Making used book sales painless

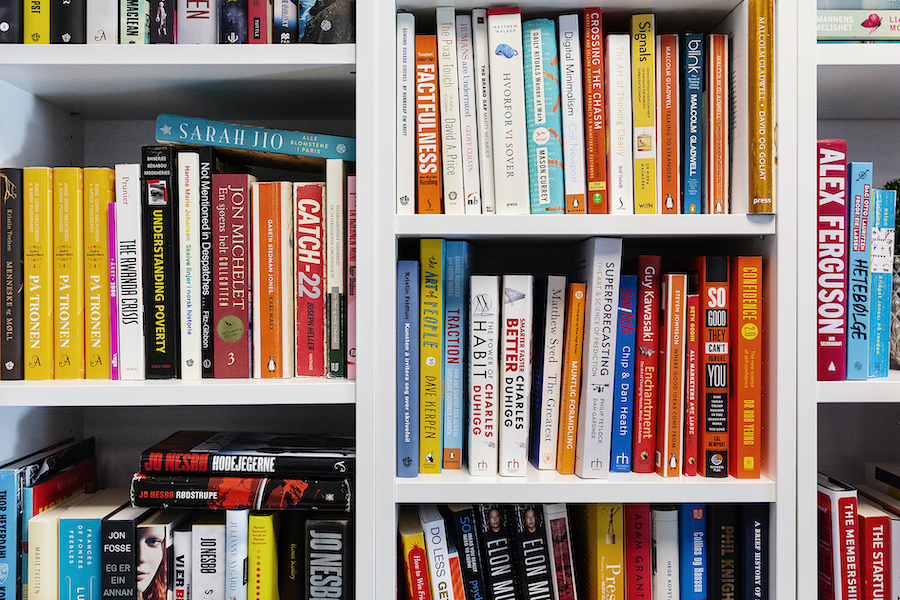

Lasse and Arne-Morten met in the armed forces, years before they started Bookis together.

Making used book sales painless

Bookis is a rare success story of literary entrepreneurship. In just a few years, the company’s online marketplace for used books has accumulated the widest selection of books in Norway, offering four times more Norwegian titles than its closest competitor.

With almost 300,000 users and more than a million titles, Bookis has established itself as an online treasure chest for book lovers in Norway and Sweden. On top of that, it has managed to shake up the old book publishing oligopoly. That doesn’t mean it’s achieved its goal, however – far from it.

But first, we need to go back to the beginning. Although the company wasn’t founded until 2017, we have to go all the way back to 2008 to find the true beginning of Bookis. More specifically, to the Norwegian Army Officer Candidate School in Indre Troms in northern Norway.

Because it was there, between the gun smoke and green army camouflage uniforms, that Lasse Brurok and Arne-Morten Willumsen first met.

A friendship that has lasted

“In the armed forces it doesn’t take long to get to know people on a deeper level. I think we both realised pretty quickly that this was a friendship that was going to last”, says Lasse.

The two young men served alongside each other for a couple of years before Arne-Morten packed his bags and moved to the United States to study finance. Lasse continued his career in the armed forces alongside working as a street artist. Even though they lived on different continents, their friendship remained strong.

When Arne-Morten returned to Norway a few years later, he got involved in a number of startups. In one of them he was responsible for the company accounts, and was tipped off about a book on Norwegian accounting rules. Because it was so expensive, he decided to find a used edition. That turned out to be more difficult than he expected.

“I came across sellers who never turned up at the agreed time, and there was no easy way to pay. It was shocking to see how difficult it was to buy a used book. In the States it was easy to buy used books via Amazon, but a similar service didn’t really exist in Norway.”

An idea began to form in Arne-Morten’s head. Recycling and the circular economy were more popular than ever before, and e-commerce in the Nordics was growing by as much as 20 percent annually. Could it really be that hard to set up a one-stop shop for used books?

“For people to even bother to sell a used book, the threshold has to be very low. No one is willing to spend a lot of time and energy on earning a hundred-krone note”, says Arne-Morten.

His idea gradually evolved, and in 2016 he shared it with Lasse over dinner. Before the evening was over, they had officially founded Bookis. Since that day they’ve never looked back.

In the beginning there was a lot of testing and failing. The first proper experiment involved turning a class of students at the BI Norwegian Business School into a concrete case. All the useful input they got from the students was used in the further development of Bookis.

“We used lean methodology and based our work on the build-measurelearn model. Through testing and failing, we gradually understood what worked and what didn’t”, says Lasse.

After a while they found themselves facing their biggest challenge so far: how would they get the books from the seller to the buyer?

Helthjem became a turning point

“The big turning point came when we called an acquaintance who’d recently got a job at Helthjem. They had just started to develop a new service called Me to You, that would make it super easy to send packages between private individuals. What an amazing stroke of luck!” says Arne-Morten.

Helthjem and Bookis developed their services in parallel, and launched them simultaneously just before Christmas in 2017. While everyone else slept during the dark winter nights, Helthjem’s couriers collected and delivered used books all over the country, from door to door.

“Getting the agreement in place with Helthjem was undoubtedly the most crucial factor to our later success. It’s like the stars were aligned”, says Lasse.

Since then, Bookis has worked continually on improving and simplifying its user experience. Integrating a function to enable customers to scan the barcode on the books they want to sell was a milestone. This allows Bookis to find all the information about the books and enter it into the system automatically.

To expand its selection, Bookis has also started selling new books at competitive prices. But it is still the used books that make up most of the inventory. The used books are also sold at a fixed price, which means that sellers don’t have to deal with hagglers.

It’s up to the buyer and seller to decide whether they want to meet in person or use Helthjem’s delivery service. If they choose Helthjem, the buyer pays the shipping charge.

“Sellers perceive us as a marketplace, while buyers perceive us as a regular online book store”, says Arne-Morten.

One thing that shocked Arne-Morten and Lasse when they entered the book industry was that Norwegian authors receive only 15 percent royalties on sales of their books while the publishers rake in the rest. On top of that, it is the publishers that own the copyrights. Arne-Morten and Lasse thought this was a really bad deal.

“We think the conditions for authors are bad enough to start with, and that they also deserve to earn money on the books that are sold on. So we developed a function for this. Buyers on Bookis can opt to add an amount of their choice as a royalty to the author when they buy a used book. So far we’ve collected more than NOK 700,000 for Norwegian authors”, says Lasse.

A good culture is most important

Product development and the business side are perhaps the two key aspects for many young entrepreneurs, but for Arne-Morten and Lasse, the top priority has been to build a good company culture. And they thank the armed forces for that. They describe the Norwegian Army Officer Candidate School as a kind of crash course in leadership.

“Our philosophy is simple: look after the staff and solve the task – in that order. Our goal has been to nurture a good work environment with a high level of psychological safety. Without a healthy and positive culture based on trust, we will never succeed”, says Lasse.

