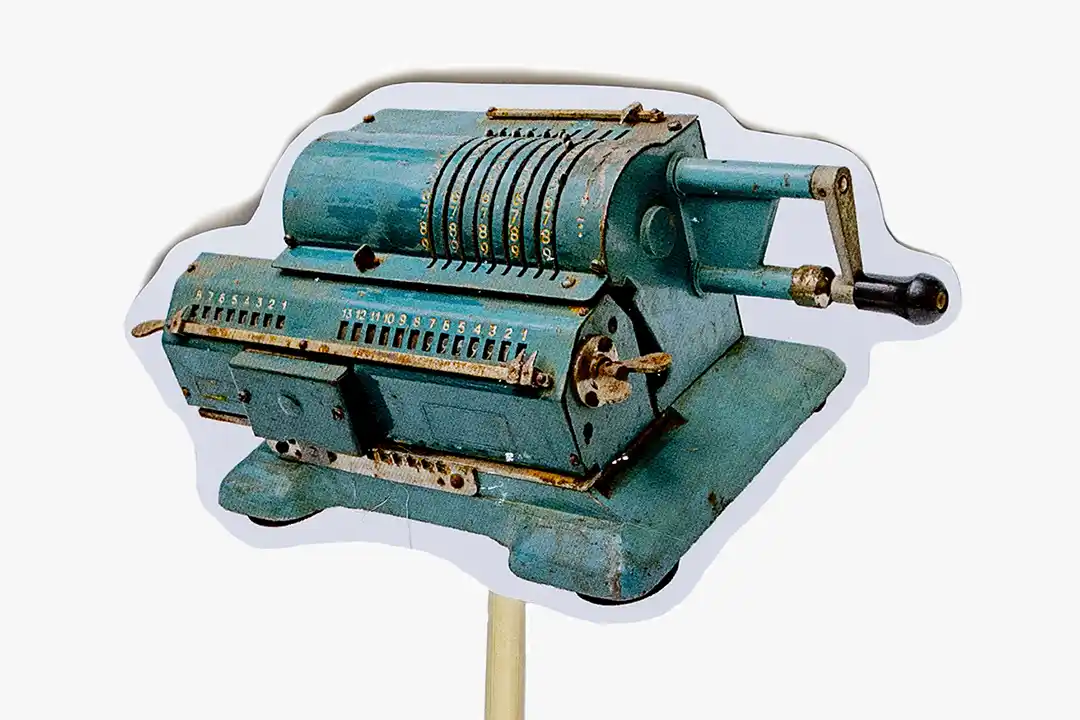

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

In 1818, a sensational horror novel was released that tickled the imagination of thousands of readers. “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley, is the tale of a modern scientist following in the footsteps of alchemists like Paracelsus, consumed by the idea of creating an artificial man through scientific means. The Italian biologist Luigi Galvani had recently discovered that electricity is the means by which the brain sends signals to the muscles, so Shelley had Viktor Frankenstein animating his creature by electric current from a burst of lightning. The result, of course, is Frankenstein’s monster – a huge man, terrifying to its creator and woefully unhappy, who goes on a murderous rampage. The tale may serve as a warning of humankind’s troubles in controlling their greatest inventions.

Starting point of modern computing

Many historians would cite Charles Babbage’s designs for the Analytical Engine as the starting point of modern computing. In the 1830s, Babbage, a British inventor, engineer and mathematician, came up with two designs for machines capable of performing mathematical calculations. The first, called the Difference Engine, was funded by the British government and Babbage himself, but the project was never completed.

The second, called the Analytical Engine, was even more ambitious, and funding was hard to come by. Along with his companion Lady Ada Lovelace, he came up with different schemes to fund the project. At one point they proposed a tic-tac-toe-playing machine to entice investors, then they considered building a chess machine. Before they could build it, however, they came up with an even better idea. They would build the perfect system for betting on horse races, to fund the completion of the Engine. The scheme was meticulously planned by some of the brightest minds in England and ended in spectacular failure. Soon Lady Lovelace was deep in debt and rescued not by any ingenious machines but by her kind mother.

The Analytical Engine, like its predecessor, was never completed. But Babbage’s designs, along with Lady Lovelace’s ruminations on how the Engine would in theory be able to not only calculate numbers but to have those numbers to represent anything – for instance sounds in a musical composition – was an important step in the creation of the universal computer.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

It would be another century before such a computer was finally realised. The world’s first programmable computer was built in the late 1930s by the German engineer Konrad Zuse. He called the mechanical, motor-driven machine the Z1. Although it was the first computer to be finished, many other engineers were tinkering with computers around the world. At this time, the field of psychology was also starting to understand the human mind as a biological network, and piece by piece figure out its workings. Perhaps the brain was best understood as a machine? And if so, might not a machine such as the computer, in the future, be able to perform the same work as the brain?

With these questions in mind, scientists were again starting to entertain ideas about thinking machines, mimicking human thought and behaviour. Their ideas were collected under names such as “cybernetics,” “automata theory” and “complex information processing”. It was not until 1956 that the American scientist John McCarthy came up with a new name for the field, that proved to be sticky: “artificial intelligence.” That summer he joined 19 other prominent academics at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire for a workshop brainstorming about the exciting new field.

Creating a computer mind

The participants of the conference were engineers, psychologists, neuroscientists, mathematicians, physicists and cognitive scientists; an interdisciplinary brain trust well suited to taking on the challenges of creating a computer mind. Their mission statement – brimming with the naïveté that comes from not yet having tried and failed – outlines their lofty ambitions:

“Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans and improve themselves.”