In a safe space, there’s nothing dangerous or frightening, and that includes talking about your own mistakes or showing your vulnerability.

“We often discuss our own mistakes and what we have learned from them”

“Lasse and I have always been good at challenging each other, even in front of colleagues. But it’s done out of love, and out of a shared desire to succeed. And we often discuss our own mistakes and what we have learned from them. More leaders should be better at showing that they’re just humans, too”, says Arne-Morten.

And no one in Bookis gets applause for working long hours.

“We want people to have a healthy life-work balance. We come and go at normal hours, and when we leave work, we turn of all the job-related notifications on our phones. There’s nothing cool about working yourself into the ground or sending e-mails to everyone at all hours”, says Lasse.

They’ve also introduced meeting-free Wednesdays and are happy if colleagues don’t reply to e-mails or messages on Slack during the workday. “That just

means that they’re focusing on their tasks and are not letting themselves be interrupted by all those time stealers”, says Lasse.

And it seems that both the business model and their leadership philosophy has worked; after only four years, the arrows are pointing upwards for Bookis. But where do they go from here?

“We’ll keep banging away, and we will definitely work closer with authors in the future. We’re not quite ready to reveal our specific plans just yet. The only thing I can say for sure is that it will be totally cool! And that Bookis will be a well-known name on a lot more people’s lips”, says Arne-Morten.

This is Bookis

Norwegian launch: December 2017.

Swedish launch: September 2020.

Number of users: 285,000 (70,000 in Sweden).

Number of employees: 26.

- Bookis offers a four times larger assortment of Norwegian titles than its competitors.

- Offers a mix of fiction and non-fiction titles.

- The first in the world to launch a royalty program for used books.

- Aims to expand into new markets.

- Has a revenue of over 50 million NOK in 2021.

- Schibsted made an initial investment in Bookis in 2019, and today owns 29.3 per cent of the company.

Linda Christine Strande

Communications Manager

Years in Schibsted: 3

With the power to save the climate

When eight of the world’s largest seafood companies got together they realised no one would benefit from polluted, depleted oceans – so they decided to change things. This is one of the stories told at the executive programme for CEOs.

With the power to save the climate

Greta Thunberg is not the only one listening to the science. CEOs of companies that generate almost half of Sweden’s GDP have returned to the classroom to learn about climate science and action. When deep insight about the climate crisis reaches this level of decision-making, real change can come about.

It’s thanks to Lisen Schultz that the Swedish CEOs decided to clear time in their busy schedules to take the course. In 2018, she transformed what began as an annual event into an executive programme for CEOs at the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University.

Standing alone on the stage under the strong lights, she felt the conviction grow. The worst thing had already happened to her, and so she had no fear left. Her husband, and father of her three children, had died in a bike accident in the mountains outside Nice, and now she stood there with all eyes on her. The room was filled with Sweden’s top business leaders, invited journalists and researchers, who had come to discuss sustainability and what could be done to speed up the transformation.

In memory of her husband, Lisen Schultz wanted to shape a business sector that respects the planetary boundaries and nurtures human potential. He had been editor-in-chief of a number of financial newspapers, and was passionate about issues like gender equality, diversity and sustainability in business. As a sustainability scientist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Lisen saw a path along which his work could be taken forward.

Looking for a stronger impact

Amidst all the chaos that ensued from the accident, she created the foundation that bears his name: the Pontus Schultz Foundation for more humane businesses. But as the climate crisis accelerated, Lisen wanted the foundation to have a stronger impact on action. And even though her grief had caused her to doubt, it all started there on a stage in the glare of a single spotlight.

No sooner said than done; one day in early autumn, the taxis rolled up and Swedish business leaders – major shareholders like Jacob Wallenberg, Tomas Billing, CEO of Nordstjernan, Henrik Henriksson, CEO of Scania and Axel Johnson’s Pia Anderberg – entered the researchers’ domain and took their seats. As a whole, the class generated a substantial share of Sweden’s GDP and accounted for CO2 emissions twice the size of Sweden’s. It was mind-boggling, but the power of science gave Lisen a new glimmer of hope.

“With lectures being given by world-leading researchers, the message would be clear and no one would shy away from ruffling a few feathers, I knew that. But I had no idea whether or not it would work.”

“The planet has financed our way of life. Now the invoices are arriving.”

Professor Johan Rockström took the classroom floor: “The planet has financed our way of life. Now the invoices are arriving.” He then proceeded to describe the anthropocene – the geological epoch in which humans shape the climate conditions – and the safe operating space for humanity.

“Four planetary boundaries have already been crossed, while others are dangerously close to their respective tipping points. The situation is dangerous but we can still change direction”, he explained. Members of the audience started shifting in their seats, and that was before Kate Raworth, economist and creator of Doughnut Economics, took the stage and insisted that economic theory had to be adapted to the planetary boundaries; a radical message that challenged the idea of infinite growth and maximum profit.

Not everyone agreed, and loud discussions ensued, but eventually the discussion shifted towards what could be done. Participants identified actions they could take in their companies, but also who else they could influence in order to achieve zero emissions, such as suppliers, employees, customers, competitors, investors and politicians. Companies can influence the world’s development, and the course participants realised they were not making the sustainability journey alone. The nightmare soon became a dream.

It needs to be In a company’s DNA

“You can’t base a transformation on a separate sustainability strategy. Clear goals are all well and good, but sustainability must be in a company’s DNA, corporate culture and governance. Changes will only last if they’re value-driven; only then will employees get onboard”, said Henrik Henriksson, CEO of Scania. The others nodded in agreement.

So far around 50 or so CEOs and owners – and even Crown Princess Victoria – have been trained by Lisen Schultz and her colleagues. But, once they’re armed with new knowledge about circularity, resilient systems and planetary boundaries, what can business leaders do? What obstacles can they overcome together? And what system of governance could accelerate this sustainable transformation?

According to Lisen Schultz, there’s a limit to how much a company can achieve single-handed to, say, reduce emissions or recycle resources. And the playing field is often tilted towards unsustainability, since many business activities don’t have to bear the costs they impose on society.

“This is where politics plays a big role at global, EU and national level; there’s no getting away from it. But companies of this size can influence politicians, especially if they join forces. That power grows strong during the course”, says Lisen.

The regulations are often decided by the politicians, and they can be about introducing bans, subsidies or taxes and duties aimed at steering the market away from whatever is fossil and resource-intensive and towards circularity and sustainability. EU’s emissions trading system and the carbon tax levied in Sweden and 26 other countries is one example. The fact that New York City pays landowners around the Hudson River to have their trees and wetlands clean the water that runs into the city taps is another one. In other words, governance systems can be large-scale and comprehensive, as in the case of the EU’s taxonomy regulation, which benefits sustainable businesses or, as in the case of New York City, can work on a smaller scale in a specific area.