The participants were confident that they would make great strides in this direction during the two-month workshop. It would be a stretch to say that they achieved their goal, but during those long discussions at the Dartmouth Math Department, they at least firmly established the new field of AI.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Human-level machine intelligence would turn out to be far harder to achieve than the early pioneers imagined. During the following decades, AI hype would be followed by AI winter in a cyclical pattern. Several prominent AI researchers, among them Marvin Minsky, had predicted human-like intelligence by the 1980s. When those predictions were proven wrong, some were deflated, but the Japanese government was eager to have Japan take the lead. In 1981, Japan initiated the Fifth Generation Computing Project, pouring 850 billion dollars into AI research, with the stated goal of creating machines that could carry on conversations, translate languages, interpret pictures and reason like human beings.

Progress was made during this time, primarily with limited systems tuned to play chess or give expert advice in narrow fields of inquiry. But anything even vaguely resembling the dynamic and wide-ranging intelligence of humans remained out of grasp. After the Fifth Generation Project came to an end, without fulfilling its promise, the field again found itself at a low point late in the 1990s.

Luckily, an offshoot of AI research was about to gain new traction. In parallel to the mainstream research going on at prestigious universities, well-funded government programs and hyped-up companies, some scientists had taken an interest in artificial neural networks. The network architecture was thought to resemble the human brain, offering new ways of representing machine thoughts compared to the strictly algorithmic manipulation of symbols of conventional AI systems. A neural network could be trained on appropriate data sets, much like a child learns, until its maze of internal connections becomes suitable for its designated tasks.

A fatal flaw

Artificial neural networks had a fatal flaw, however. As soon as you started to scale a network to do something interesting, its complexity increased exponentially, and the system ground to a halt. The computer hardware of the time, with architecture very different from human brains and far less processing power, simply could not keep up. So, this line of research remained theoretical, dormant for decades until, deep in the 2010s, the time had come for the AI field to enter a new era of machine learning.

Three developments of the new millennium came together to finally make neural networks practical:

Computer hardware kept getting faster, smaller and more energy efficient, as predicted by Moore’s Law.

Computer scientists developed more sophisticated architectures and algorithms for artificial neural networks.

An immense trove of digital text, images and sounds accumulated online, an all-you-can-eat buffet of information for neural networks to be trained on.

Looking back at what was then envisioned, artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name.

With the recent work of DeepMind, OpenAI, Google and Microsoft, we arrive at today’s state of the art. Artificial intelligence may have missed the deadline of Japan’s Fifth Generation Project, but looking back at what was then envisioned – or indeed, what the Dartmouth Workshop sought to achieve – artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name. ChatGPT and its rivals can easily hold conversations with humans; Google Translate and its ilk can translate text and speech in the blink of an eye; and many neural networks not only interpret images but also create beautiful pictures from natural-language prompts.

Several fundamental questions do remain, however. Can these machines truly reason? Can they think? Can they feel? Will they ever?

The French seventeenth-century philosopher René Descartes famously formulated a dualist theory where mind and body are metaphysically separate. He was inspired by the automatons on display in Paris at the time and concluded that mind and body must be different substances. The latter can be replicated by automatons, while the former is singular to man and intimately tied to what makes us us. We think, therefore we are.

Unexpected leaps

With AI science advancing – at times inching forward incrementally, sometimes striding with unexpected leaps – software engineers are getting closer to imitating the human mind as well. Chat GPT has repeatedly defeated the Turing test, designed by the British computer pioneer Alan Turing to settle the question: “Can machines think?”

Refined algorithms, humongous data sets and clever reinforcement learning techniques are pounding at the walls of dualism. Perhaps, as the Dartmouth Workshop proposed, the human mind is a mere machine after all. And if this is the case, why would we not be able to replace it with more efficient machines?

The history of artificial intelligence is a tale of scientific progress, of engineering failures and of triumphs. But it is also the story of our struggle to understand our own minds. Are we truly unique? Are our brains, like our bodies, simply machines governed by electrical impulses? When we dismiss the “thinking” of large language models as simply a series of predictions of what comes next, are we absolutely certain that this does not also apply to human minds?

It seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already.

At this point (as at every point in the history of AI) it seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already. There is still some disagreement about whether we can create feeling machines, however. Conscious machines. Machines that can do and experience everything that a human can and more.

Some aspects of this may be harder than we can foresee. On the other hand, it may be within our power sooner than we think, emerging incidentally as our models become increasingly complex, combining techniques from neural networks with symbolical AI.

Mary Shelley would be delighted to see modern scientists still hard at work trying to realise the ancient dream of godlike creation. The full original title of her famous horror novel is “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.” The subtitle alludes to the crafty Titan from Greek mythology who stole fire from the Olympian gods and gave it to man. Fire, in this old tale, symbolises knowledge, invention and technology – powers Zeus had determined must be reserved for gods and withheld from humankind.

In some versions of the myth, Prometheus gives us more than fire; moulding the human race from clay, he also gives us life. Millennia later, the fire he gave us is still burning bright, and we are now the ones doing the moulding. Not from clay, but from code.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Sam Sundberg

Freelance writer, Svenska Dagbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Light years – The National

A beginner’s guide to generative AI

A beginner’s guide to generative AI

We’ve all heard of AI, machine learning and ChatGPT. But how does it really work? Here’s a beginner’s guide to the technology behind – and what might come next.