In the near future the discussion will become even more forward-looking

Of course, not everyone is convinced, but in the near future the discussion will become even more forward-looking. What are the barriers to the sustainability transformation which owners and customers are slowly but surely demanding? What can promote and accelerate the green transformation, and what leads to reluctance, stagnation and “business as usual”?

“Harming the planet should be expensive, but it is not”, says Lisen Schultz.

“Having to make financial concessions often leads to relocations, but there are cases where actors actually succeed in changing the playing field simply by working together. This may sound rather banal, but bear in mind that ten companies control almost three quarters of the world’s oil reserves or that five companies account for 90 percent of global palm oil production. Our future lies in the hands of a few companies.”

She sees the situation as serious, but just as it’s possible to see which companies are actually creating pollution, it’s also possible that they can be part of the solution. Because if the five companies that own almost all of the world’s palm oil production were to decide not to sell palm oil from chopped-down rainforests, the whole playing field would change overnight. And while the world’s three biggest carbon emitters – China Coal, Saudi Aramco and Gazprom – are unlikely to adapt as long as they’re earning money with the current model, there are others who are taking a stand nonetheless. The Danish company Ørstedt previously supplied gas and oil but decided that offshore wind was the future for itself and for the planet, and reduced its emissions by 86 percent over ten years. And its profits remain high and are continuing to grow.

13 companies made an agreement

Carl Folke, professor and founder of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, gives lectures in the course and has, among many other things, led a ground-breaking study on the global seafood industry. Most of this team know that a growing global population and a changed climate make onshore crops even more unpredictable. But most people don’t realise that the world’s oceans feed three billion people. Unfortunately, this food source is also threatened by overfishing, acidification, pollution and algae blooms, leaving the fishing industry under threat on multiples fronts.

Carl Folke and his fellow researchers have shown that 13 companies dominate the global seafood industry, yet they all rely on the same resource, so if they could sit down and talk to each other, would they manage to reach agreement on a form of exploitation that would benefit everyone while still being more or less beneficial to the oceans? No sooner said than done; the researchers succeeded in gathering eight of the biggest seafood companies in a neutral place where they could discuss the situation together. It suddenly became clear to everyone sitting around the table – who came from different countries and cultures – that there was only one way forward and that they all faced the same threats of pollution, acidification, antibiotic resistance and overfishing. But the biggest insight was that, together, they could make a difference without removing the competition between them. They could quite simply agree to, for example, improve working conditions, exert influence on laws and regulations, and make it easier for consumers and authorities to track fish from vessel to table and how they are caught, which would reduce the risk of poaching. From that point on, it was a short step to setting sustainability goals, taking responsibility for supply chains and avoiding highly vulnerable areas. Because no one benefits from polluted, depleted oceans.

Despite all her knowledge about the global situation, Lisen Schultz remains an incurable optimist, and she believes that climate communication represents an untapped resource.

“Martin Luther King didn’t say ‘I have a nightmare’; instead, he painted a vision of the future where black and white people lived as equals. The same logic can be applied to climate communication. Most of us want the best for the planet, for their own sake and for that of their children, but we need help to achieve that.”

It’s about setting scientifically informed goals, taking control of our climate footprint and working locally. It’s not about adopting an anorexic lifestyle; it’s about doing whatever we can at every opportunity and cooperating on reaching our goals within the planetary boundaries.

“It is in business and industry that those heroes are found”

The business leaders in the classroom in Stockholm also got a strong message from Nigel Topping, appointed by the British government as High-level Climate Action Champion, tasked with raising industrial climate ambitions in the preparations for COP26:

“Every disaster film has heroes who refuse to give up and who find a way forward. When it comes to the climate, I’m fully convinced that it is in business and industry that those heroes are found”. According to Topping, the Paris Agreement came about partly through the united voice from hundreds of leading companies who supported an international climate agreement.

Most business leaders agree that goals need to be realistic and time-bound. But at the same time, ambitious goals are pushing the boundary of possibilities, in the same way John F Kennedy did, when he decided that a moon landing should happen. This clear goal and a solid pot of money released creativity and mobilised initiative; the impossible became possible.

Lisen now sees parallels between her own story and personal loss, and how all of us now need to adapt to a new reality, however painful that may be. But to be able to do it, we must have a vision, a goal and a plan that is sustainable, one that enables us to take a first step on the journey, together. Because that’s how we humans work. Life always finds a way.

Erica Treijs

Reporter, SvD

Years in Schibsted: 20

Protocols, tigers and unicorns

Protocols, tigers and unicorns

2021 is a time of change for entrepreneurs raising venture capital, and for the firms providing it. For founders, there has never been a better moment to start a company and seek funding. Dan Ouchterlony, EVP Financial Services and Ventures, looks into an exciting future.

Venture capital is booming. In the third quarter of 2021, a whopping 158.2 billion USD was invested into start-ups at various stages, according to CB Insights. This is more than double the investment compared to the third quarter 2020 (which itself was a strong quarter!) and the highest number on record for a single quarter.

The driver was the volume of large rounds, totalling 409 investments of more than 100 million USD, up from 173 in Q3 2020. However, at the end of the funnel, exits have only increased 13 percent in 2021, as compared to 2020. Thus, an increasing amount of wealth is tied up in start-ups.

This prompts many questions. What are the driving trends in the industry, and why is interest booming? Who are the movers and shakers? And what is happening on the fringes? Is the rising tide lifting all boats, or are some players at risk of losing out?

Masayoshi Yasumoto was bullied as a child. Despite being third generation Japanese, he was considered ethnically different. In his adolescence he agonised over his identity to the extent that he seriously contemplated taking his own life. Today he claims, somewhat credibly, that he is the Rothschild of the Internet era. But you know him as Masa-san – the CEO of Softbank and chairman of The Vision Fund, the world’s largest venture capital fund.

Masa and The Vision Fund came blazing on the venture capital scene on 20 May 2017, with the announcement that they had closed 93 billion USD of commitments to the fund. Compared to the 153 billion USD of venture capital invested in 2016, this was a staggering number by all accounts. By September 2019, all the funds were deployed, except a small reserve, and venture capital was changed at its core.

The Vision Fund changed the game by being more aggressive than other venture capital firms, both in terms of how much capital they deployed into their investments and by threatening to fund rivals. Established venture capital funds lost out on deals, as Masa-san was willing to raise valuations, and effectively bought his way into deals using both carrot and whip. Seen as a king maker in the segments they entered,founders and CEOs jostled to stay behind, rather than in front of, what Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s CEO, famously called “the capital cannon”. What happens if Softbank funds my rival, wasn’t a rhetorical question.

The canon has not reloaded

Softbank and The Vision Fund also played a different game in the public arena. Whereas many established venture capital players relied on building relations, understated communication, and thought leadership in their industries, Masa-san went on stage with slogans like “happiness for everyone” and slides with pastel-coloured unicorns and golden geese.

The Vision Fund’s capital cannon has not been able to reload, however. And due to the poor financial results (so far) of Vision Fund 1, Vision Fund 2 has shrunk dramatically in comparison. With the aim to raise 108 billion USD, the fund has only raised 30 billion USD to date, all of which is committed from its owners at Softbank.

Was it then a historical blip on the radar? Some of what happened might be told as a cautionary tale for the next generation of venture capitalists during fireside chats. But one thing is for certain. Masa-san is not finished. He is not a stranger to failure after losing some 70 billion USD of personal wealth in the dotcom crash, and rising taller from adversity, as exemplified by changing his family name from their Japanese-assumed name of Yasumoto back to his family’s original Korean name Masa Son.

One thing that seems to have permanently changed in the wake of The Vision Fund is the speed of execution in large deals. But today, the velocity of deal making is no longer the hallmark of the “Unicorn Hunter”, but that of the “Tiger”.

But today, the velocity of deal making is no longer the hallmark of the “Unicorn Hunter”, but that of the “Tiger”.

Tiger Management was one of the largest hedge funds of the 1990s. After a bout of poor performance, it closed in 2000. Out of the ashes of the fallen fund, some 30 young managers in the team were staked to start their own hedge funds. One of them was Tiger Global Management – the Tiger that we know and talk about in the venture capital business today.

Tiger is, so far during 2021, closing about 1.2 deals per business day. This speed is unusual even for the predator: according to Crunchbase, 240 investments have been made as of 11 October 2021, up from 80 deals during the whole of 2020, and 86 deals in 2019, during the same period. In other words, Tiger is running three times their already high speed.

Pundits are commenting that Tiger is “indexing” the venture capital market, in a move characteristic of a hedge fund. Not a cannon perhaps, but a machine gun. The theory goes that if they spread their bets widely enough, they will hit enough success cases to generate returns.

What does this mean? First, let’s look back. The venture capital business is traditionally based on long-term relationships, which in and of itself means investing a lot of time per deal and trying to add value after the deal is done. It’s a model taken “to the next level” by Andreesseen Horowitz, who famously built the largest support staff in the business and financed it by forfeiting their own management fee. Despite Tiger’s extremely big staff, doing and supporting 240 deals in three quarters is just not sustainable on this conventional model. So how does Tiger do it?

Tiger does not build relationships

They do it by effectively employing the opposite of the conventional wisdom. Tiger does not build relationships in advance of sending term sheets. Tiger does not want a seat on the board. Tiger does not want to do heavy due diligence. And Tiger does not try to support you operationally after the deal. This indexing of bets has already happened to some extent in the earlier stages, where organisations such as Ycombinator and 500 Start-ups have tried to spread their bets very widely by speeding up investing. But with the sheer amount of early-stage rounds happening, the index will never be even close to complete. Tiger, on the other hand, has a real shot in the later stages.

The result of Tiger’s approach for founders is better, faster and cheaper capital, according to Everett Randle of Founders Fund. Start-up founders can spend less time raising funds and can for good and for bad, take capital without giving up control. This is attractive for many, and only the biggest, most successful venture brands will survive long-term with the established relationship model, according to Everett. The mid-sized firms will be squeezed by Tigers and the like, who are forging ahead with extreme conviction.

For venture capital this means many more people want to get involved

Another phenomenon on the rise, both in general and especially among the young, is decentralised finance. Technical terms such as blockchains, crypto currency and non-fungible tokens (NFT) are becoming mainstream. There are two things going on at the same time: First, access to and interest in capital markets are on the rise generally, boosted by players such as Robinhood and the get-rich-quick FOMO in the longest of bull markets. Second, entirely new technologies that decentralise and democratise finance – defi in short – are on the rise. One example is investor-entrepreneur from generation Z, Jacob Clearhout, left his firm to “do a start-up” at the intersection of VC and defi. In a fantasy football game for start-up shares called Visionrare, fake shares are minted as NFTs, sold for five USD each, and then made investable in a game of I-told-you-so.

For venture capital this means many more people want to get involved, both as venture investors, builders, speculators and commentators. One particularly interesting topic is the attack on the existing power structures in venture capital. As an industry that typically builds on apprenticeship, personal networks and significant personal wealth, it is somewhat uncomfortable to have young talent discuss tips for “breaking into VC”, “discrimination of non-white founders”, and why it is time to “ban the warm introduction”. According to Del Johnson, who launched the proposed embargo, the network-based approach of personal introductions is not only anti-founder and discriminatory, but even worse, it leads to subpar performance. Why? Because you miss the opportunities outside your network.

What is even more uncomfortable for many are defi structures that emulate and disrupt the venture capital firm itself. On the bleeding edge of development there are venture capital initiatives on the blockchain, structured as decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). Either these new structures appear for a special purpose, such as when the digital artist Pplpleasr auctioned off one of his works. And the winning bid was placed by some 30 individuals who organised on social media, gathered the funds, and formed a joint investment DAO in the matter of days. Incorporating an investment firm is a much slower process.

Votings are held in public

Pleasr-DAO has since invested in art by Snowden and Wu-Tang Clan’s album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, which they bought from the US Department of Justice, who in turn seized it from original buyer, pharma profiteer Martin Shkreli.

Another type of DAO can be a more general “VC on the blockchain” structure, such as when Singaporian cryptoexchange Bybit launched the 540 million USD investment vehicle Bit-DAO in September 2021, with external funding from Peter Thiel and Founders Fund among others. To be clear, this is a half billion-dollar VC firm in a protocol where partnership meetings (voting) are held in public, investment proposals are openly scrutinised (in a forum) and the governance model itself is defined by code.

The idea is not new. In April 2016, the first DAO named “The DAO” was launched, raising about 150 million USD worth of crypto currency from more than 11,000 investors through crowdfunding. At the time around 14 percent of all Ether in issue was owned by The DAO, with plans to become a fully decentralised venture fund. However, the code running this particular firm was flawed, and after losing a third of the capital to a hack, The DAO was delisted, and the project was disbanded. To recoup the losses, the actual blockchain underpinning The DAO was split in two, and the transactions were annulled. If not for the false start, many believe DAOs would have had a much more prominent role today.

As if this wasn’t enough, traditional venture capitalists also face a new generation of investors who are starting out their careers with a new focus and modus operandi, which just might be the future.

Meagan Loyst, investor at Lerer Hippeau is the founder of Gen Z VCs, a network of more than 10,000 who identify with the community of investors and entrepreneurs born after 1995. On her Medium page she published that the number one trend this group is interested in is the creator economy (Roblox, TikTok, UGC, etc.).