By Sven Størmer Thaulow

A beginner’s guide to generative AI

We’ve all heard of AI, machine learning and ChatGPT. But how does it really work? Here’s a beginner’s guide to the technology behind – and what might come next.

By Sven Størmer Thaulow

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, buzzwords like “AI” or “machine learning” are becoming increasingly common. Even if you’re not entirely sure what they mean, chances are you’ve encountered them in some form or another, perhaps through smartphone assistants like Siri or Alexa or in online customer service chats. However, a subset of AI, known as generative AI, is emerging as a transformative force in the digital world. Here’s a closer look at this technology and its implications for the future.

Unravelling the Mystery of Generative AI

At its core, generative AI is about creation. Much like an artist creates a painting or a writer crafts a story, generative AI can produce new content. But instead of paint or words, its tools are data and algorithms.

Imagine having a conversation with a friend about your favourite books. As you talk, your friend might suggest a new book for you to read based on what you’ve mentioned. Generative AI operates on a similar principle. Feed it with enough conversations about books, and it could suggest or even create a synopsis of a book that doesn’t exist but fits within the parameters of the conversations it’s analysed.

The Magic Behind the Screen

The magic of generative AI lies in its ability to produce content, be it text or images. But how exactly does it do this?

For text, generative AI models are trained on vast databases of written content. They analyse patterns, contexts, and structures within these texts. When given a prompt or starting point, they use this training to predict and generate what comes next. It’s like teaching a child to speak by immersing them in conversations until they start forming their own sentences.

On the image front, things get a bit more complex. Techniques like Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are often employed. Here’s a simplified explanation: imagine two AI systems – one is the artist (generator) and the other is the critic (discriminator). The artist creates a picture, and the critic evaluates it. If the critic can easily tell it’s a generated image and not a real one, the artist tries again. This back-and-forth continues until the artist produces something the critic can’t distinguish from a real image. Through this process, the AI becomes adept at creating realistic images.

Societal Impact and the Media Realm

The proliferation of generative AI doesn’t merely affect technological circles; its ripples will be felt across society. As AI-generated content becomes commonplace, our ability to discern between human-created and AI-created material might blur. This poses profound questions about authenticity, trust and the value of human creativity. For media companies like Schibsted, the implications are vast. On one hand, AI can generate news reports, write articles or even create visual content at a pace unmatched by humans, offering efficiency and cost savings. However, this also brings challenges. How do media houses ensure the credibility of AI-generated content? And as audiences become aware of AI’s role in content creation, how will this shape their trust and engagement with media outlets?

Charting the Evolution of Generative AI

Like all technologies, generative AI wasn’t born overnight. It’s been a product of years of research, improvements and refinements. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the capabilities of generative AI expand. Currently, we’re witnessing AI that can draft articles, compose music and generate artwork. Yet, this is just the beginning. The trajectory suggests

a future in which generative AI can create more complex, interactive, and nuanced content. Think of virtual realities indistinguishable from our own, or digital assistants that not only understand our preferences but can also predict our needs before we articulate them.

The Next Wave of Breakthroughs

Predicting the future is always a gamble, but based on the current momentum, several exciting developments appear on the horizon for generative AI.

- Personalised content: In a world saturated with content, personalisation is becoming paramount. Generative AI could craft experiences tailor-made for individuals. Imagine a movie that adjusts its storyline based on your preferences or a video game that evolves based on your playing style.

- Education revolution: Customised learning isn’t new, but with generative AI, it could reach unprecedented levels. Students might have access to study materials created on the fly, precisely addressing their weak points and reinforcing their strengths.

- Artistic collaboration: While some fear AI might replace human artists, a more optimistic view is a future where artists and AI collaborate. An AI could suggest melodies for a musician or sketch ideas for a painter, enriching the creative process.

In conclusion, generative AI lies at the intersection of art and science, holding the promise of a world where technology enhances creativity, personalisation, and efficiency. At Schibsted we feel we are on the cusp of this new era, and that it’s crucial to approach it with both excitement and caution. We must ensure that as we harness its potential, we also consider the ethical implications of AI shaping our reality.

Using an AI co-pilot: How did I make this article?

This article was a classic task for generative AI as it was a fairly generic piece more describing a well-known domain rather than being a very personal and opinionated article – so I used ChatGPT as a co-writer. I tried out a prompt describing the article I wanted. It became very “chatGPT-ish” – lots of numbered bullets with sentences. So I tried again with a prompt saying I wanted it in “New York Times” style. I got closer. I tried some more prompt variations and also limited it to the number of words. When I had the 80% text I wanted I started rewriting somewhat, cleaning up mistakes and adding some elements. And voila – a pretty decent article was born!

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Sven Størmer Thaulow

EVP Chief Data and Technology Officer, Schibsted

Years in Schibsted: 4

My favourite song the last decade: Thinking of a Place – The War On Drugs

Favourite songs from the last decade

Favourite songs from the last decade

In this tenth edition of the Future Report all authors have chosen their favourite song from the last decade. Listen to them all on Spotify.

Favourite songs from the last decade

In this tenth edition of the Future Report all authors have chosen their favourite song from the last decade. Listen to them all on Spotify.