Their takeaway is that people see the path to becoming a creator as more institutionalised, and from a young age. Is the same happening to VC in general? The lines between entrepreneurship, investing and creating are certainly blurring. Many entrepreneurs are also angel investors and vice versa. Young VCs are obviously not afraid to network, entirely on the outside of the traditional pipelines of the firms; they are not afraid to make their voices heard; and topics of sustainability, inclusion and equal opportunity are on the rise.

If you are a venture capital firm today, your cosy corner of the market is under attack from many sides: Hedge funds trying to index your asset class “from above”, angels and young VCs banding together online, and blockchain tinkerers trying to democratise your privileged access “from below”. And there you are stuck in the middle. What will you do?

You could adapt and beat Tiger at their own game, like Sequoia China seems to have done. While Tiger takes the media headlines, the semi-independent Chinese arm of industry titan Sequoia made ten more deals in Q3 2021 than Tiger did, according to CB Insights. Does this mean entrepreneurs who take Sequoia China on board as investors will not get the gold standard support of Sequoia?

Only time will tell. In late October 2021 Sequoia announced they will go even more in Tiger’s direction by dropping the traditional a 10-year fund-circle, staying post IPO in the most promising companies. In practice they are becoming a hedge fund.

You could also double down on the current strategy, like it seems Andreesseen Horowitz has done in the crypto arena, by building out its investment and

support teams with roles such as crypto counsel, protocol specialist and crypto network operations. At one point, A16Z Crypto recruited so fast, it became a Twitter meme. According to the Information staff has almost tripled in four years.

Who will succeed? Will Tiger be able to show good returns on their massive bet and reload their capital machine gun? Can the established firms catch up? Or will doubling down on the proven approach work best? Over time, might the coming generation build new kinds of protocols and networks, making the firm itself obsolete?

2021 is a time of change for venture capital, and for founders there has never been a better time to start a company and raise capital.

Schibsted Ventures

- Schibsted Ventures represents corporate venture capital (CVC), a segment of venture investing that has been stable at 16–17 percent of the market, both during the more stable period in 2018–2020 and the explosive growth of 2021. We compete for the best investments using venture capital plus the potential benefits of the corporation’s assets, resources and insights.

- Our objective is to generate returns, but equally important is to speed up execution on our vision by supporting entrepreneurs who share our view of the future. This is a version of A16Z’s hands-on strategy if you will, but in another setting.

- Top CVC investors in Q3 2021 were Coinbase Ventures, Salesforce Ventures and Google Ventures according to CB Insights.

- Are you an entrepreneur in the Nordics, passionate about themes such as transparency, sustainability and empowering people in general? Reach out!

Dan Ouchterlony

EVP Financial Services & Ventures

Years in Schibsted: 16

Stuck in the world of big tech

Stuck in the world of big tech

It’s been a rough few years for a handful of US tech companies, due to a seemingly endless stream of scandals and harsh criticism from politicians on both sides of the Atlantic. The result? “Big Tech” is bigger than ever. But what if they have only started to flex their muscles?

Several executives reacted with shock, according to the people in the room. The proposal meant crossing a line, unleashing a hitherto unused weapon. The code name was “Project Amplify”, and it was a new strategy that social media behemoth Facebook hatched in a meeting in early 2021, as reported by the New York Times. The mission: to improve Facebook’s image by using the site’s News Feed-function to promote stories that put the company in a positive light.

The potential impact is enormous. News Feed is Facebook’s most valuable asset. It’s the algorithm that decides what is shown to users when they log in to the site. In essence, it is the “window to the world” for their users, who, totalling nearly three billion, constitute more than a third of all humans on planet Earth.

“Truth” is now the same as “what makes Facebook look good”

For many years Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg defended the company’s policy on free speech with the mantra that the social network should not be the “arbiter of truth” online, i.e., they would not censor content that people posted. Critics would say that Facebook has been doing this all along, letting its algorithms prioritise what is presented to users. What shows up in the News Feed is what people perceive as important, a form of personal truth for every individual. “Project Amplify” would mean something entirely new. By actively promoting positive news stories about the company, “truth” is now the same as “what makes Facebook look good”.

Silicon Valley veteran and social media-critic Jaron Lanier referred to the major social media networks as “gigantic manipulation machines”, possessing the power to alter emotions and political views among billions of people by pulling digital levers. Now Facebook has decided to use its machine for its own purpose.

We will return to the implications of this, but first, it is important to understand why Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg would want to do this. It is no bold assertion to say that Facebook’s public image is in acute need of a facelift. The company has been plagued by scandals for years. In 2018, it was revealed that the company Cambridge Analytica had harvested data from 87 million Facebook users, data that had been used in Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. The revelation not only tarnished Facebook’s reputation, but it also had real financial consequences. When the story broke in March 2018, Facebook’s stock tanked. In July the same year, Facebook announced that growth had slowed down due to the scandal. The stock fell 20 percent in one day. In a few months, 200 billion USD of the company’s market capitalisation was wiped out.

Facebook’s reaction can be summarised as follows: we are sorry and promise to do better. This has been repeated every time new, negative stories about the company emerge, such as the spread of disinformation, the negative impact Facebook’s product has on the mental health of young people, and how the network was used to instigate genocide in Myanmar, among other things.

If the stock market is a reliable gauge of the future, and it often is, the conclusion is clear: these companies are untouchable

But behind the many apologies it seems Facebook has continued with business as usual. In September 2021, the Wall Street Journal published “The Facebook Files”, a damning investigation showing that the company, including Mark Zuckerberg, was very aware of the harm the platform was causing. The company’s own researchers identified problems in report after report, but the company chose not to fix them, despite public vows to do so.

From the company’s perspective, its strategy has been a success. Advertising revenues have continued to rise and in autumn 2021, Facebook’s stock market value broke one trillion USD, double of what it was before Cambridge Analytica.

The same can be said of the other tech giants. Companies including Google, Amazon and Apple have been at the crosshairs of public debate for years, both for alleged abuse of their dominant market positions and for the negative effect their products and business models can have on people and society.

But if the stock market is a reliable gauge of the future, and it often is, the conclusion is clear: these companies are untouchable. Despite a storm of criticism, court cases and billion-dollar fines, stocks have continued to propel ever upwards. How is this possible? Let’s start with breaking down the different ways Big Tech dominates the world today.

When discussing this topic, parallels are often drawn to the influential corporations of the late 1800s and early 1900s, Standard Oil for example. These comparisons are misleading. Standard Oil and its owner John D. Rockefeller could never dream of the amount of power that rests in the hands of the Silicon Valley-titans of the 2020s.

The new economic superpower

In 2010, the total market cap of Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon was more than 700 billion USD. That was equivalent to the GDP of the Netherlands. The ascent had been amazingly fast; at this point Amazon was 16 years old, Google twelve and Facebook only six. In autumn 2021, their combined value had reached 9,500 billion USD, more than the GDP for Japan and Germany combined. The total annual revenue for these five corporations is north of one trillion dollars, more than the defence budgets of USA, China, and Russia combined.