Kristin Skogen Lund, CEO

My favourite song the last decade: Formidable – Stromae

Sam Sundberg, Freelance writer, Svenska Dagbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Light years – The National

Sven Størmer Thaulow, EVP Chief Data and Technology Officer, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Thinking of a Place – The War On Drugs

Ann Axelsson, Senior Product Manager, Strategic Communication, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Paper Doll – John Mayer

Joacim Lund, Technology commentator, Aftenposten

My favourite song the last decade: Bråtebrann – Kverletak

Christopher Pearsell-Ross, UX designer, Schibsted Futures Lab

My favourite song the last decade: Your Best American Girl – Mitski

Ian Vännman, Strategy Advisor, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: I Don’t live Here Anymore – The War on Drugs

John Einar Sandvand, Senior Communications Manager, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Save Your Tears – The Weeknd

Petra Wikström, Senior Director of Public Policy, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Blinding Lights – The Weeknd

Sylvia Brudeli, Chief Product Officer, Nomono

My favourite song the last decade: Smilet i ditt eget speil – Chris Holsten

Hanna Lindqvist, SVP Technology, Schibsted and SVP Aurora Foundations

My favourite song the last decade: Wake Me Up – Avicii

Deng Wuor Joak, Head of Cyber Security, Distribution Innovation, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Mamma Sa – Jonas Benyoub

Eivind Hjertholm Fiskerud, Project Lead AI, Nextgen Newsrooms

My favourite song the last decade: To Mminutter – Lars Vaular & Röyksopp

Andreas Cervenka, Columnist, Aftonbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Cairo, IL – The Brother Brothers

Karl Hahtovirta, Vice President Subscription Sweden, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Get Lucky – Daft Punk

Moa Gårdh, Product och UX director, Aftonbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Ålen – Amason

Edgeir Aksnes, CEO and co-founder Tibber

My favourite song the last decade: Faded – Alan Walker

Nathalie Kåvin, Head of Corporate Brand, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Stark & Sårbar – Moonica Mac

Camilla Buch, Communication Manager, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Chronically Cautious – Braden Bales

Christine Gelfgren, Marketing Strategist, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Yellow Moon – Amason

Markus Ahlberg, Chief Sustainability Officer, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: How Loud Your Heart Gets – Lucius

Christian Printzell Halvorsen, eCommerce & Distribution, Schibsted

My favourite song the last decade: Gospel (with Eminem) – Dr. Dre

Ricki Rebecka Petrini, Head of Marketing & Communications

My favourite song the last decade: Novacane – Frank Ocean

Adam Svanell, Head of Documentary, SvD

My favourite song the last decade: Mam Yinne Wa – Alogte Oho & His Sounds of Joy

Julie Schoen, Press Manager, DBA

My favourite song the last decade: Stor mand – Tobias Rahim and Andreas Odbjerg

Gard Steiro, Publisher, VG

My favourite song the last decade: I Need Never Get Oold – Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats

Lena K Samuelsson, Founder of Schibsted Future Report

My favourite song the last decade: Shallow – Lady Gaga & Bradley Coop

Molly Grönlund Müller, Community Researcher, IN/LAB

My favourite song the last decade: Step Out – José González

Belenn Rebecka Bekele, Community Researcher, IN/LAB

My favourite song the last decade: Son Shine – Sault

Tobias Brandel, Science Editor, SvD

My favourite song the last decade: Chandelier – Sia

Espen Rasmussen, Photo Editor, VG Stories

My favourite song the last decade: Golden Ticket – Highasakite

Enna Kursukangas, People & Culture Director, Schibsted Nordic Marketplaces

My favourite song the last decade: Cha Cha Cha – Käärijä

Michał Domagalski, Engineering Manager, Schibsted

My favourite song: Downtown – Unto Others

Nina Hermansen, Leadership Developer, Schibsted

My favourite song: Black skinhead – Kanye West

Karen Gonçalves, Global Process Owner – Employee On/Offboarding, Schibsted

My favourite song: Lady – Modjo

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Human happiness must be our common goal

“Human happiness must be our common goal”

She thinks we’re discussing AI on the wrong level. And her vision is that everyone should understand how the technology works. Inga Strümke has become a tech celebrity in Norway, much thanks to her bestselling book, “Maskiner som tenker.”

By Ann Axelsson

“Human happiness must be our common goal”

She thinks we’re discussing AI on the wrong level. And her vision is that everyone should understand how the technology works. Inga Strümke has become a tech celebrity in Norway, much thanks to her bestselling book, “Maskiner som tenker.”

By Ann Axelsson

“If you talk about existential risks and appeal to people’s fears, you will get attention,” she says, referring to the dystopian warnings that AI will replace humans and take all jobs.

“These futuristic scenarios are not constructive, and they make it hard to debate the mechanisms behind the technology. What we really need to discuss is how we can develop today’s AI systems according to legislation, our goals, and our values.”

Inga Strümke is an associate professor in AI at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU. She’s also a particle physicist, a frequent public speaker, and a best-selling author. “Maskiner som tenker” (“Machines that think”) has become a bestseller in all categories in Norway.

She also spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. That was a challenge. Until ChatGPT.

“Unfortunately, it takes bad news to get them to listen.”

As a scientist in the field, she of course welcomes progress, and she explains that the scientist’s mindset is to think about what is possible and then develop that.

“That mindset has given us X-ray, GPS, the theory of relativity. And atom bombs. As a scientist, you never know how your findings will be used. That’s where society needs to step in.”

Inga Strümke has spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. She was also a speaker at Shibsted’s strategy summit in October 2023.

Inga Strümke has spent several years reaching out to Norwegian politicians, trying to get them to take AI issues seriously. She was also a speaker at Shibsted’s strategy summit in October 2023.

And she believes that ChatGPT is a perfect example of how bad things can go when you share “fun” new technology openly, without having had discussions about its implications.