The market superpowers

Facebook owns four of the five largest social media networks in the world. Google, owner of the second largest (Youtube), has a 92 percent market share on search. Apple’s and Google’s operating systems, IOS and Android, control 99 percent of the global smart phone market outside of China. Apple takes in 65 percent of the global revenue on mobile apps, and Amazon has 50 percent of the e-commerce market in the US, as well as 32 percent of the global market for cloud services, followed by Microsoft. The list goes on. This not only creates huge profits but also creates an enormous asset in form of the 21st century’s most valuable commodity: data.

The innovation superpowers

Up to 50 percent of the venture capital raised by start-ups circles back to Google and Facebook in the form of advertising, almost as a “tax on innovation”. If new, competing services emerge, Big Tech can either try to buy them or launch competing products. Their headway in terms of resources and user base makes it extremely difficult – if not impossible – to pose a real threat.

The perception superpowers

Twenty years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, one in 16 Americans believe the US government knew about the attacks and let them happen. Conspiracy theories and disinformation have become the new normal, and research has shown social media plays an important role. What Google and Facebook choose to allow, or not allow, on their platforms shapes our view of the world. In 2012, Facebook conducted an experiment among 700,000 users to see if their states of mind could be altered by changes in News Feed. The answer was yes.

The infrastructure superpowers

In December 2020, Google went down, meaning users could not access Gmail, Google Docs or Youtube. Although the outage only lasted 45 minutes, it made headlines all over the globe. The same thing happened to Facebook in October 2021. As an expert said to CNN: “For many people Facebook is the same as internet”. After the 2008 financial crisis it was clear that a small number of banks were “systemically important”. This is now very true for Big Tech. Serious disruptions in their services would quickly have severe and costly consequences.

The political superpowers

Big Tech has surpassed Big Oil as the biggest spenders on lobbying in Washington D.C., with an increase in spending from 20 to 124 million USD between 2010 and 2020. In the election cycle of 2020, a total of 2.1 billion USD was spent on political ads on Facebook and Google. In a manifest published in 2017, Mark Zuckerberg noted that in elections across the world “the candidate with the largest and most engaged following on Facebook usually wins”. In other words: use us or you lose.

The capital markets superpowers

It could be argued that the stock market has become the most important gauge for global decision-makers. It takes decades to make them do anything to combat climate change, but if stocks drop dramatically, decisive action from politicians and central banks are delivered within days or even hours. This was last seen in early 2020, when fears of the economic impact of the pandemic brought the Dow Jones down by 13 percent in one day. The direction of the stock market is, in turn, more and more intertwined with that of Big Tech. Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft constitute a quarter of the S&P 500 index.

The AI superpowers

“Dark patterns”. That is what scientists call the tricks that digital companies deploy to manipulate users. Sometimes the purpose can be quite trivial, like making people sign up for a newsletter or share their email. The point is that you as a user do something that you didn’t intend to do. With artificial intelligence these tools become more and more powerful and potentially deceptive. The more data an AI-algorithm can use to train on, the more effective it becomes. This places Big Tech in a unique position to use these techniques. The problem with this is best summed up by Meredith Whittaker, a former Google engineer and now head of the AI Now Institute at New York University: “You never see these companies picking ethics over revenue.”

In all the ways mentioned above, the power of Big Tech is growing bigger every day. It is important to say that not everybody thinks this is a problem. However, it seems like there is a consensus among democratically-elected leaders in both the U.S. and Europe that the influence of these companies must be reined in. The U.S. and the European Union recently agreed to take a more unified approach in regulating big technology firms. In fact, even the people who work in the industry share this view. In a survey of 1,578 tech employees made by Protocol, 78 percent said that Big Tech is too powerful.

So, what can be done? A variety of options are already on the table, from forcing companies to break up to altering laws that give social media companies a free pass compared to traditional media. If the New York Times publishes hate speech they are liable, when Facebook does the same, they are not. In the US, this legislation is referred to as “Section 230”, and there is a debate around whether to change it. At the same time, numerous lawsuits have been filed around the world against the Big Tech-companies on anti-trust issues. The stock market has sent the message that the idea that any of these measures could seriously harm these companies is simply unfounded. And that view could very well be justified. There are several reasons why Big Tech-titans can sleep well at night. Let’s run through some of them.

Breaking up is almost impossible

The businesses of Big Tech are deeply interconnected. It would take years of litigation to make such a decision a reality. With 300 billion dollars of annual profits, the legal coffers of Silicon Valley are limitless.

Fines would have to be astronomical to make a difference

Between 2017 and 2019, the EU slammed Google with a total of eight billion USD in fines. That is less than seven percent of the company’s pre-tax profit during those three years. As the stock market often regards fines as a “one-off”, it is not clear if even larger fines would hurt the market cap at all.

Too drastic of measures could trigger a stock crash

In theory, politicians could of course make new laws that severely hurt Big Tech. This would very likely lead to correction of their stock prices, which in turn would weigh heavily on the start-up ecosystem and the economy at-large. To have voters lose trillions of dollars, or even worse their jobs, is not a price any politician is willing to pay.

The companies could fight back

This is the most underestimated scenario of all. What if Google eliminated negative news stories about Google from searches, or they monitored Gmail and Google Docs to stop whistle-blowers or investigative reporters?

What if Facebook took down the accounts of politicians who are critical of Big Tech? What if Youtube only recommended documentaries that showed how fantastic Silicon Valley is for humanity?

This might all seem rather dystopian, but the question must be asked. After all, anything that can be done with technology tends to be done. With Facebooks “Project Amplify”, this is already inching towards reality. Most importantly, what could anyone do to prevent this? The answer is: nothing.

As things stand now, Facebook and Google are controlled by Mark Zuckerberg and Larry Page/Sergey Brin who own more than 50 percent of the voting power. An American president can be thrown out of office, but no one can sack Mark Zuckerberg. And the reality is that Big Tech can use the power of their platforms for more or less any purpose they please. As Facebook whistle-blower Frances Haugen told CBS 60 minutes:

“The thing I saw at Facebook over and over again was there were conflicts of interest between what was good for the public and what was good for Facebook, and Facebook over and over again chose to optimise for its own interests, like making more money.”

To satisfy Wall Street, Big Tech-giants must deliver constant growth and more profits every year

Here we arrive at the crux of the problem. Silicon Valley’s algorithms govern the world, but these giants are in turn governed by an even more powerful algorithm: the paradigm that is called shareholder value.

To satisfy Wall Street, Big Tech-giants must deliver constant growth and more profits every year. And in the choice between ethics and profit, the answer is, more often than not, profits.

Silicon Valley author and entrepreneur Tim O’Reilly has called Big Tech “slaves under a super-AI that has gone rogue” – meaning the financial markets.