“I believe we have a serious problem when pupils are now thinking, ‘Why should I write a text if there is technology that can do it better?’ How will we now make young people understand that an idea starts with a thought in your head and that you need to grow and communicate that idea to get other people to understand it? And if you can’t do that, then you won’t be able to function in society.”

That might sound just as dystopian as the future scenarios. But her point is that we can and we must take the lead here in the Nordics and in Europe when it comes to discussing the role we want technology to play.

“If we can’t manage to figure out how to use what we develop here, then we will end up using solutions developed by tech giants that we are unable to influence.”

Impact across the society

And these discussions, she says, should involve experts from across the board – politicians, social scientists, economists, legal experts, ethics, apart from technologists – since the impact will be felt across all parts of society.

This is also why she thinks it’s so important that as many of us as possible understand what this is about and how the technology works. The things she explains in her book.

“My dream is that anyone can read it. That a woman past 80 would read it and think, ‘I can understand this if I want to.’ I have this passion to empower people on this subject. To make them see that they can look after their own interests.”

New class issues

What also has become clear to her, in discussions after writing the book, is that AI can spur a new kind of class issue. That the world might be divided between those who are able to use the technology for their own benefit and those who aren’t.

“Someone said that AI will not take the journalists’ jobs. But journalists who know how to work with AI will take the jobs from the journalists who don’t.”

Inga got into the science world as a physicist. She wanted to understand the universe. Then, when she took her bachelor’s at NTNU, she noticed there was a field of study on artificial intelligence, and curiosity led her that way.

“My driving force is to find out what is possible. The main reason that I’m still in this field is that I see the consequences, and they are extremely complex.”

Even though she thinks about this complexity day and night, she also finds time to use that curiosity and energy on other things – mainly outdoor activities. Her social media is filled with pictures of her mountain biking, climbing and hiking. And those things are important.

“No matter what happens with technology and politics, there is one important thing that we can’t forget: to have a nice life. Human happiness must be our common goal – if not, nothing else matters. That’s very important to me to remember, every day.”

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Ann Axelsson

Senior Product Manager, Strategic Communication, Schibsted

Years in Schibsted: 25

My favourite song the last decade: Paper Doll – John Mayer

AI for good or for bad?

AI for good or for bad?

How will AI impact our lives and society? Joacim Lund compares it to the breakthrough that came with the internet – and sees many similarities. AI will solve many problems in our daily lives. We just need to make sure it doesn’t create new ones.

By Joacim Lund

AI for good or for bad?

How will AI impact our lives and society? Joacim Lund compares it to the breakthrough that came with the internet – and sees many similarities. AI will solve many problems in our daily lives. We just need to make sure it doesn’t create new ones.

By Joacim Lund

Artificial intelligence is a flop. Ok, not really. But we are talking about it the wrong way.

In Norway, an opinion piece from 1996 pops up on a regular basis. The headline of the newspaper clipping is crystal clear: The Internet is a flop.

Every time it appears, people have a good laugh. But the person who wrote it (incidentally, a reader I keep getting meaningful emails from) wasn’t irrational in his argument. He believed that people who work on computers will get more than enough of it during office hours (this definitely applies to some of us), that humans are social beings and, moreover, that it would not be profitable for business to offer their services online.

“When we rent our videos, we will visit the rental store and make our selection in visual surroundings,” he opined.

27 years later, much of the debate around artificial intelligence is not entirely dissimilar. People are either for or against artificial intelligence. They think it’s either good or bad. They think it will eradicate us or not. They want to stop it or let it be.

As new technologies arrive – the sceptics speak up. New habits sometimes take time to accept.

As new technologies arrive – the sceptics speak up. New habits sometimes take time to accept.

At the same time, AI developers from around the globe are creating autonomous weapons, racist algorithms and extreme surveillance systems that challenge human rights. Other AI developers are creating systems that revolutionise medical research, streamline the public sector, or help keep the temperature of the planet below boiling point. And everything in between.

The possibilities seem to be endless. So, shouldn’t we rather be talking about how AI can be used responsibly?

It’s changed everything

Today, everyone knows that the internet was not a flop. The authorities communicate with us using the internet. Ukraine and Russia are bombing each other using it. The propaganda war is almost exclusively waged online.

But perhaps even more importantly: the internet solves problems and has made life easier for most people. I charge my car online, pay bills and rent my videos (but sometimes I do long to go back to discussing movies with the movie nerd who worked on Bislet Video instead of getting flimsy recommendations by an algorithm).

I listen to my music online, remotely activate the heaters at the cabin, where I can also stream my news broadcasts. People find life partners online and discover like-minded people who also get excited by photography, old Italian scooters, 16th-century clocks, or Talk Talk bootlegs. We have access to everything, everywhere, all the time.

That’s why everyone laughs at the “flop” prediction. He was absolutely certain and he was wrong. But that’s easy to see in hindsight. And it’s hard to predict.

In 1996, people were concerned about Charles and Diana’s divorce and Bill Clinton’s re-election. Who could have imagined that Diana would die in a car accident in Paris a year later? Or that two years later, Bill Clinton would be explaining why his sperm was on a dress?

Or that the internet was going to change everything?

Tomorrow is only a day away

I have no idea how artificial intelligence will have impacted society, people and the lives we all live in 2050. But I see several similarities between the internet in 1996 and artificial intelligence today:

Artificial intelligence solves problems and will make life easier for most people. Artificial intelligence is changing assumptions.