Breaking out of this cycle is easier said than done. Companies like Apple, Google and Facebook use their stock to pay their employees, which means they are highly dependent on stock prices rising.

But bad ethics also runs the risk of alienating these same employees. Internal protests have rocked Google, Amazon, and Microsoft in recent years.

Hurt society or hurt the stock price? Lose staff over scandals or over bad pay? These are the dilemmas that the most powerful companies in history face. Whether Big Tech has really become too-big-to-stop remains to be seen. Ultimately the power rests with you. Without the billions of daily users, Silicon Valley’s influence amounts to exactly zero.

So, if your kids or grandkids one day ask how a few individuals acquired so much wealth and power, the answer is simple: we gave it to them.

Andreas Cervenka

Columnist, Aftonbladet

Years in Schibsted: 10 years at SvD (2007– 2017), at Aftonbladet from December 2021.

Meet our people: Let all people blossom

Meet our people

Julie Schoen’s company DBA has recently joined the Schibsted family, Sanni Moilanen works for our Finish marketplace Tori and Håkan Halvarsson is our new head of People & Culture. Get to know them and what they do.

Let all people blossom

One comment has haunted Håkan Halvarsson more than any other. Growing up, he was often asked: “Why do you always need to go against the flow?” Ever since, it has been clear to him that this is probably the most important thing he can do.

“My mother taught to always question given things.”

Perhaps this thinking will infuse Schibsted – as Håkan’s new assignment is to develop leadership and culture across the company. It’s not exactly a straightforward task in Schibsted, since it consists of many strong and independent brands, each with their own identity and culture.

“The pressure to be a modern and attractive employer has increased enormously. Not least has the pandemic fast forwarded us by 15 years with new ways of working, which is truly creating a global work force. Schibsted’s strength is that we are stronger together.”

In Håkan’s mind the key to fully acting on this advantage is through leadership. And building a common, overarching leadership culture is now high on the agenda. One step on this journey is the recently launched Harvard program in disruptive innovation.

“We also need to build our culture around how to find failures, catapult learning and optimise solutions. Failure is a great force if harnessed well. That’s how innovation happens.”

Going back to that comment about going against the flow, Håkan is also on a personal crusade to promote everyone’s uniqueness as a strength.

“When I think institutions in society, my impression is that they are made to crush uniqueness because it’s simply irritating. If our leaders and our culture could instead view individual uniqueness as a strength and let all people blossom to their full potential, I’m convinced that more success will come to all of us!”

Håkan Halvarsson

SvP People & Culture

Years in Schibsted: 10

Finding unknown treasures

Nice and engaging storytelling is great for inspiration and an effective marketing tool.

Julie Schoen has been working at DBA (Den Blå Avis, the Danish marketplace that recently became part of the Schibsted family) since 2017, and she and the marketing team have taken the idea of telling stories to the next level.

“When I started to contact sellers behind interesting ads, asking them to tell their stories – the effect and the engagement grew, it became a success.”

Today the DBA Guide is now a full site with stories about things for sale, tips on how to “upcycle” used things and guides on how to get your stuff sold. One of the most popular video concepts is about collectors.

“We focus on ordinary things that most people have at home, like puzzles for example. It’s great to show that things you might have in your basement can actually be worth some money.”

For other stories, Julie meets up with people who are selling more unique things, to create entertaining articles and videos, and to show people what they can do with reused things.

“It’s also nice to demonstrate that sellers and buyers are just ordinary people, like you and me. Sometimes people worry about meeting people they don’t know.”

Julie Schoen

Editor DBA Guide, spokesperson DBA

Years in Schibsted: 0.5

Supervisors will build the culture

When Schibsted bought Oikotie, there was a need to create something that could bind the company together with Tori – the other Finnish marketplace owned by Schibsted.

Sanni Moilanen, and the rest of cthe people team in Finland, began looking into a new kind of managerial role, to serve as an enabler for creating a strong united culture, for all 180 employees in the two different companies.

“We needed to build something from scratch that could give us a common foundation”, Sanni explains.

The idea was to define a role that would focus on people, coaching and leadership, instead of functional responsibilities, a concept that Sanni found so interesting that she decided to write her master’s thesis on how to define it – a role they ended up calling “supervisor”.

“The purpose of our supervisor is to empower employees to reach their full potential and to support a more modern way to lead. And we are convinced that this will lead to an innovative culture.”

The role is still new but it has already brought managers together. The onboarding included a “Supervisor Buddy” system in which two managers met and discussed the role regularly. And Sanni is quite happy with the results.

“I believe this is the first step towards our goal of creating a true learning organisation.”

Sanni Moilanen

Learning & Development Manager

Years in Schibsted: Almost 6

I believe it can fly

I believe it can fly

The world’s tech investors are turning their attention to electric planes; but are battery-powered engines enough to get airline companies up and flying again?

But first, let’s get the cultural reference out of the way: R. Kelly believed he could fly, and for a while he did. But he flew too high and ended up a dark hole he won’t be coming out of any time soon. Many of the companies which are currently flying high on promises of electric planes will suffer a similar fate.

Electric aircraft may seem a long way off right now, but things can move fast in the world of technology. No one could envisage a world without air travel, either.

A life-threatening virus and closed national borders knocked the wind out of the airlines. Some of them hit the canvas, while others clung to the ropes and tried to stay on their feet despite feeling groggy and confused. Their revenue streams were cut off, and no matter where you build your levee, water will always find a way. Virtual meetings and advanced presentation tools aren’t actually that new, but the pandemic struck at the same time as these technologies matured. Bit rates have now become good enough, so public and private enterprises – and people generally – were now forced to take a giant leap into a new reality, with communication technology which otherwise would have been lightyears away. They discovered that in most cases they didn’t need to fly at all.

And then came the reports concluding that we should do whatever we could to avoid flying.

Several alarming climate reports from the UN are causing passengers to lose sleep at the mere thought of helping the airlines to stay afloat.

A negligible proportion of the world’s population flies frequently, yet air traffic accounts for around 2.4 percent of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. On top of that comes emissions of nitrous oxides, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and soot. An EU report from the end of 2020 confirms that the combined impact of these emissions is at least as serious for the climate as the CO2 emissions alone.

Some airlines are trying to put lipstick on a pig by bragging how fuel-efficient their planes are.

Some airlines are trying to put lipstick on a pig by bragging how fuel-efficient their planes are. And to some extent they’re right; modern passenger planes use way less fuel than they did 20 years ago. But they still use a lot of fuel. And before the virus took off in Wuhan, people travelled way more than they did back then. So, emissions have not dropped over time; they’ve risen dramatically.

Everyone realises that the aviation industry needs to cut its emissions – for moral as well as economic reasons. Many countries have now adopted political strategies to dramatically cut emissions from air traffic in the coming decades. The first airline to offer passengers a climate-friendly, quiet plane – and a good conscience – will laugh all the way to the bank. You only have to look at the auto industry. Part of the reason why investors have money burning a hole in their pockets is that they missed out on Tesla.