Also for people who don’t have good intentions.

“Whoever takes the lead in this field takes the lead of the world,” Putin said during a live address to 16,000 schools at the start of the school year in the fall of 2017. By “this field” he meant artificial intelligence. Xi Jinping had recently launched an ambitious plan to make China a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

It almost makes you want to just ban the whole thing. Impose international sanctions and throw the baby out with the bathwater. The problem is that artificial intelligence opens up so many positive possibilities as well.

Things like evaluating X-rays, AI can solve much faster and better than humans.

Things like evaluating X-rays, AI can solve much faster and better than humans.

The toe is broken

I was once playing with my son. I chased him around the apartment, arms straight ahead, like a zombie. As I made my way around the kitchen table, my little toe hooked onto a chair leg. There was no doubt that the toe was broken. It pointed straight out to the side. Still, I spent most of the day in the emergency room.

The reason for this was a bottleneck in the system.

When people come in with minor fractures or just a suspicion that they’ve broken something, for that matter, an X-ray is taken. A doctor (the bottleneck) must study each individual image to see if there is a fracture or not. If there is no fracture, the doctor sends the patient home. If there is a fracture, the patient is placed somewhere on a priority list.

However, minor fractures are not life-threatening. If there is a lot to do in the emergency room, the X-rays will be given low priority until there is more time to look at them. When the doctor finally has time, he or she will study the picture and determine that there is no fracture – in about 70% of cases. The patient, who by then may have waited seven hours, is then told to go home, take two ibuprofen and three glasses of red wine (which my dentist once recommended), and turn on Netflix.

It’s things like this that artificial intelligence can solve much faster and better. And it’s already doing it, actually.

Level up

The other day I was visiting a hospital in Bærum, just outside Oslo. An enthusiastic, young, bearded radiologist pointed to an X-ray image on a screen in front of us. The picture showed a foot, and it looked quite similar to the picture taken once upon a time of my foot (except that the little toe didn’t point straight out to the side).

But one thing was different. The image had been assessed by an artificial intelligence.

Above the ankle bone, a yellow square had been drawn, lined with the text “FRACT.” That means there’s a fracture there. The software goes through all the X-rays as they come in. Seven out of ten patients are told immediately that they can go home. The rest automatically end up in a priority queue.

Doctors do not have to spend valuable time finding out that everything is okay, and patients do not have to wait. This is an extreme efficiency improvement in a health service that will experience greater and greater strain in the decades to come.

Should this have been banned? Some think so.

Sense and sensibility

A few months earlier, two Norwegian politicians warned that artificial intelligence leads to everything from polarisation to eating disorders, and perhaps even the extinction of humanity. The government should immediately “impose a public sector moratorium on adopting new commercial tools based on artificial intelligence,” they argued.

This is an absurd approach to artificial intelligence. The pressure on the healthcare system only increases as people age. To have any hope of maintaining good health services for the population, we must make use of the tools at our disposal. The AI tool at Bærum Hospital happens to be delivered already fully trained from abroad. All patient data is deleted, so as to avoid all privacy issues. Of course, there shouldn’t be a ban on such things. But the two politicians still had a good point:

“The development of AI has for a long time taken place without adequate regulation from the authorities.”

Now it’s happening

There has been a Wild West approach from the tech companies. Naturally. Development is rapid, and work on laws and regulations is slow. But the EU has been working diligently on the issue.

The EU’s first draft regulation of artificial intelligence, the so-called AI Act, was presented two years ago. It is likely to be formally approved within 2023. The EU is adopting a risk-based approach. For services that pose a low risk, it’s full speed ahead. Unacceptable risk means it’s prohibited. And for everything else in between, there are two more levels: acceptable risk and high risk.

The purpose of the AI Act is to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are safe and respect fundamental rights and values. This means, for example, that facial recognition in public spaces is banned. It’s not allowed to single out citizens for the authorities to keep an eye on in case they do something illegal. Stuff like that.

AI should be open and honest, not closed and manipulative. The resistance the AI Act has faced from tech companies suggests that regulation is needed. For example, Sam Altman, the man behind OpenAI and ChatGPT, has threatened to pull out of Europe if the regulations become too extensive.

Perhaps now it’s time to revisit the crystal ball.

A willingness to solve problems

In September 2023, Norway’s Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, held a press conference where he proudly announced that his government would allocate one billion Norwegian kroner to artificial intelligence research, to be used over the course of five years. On the same day, the government leaked that it would spend five billion on a new tunnel to shave a few minutes off the drive between two villages in the mountains of western Norway somewhere. But OK, a billion is money too.

A large and important part of the research will focus on how artificial intelligence can be used for innovation in industry and in the public sector. Like in hospitals, when people come in with sore fingers and toes. Or in building applications, so people don’t have to wait several months for the overworked caseworker to get far enough down the pile. Or to provide public services with a faster, larger and better basis for decision-making. Or to improve data security, in fact, and not worsen it.

And in so many other ways that I can’t possibly imagine.

That’s what politics is all about. To follow social developments and govern society in a way that makes it as good as possible for as many people as possible. Norway is just an obvious example because that’s where I live. The same goes for every other country and continent, and globally, for that matter.

As in other areas of society, international resolutions and treaties and sanctions must be adopted to ensure that artificial intelligence is used in a way that solves humanity’s problems, rather than create new ones.

That work is underway.

OK, here’s what the crystal ball says

If I’m going to allow myself to try to look 27 years into the future, to 2050, I’d guess that people are more concerned about themselves and their nearest and dearest, and not so much about what people were thinking back in 2023. But those who bother to read old newspapers might chuckle a bit at the banal discussions we had about artificial intelligence ’way back when.’ And the fact that many were either for or against. Maybe it’ll be the demand for a ban and the call to halt development that everyone will laugh at (try asking Putin to stop the development of artificial intelligence, by the way).

I’m guessing that my future grandchildren will experience an education system much more attuned to each student’s learning disabilities, learning styles and skills. That their health will be taken care of much better than by the GP they see every two years. That potential health problems will be discovered before they become major and serious. I’m guessing the car will be a safer driver than the human. That public transport will be much better adapted to people’s needs. That precise weather forecasts will control the heating in houses. That everyone will be better protected from abnormal activity, whether it’s in their bank accounts or in their apartments. Maybe I won’t have to think about shopping for food or cleaning the house anymore.

I’m guessing it will seem strange that society spent so much time and resources on having people perform repetitive and simple tasks. And that major and important decisions were made on a razor-thin knowledge base.

I am absolutely certain that artificial intelligence will be subject to international regulations. And that artificial intelligence will lead to global, regional, local and personal changes that are difficult to imagine today.

Because by then humanity will know better.

If, of course, it still exists.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Joacim Lund

Technology commentator, Aftenposten

Years in Schibsted: 18

My favourite song the last decade: Bråtebrann – Kverletak

On speaking terms with machines

On speaking terms with machines

We have interacted with our computers in mostly the same way for almost 60 years. But now we’re entering the age of conversational interfaces. Schibsted’s Futures Lab has experimented to understand more of their capabilities and constraints. The experience was surreal.

By Christopher Pearsell-Ross

On speaking terms with machines

We have interacted with our computers in mostly the same way for almost 60 years. But now we’re entering the age of conversational interfaces. Schibsted’s Futures Lab has experimented to understand more of their capabilities and constraints. The experience was surreal.

By Christopher Pearsell-Ross

With the invention of the mouse in the 1960s, command-line interfaces gave way to a visual paradigm defined by graphical user interfaces (GUIs). Icons, menus and windows made computing more accessible to more people, and more applicable to a broader range of tasks.

In the mobile age, we have left our cursors behind in favour of the touchscreen. Now more than ever, we are reliant on visual metaphors to interact with our machines. We discover, create and explore our digital worlds with clicks and scrolls, taps and swipes, but this reliance on two-dimensional GUIs does not fully reflect our shared vision of how future technology should look.

These visions, exemplified by scenes in science fiction film and television, help define our shared expectations for what our technology should be capable of. In the future we are often shown, machines will speak and understand us. They will know us, anticipate our needs, and for better or worse, have the agency to act on our behalf. Large language models and tools like ChatGPT appear to be changing the paradigm again, bringing these sci-fi visions closer to reality.

Developed in 1964

These conversational interfaces are by no means new. Eliza, the first convincing chatbot, was developed at MIT in 1964 using simple pattern matching and rule-based responses. Siri was launched in 2011 as part of iOS using machine learning to recognise speech and to make sense of our intentions, letting many of us speak to our computers with our own voices for the first time.

But these interfaces have been limited to the responses and actions their programmers pre-defined. AI might have changed the input side of the equation, but these tools are still a lot closer to Eliza than we might care to admit. Advancements in AI technology over the last few years are radically altering this equation.

The introduction of generative AI, built on advanced neural networks called transformers, is reshaping the way our computers understand, process, and even create text. These AI models are what revolutionary new products like ChatGPT are built on, but they are also driving incredible improvements beyond text generation, including new capabilities in speech recognition, voice synthesis, sentiment analysis, image and video generation, and even the creation of 3D assets and animations.

In the year since ChatGPT was released, several key tech trends are shaping the future of conversational interfaces. Context windows are growing, essentially giving these tools longer memories and leading to more nuanced and relevant conversations. These tools are also getting connected to external data sources and digital services, enabling them to provide reliable and referenced answers, perform calculations and data analysis, and even take actions on behalf of the user. Lastly, as a recent release from ChatGPT shows, these tools are becoming multi-modal, meaning they are capable of processing not only text but also audio and images as both inputs and outputs, further expanding their versatility.

Until now, conversational interfaces have been limited to pre-defined responses and actions. AI is radically altering this equation.

Until now, conversational interfaces have been limited to pre-defined responses and actions. AI is radically altering this equation.

Aside from technology, social trends are also shaping this conversational paradigm. Firstly, populations in the developed world are ageing as birth rates decline, life expectancies increase and immigration and healthcare systems struggle to keep up. At the same time, feelings of loneliness and isolation are growing. In 2022, the number of single-person households in Sweden grew to over two million, and in 2023, the US Surgeon General warned of the public health effects of a growing epidemic of loneliness. Finally, in many parts of the world, education gaps are also growing. Inequities like racial, gender and economic disparities mean more people around the world are left out and left behind when it comes to the opportunities that education affords.

Taken together, we are seeing signs that point toward a future in which we increasingly rely on our technology for tasks and companionship that have traditionally been performed by people. There are opportunities and risks here. Conversational tools might enable new forms of healthcare and companionship services, give knowledge workers new superpowers or provide personalised tutors to children who need them. And they might also replace human connection, displace workers, or widen inequities.

Conversational user interfaces can bridge the best of what computers and humans have to offer.

While looking at hypothetical scenarios and possible outcomes is an important part of how we inform our strategy, our mission at Futures Lab doesn’t end there. To learn more about what we can and should do today, we need to get our hands dirty with practical experimentation.

Speculative prototyping is like a kind of time travel – it allows us to rehearse possible futures, and to experience what it might feel like to be there ourselves. In this case, we built a phone powered by ChatGPT to learn about how we might talk with AI-enabled devices in the future.

Inspired by science fiction examples like Samantha from the film “Her,” we set out to build an audio-only interface. Our goal was to explore the technical maturity, usability and applicability of CUIs in today’s landscape.

We scoured Finn.no for a suitable device to house our new tool and settled on a 1970s-era Ericofon 700. To provide a context for our experiment, we decided to explore workplace productivity and set out to design a weekly de-briefing tool to help us reflect on our work and keep our stakeholders updated.

We were able to use the original speaker but replaced the dialling mechanism and speaker with a Raspberry Pi minicomputer, new microphone and a proximity sensor so we could tell when the phone was lifted. Using OpenAI’s Whisper service for voice recognition, we sent a transcript of what users said to ChatGPT using a custom system prompt. This prompt helps GPT know how to respond, what role to play and which tone of voice to use. Finally, the system’s response is played back to the user using Google Cloud text-to-speech functionality.

The result was compelling and eerily similar to some examples from science fiction. While you still need to take turns speaking and listening, the conversation flows fairly naturally. Our AI agent can ask highly relevant follow-up questions, keep the conversation on-task and help users reflect on their work in new ways. Once the system determines it has enough information (usually after a few minutes of back-and-forth conversation) it writes a summary for the user, which it can either re-write or submit to a database at the user’s instruction. From there the summaries can be used in any number of ways, from providing a searchable archive of our progress to creating tailored newsletters and Slack updates.

The audio-only experience allows us to assess what actually speaking with our machines in open-ended, flowing conversations might be like, without relying on the graphical and visual indicators we normally use.

Using these new interfaces has been as informative as it has been surreal. The scenes from “Her” and “Star Trek” that we took as inspiration are very quickly becoming reality. Testing prototypes like this can help us understand the capabilities and limitations of the technology, how to design usable products, and where and when CUIs are an appropriate choice.

Impressed with the quality

The people who have tested our phone interface were impressed by the overall quality of the conversations and the relevance of the follow-up questions. Being able to go off-script and have an actual voice conversation with a computer has been revelatory, though not without its frustrations.

Audio-only experiences are clearly outliers, but prototyping in this extreme format and comparing the experience to conventional chatbots has highlighted some important usability considerations. The things we may take for granted when using well-designed GUIs – namely, seeing the system status, understandable actions with clear icons and buttons, and information hierarchies that prevent cognitive overload – become more complicated when we only have our ears to rely on.

When it comes to usability and user experience, user preferences are strongly divided between the audio and text-based interfaces. Some users felt the intimacy, distraction-free focus, and ability to speak plainly without pretension or self-editing created a novel experience, one in which they were prompted to reflect and share a sense of openness and safety. Other users expressed a strong preference for text-based communication. They cited the efficiency of typing, the ability to refer to questions and previous answers, having time to formulate and edit their responses, as well as the ability to read and paste in other materials as important factors for them.

An important consideration in both text and audio-based CUIs is expectation management. These tools have come a long way and are able to converse at such a high level that many users will expect them to have capabilities and understandings far beyond their current capabilities. We can blame this partly on the quality of synthesised voices available today – the more human the system sounds, the more human we expect it to behave.

ChatGPT and other conversational tools like it are already demonstrating two key superpowers. First, they are great conversationalists and interviewers – they are able to understand our meaning clearly, provide tailored answers, and ask highly relevant questions. They are also able to translate human language into data consumable by machines, and to take complex data and translate it back into comprehensible human language.

We see these tools being most useful in contexts in which both of these abilities can be leveraged. Obvious applications include games and interactive media, personalised content production in news media, customer service, sales and product discovery. They are already proving highly useful as task-specific assistants in programming, research and data analysis, and we expect them to be applied as pervasive personal assistants and tutors in the very near future. Less obvious, and perhaps more far-fetched and ethically challenging, applications include AI therapists, healthcare advisors and personal companions for the vulnerable.

Combination of superpowers

Conversational user interfaces can bridge the best of what computers and humans have to offer. They can leverage the high-speed data analysis and computational superpowers of computers while making sense of the messy, creative and intuitive understanding we have as humans. In the best-case scenario, this combination of superpowers will help make the world more accessible to people with visual and cognitive differences, help make education more accessible and tailored to individual needs, increase our productivity at work and free up more of our time for the things that truly matter. On the other hand, these tools also have significant potential to disrupt labour with new forms of automation and to create emotionally impactful, biased content that drives further social isolation, misinformation, and inequity. The reality is that both scenarios are likely to coexist.

This is a rapidly changing landscape and things we thought of as science fiction are already becoming reality. We can’t predict the future, but through foresight and experimentation, we can better prepare ourselves for the changes, challenges and opportunities that are coming. That’s the approach we try to take at Schibsted’s Futures Lab. We are seeing a new paradigm of interaction on the verge of being born. CUIs have incredible potential to empower people in their daily lives… if we can get it right.

This text was human-generated by the Futures Lab team. ChatGPT was used as a sparring partner and writing critic throughout the process. Special thanks to our summer intern Lucía Montesinos for driving much of this work.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Christopher Pearsell-Ross

UX designer, Schibsted Futures Lab

Years in Schibsted: 2.5