A wonderful experience

It just so happens that, at the time of writing, I’m driving a Tesla all over Italy. There are still very few electric vehicles here (and the further south you go, the fewer you see), and the Model S, which is now a common family car in Norway, attracts as much “attenzione” in Italy as a Lamborghini Aventador. Besides, it’s a wonderful experience to move silently through the vineyards with the top down in the low yellow light before darkness falls. And the absence of a cloud of exhaust fumes trailing behind me makes it all the more beautiful.

The future of the auto industry is electric. There’s no doubt about it. Even the present is electric. But somewhere in the mountains in Abruzzo I discovered an uncomfortable truth: the amazing power of an internal combustion engine. There are still some areas where the electric vehicle is outdone: with a petrol-powered car I could have avoided spending endless hours at charging stations; I could have chosen other routes; and I could have driven to out-of-the-way places that lie far beyond the reach of any charging station. I would have avoided having a tiny heart attack from having just about enough battery power to reach a charger but making a wrong turn at a traffic circle and ending up on a freeway heading in the wrong direction.

But things could have been worse. I could have been flying a plane.

Here’s my theory: the further you are from the ground, the greater your range anxiety. If my Tesla runs out of power on a roadside somewhere in Tuscany, theoretically I’ll have time to down a bistecca and glass of a decent Brunello while I wait for roadside assistance. If a plane runs out of power at 20,000 feet, theoretically I’ll have time to say a short prayer before it’s all definitively over.

The apparently insurmountable problem is that the need for more battery capacity increases exponentially with the distance from the ground. Moving a plane carrying cargo and passengers from one place to another demands a colossal amount of energy.

Heavy as lead

In an ideal world, the airlines would simply have replaced the fuel engines in an already approved plane. It would be faster, cheaper and simpler than going all the way back to the drawing board. But it’s not that simple. Electric engines require batteries which (currently) are as heavy as lead. A plane that is approved with an engine weighing, let’s say, one ton with a full fuel tank, would not be able to fly with an electric engine that weighed ten tons with batteries. So, to reduce the weight, you would need to reduce the battery capacity – and consequently the range.

This is what’s giving the industry its biggest headache right now. If enough batteries were crammed into a Boeing 737 to make it possible to fly from London to New York, the plane would be so heavy that it would sink into the runway rather than take off from it. Nor would there be any space for passengers or cargo, which would make the whole exercise pointless anyway.

Big electric passenger planes will therefore not be a reality until the batteries are made considerably smaller and more efficient. We will get there sooner or later, but even the developers says we’re at least a couple of decades away – unless, that is, stopping over 30 times between Stockholm and Rome becomes a viable business model. But this doesn’t mean that electric planes are a bad idea.

Some of these developers may well succeed, but many will be kept afloat by tall tales and naive investors

Loads of companies are now working on developing electric aircraft. Tiny helicopter-like vehicles that can be used as taxis or delivery vehicles are generating the most hype. Many of them look ultra-cool, resembling the futuristic drawings we did in elementary school in the 1980s, with people wearing silver clothes, eating pills instead of food and whizzing around with jet packs and flying cars.

Some of these developers may well succeed, but many will be kept afloat by tall tales and naive investors. Many have already failed, and more will follow. The most exciting and promising developments are happening in the more conventional part of the aviation industry. Only once passenger planes become electric will they really take off.

Two trends stand out

SAS is collaborating with Airbus, United with Swedish startup Heart, and Easyjet with the American startup Wright Electric, and so on. Most of the airlines are desperate to get an electric plane into the air because it could prove profitable – and sooner than you might expect.

If you compare today’s aviation industry with that of the 1980s, two trends stand out:

- The regional airports are increasingly underused.

- The airlines are flying bigger planes with more seats.

These trends are driven by the fact that the cost of buying and maintaining an aircraft engine is roughly the same regardless of size and trip distance. This makes small passenger aircraft for short routes less profitable. In the 1980s, the average number of seats on regional flights was 20, whereas today it’s 80.

This does not necessarily favour the interests of passengers; they have to spend more time and money on reaching the large airports, they depart from somewhere far from home and land somewhere far from their final destination, and do so in huge, noisy and polluting planes.

Regional flight might be profitable

Investors and founders of companies like Heart and Eviation in Israel claim that the cost of buying and maintaining an electric engine is a fraction of the same cost for a fuel engine, and that electrification can therefore make regional flights using small aircraft profitable again.

In September Rolls-Royce completed a successful 15-minute flight test in “Spirit of Innovation”, an all-electric aircraft in the south of England. The aircraft only has one seat, but the experience gained will be used to develop a passenger aircraft.

Tecnam in Italy is hoping to have an all-electric aircraft with a capacity for nine passengers in the air in 2026, complete with a Rolls-Royce engine. Norway’s Widerøe has shown an interest, since a large proportion of its flights cover short distances in northern Norway. The range at the time of launch will be around 200 kilometres. Heart Aerospace, which is based outside Gothenburg in Sweden, is working on an electric plane for 19 passengers. The range at the time of launch will be 400 kilometres.

Sceptics would dismiss these performance properties as ridiculous compared to fuel aircraft, in terms of both passenger capacity and range. But here’s the interesting part: 400 kilometres is enough to cover around 80 percent of the routes in markets like those in the Scandinavian countries. Other interesting markets for this type of aircraft include island-hopping in countries like Indonesia, Greece, Japan and the Philippines, or indeed any country with mountain ranges or lakes that take a long time to traverse. Or for moving troops and crews. Air ambulance services. You name it.

This summer, the American airline company United placed an order for 100 of these aircraft with Heart.

Severe economic impact

It’s happening now … or soon will be, at least.

As we know, the aviation industry was hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. Few people wanted to travel, and those who did were not allowed. The airlines’ revenue streams dried up, and orders for new aircraft and engines were cancelled.

The economic impacts were severe. Rolls-Royce lost 4.5 billion USD in 2020, and had to cut around 7,000 jobs to save money as well as make some tough priorities in other parts of its operations. This will likely delay deliveries of new engines by several years, which in turn may create delays for Tecnam and Widerøe. So the chances of sitting in an electric plane any time soon are slim, though it may well be a reality by 2030.

In the meantime, see you on Teams.

Joacim Lund

Technology commentator, Aftenposten

Years in Schibsted: 16

Uncertainty is like driving on an ice patch

Amy Webb and her Future Today Institute team has helped Schibsted isolate six trends that the company needs to lean into. Photo: Emil Wesolowski

“Uncertainty is like driving on an ice patch”

How do you face the uncertainties of the future without a crystal ball? You analyse data and you prepare as best as you can. In the Horizon project, Schibsted is doing just this together with the Future Today Institute and its founder Amy Webb.

The Horizon corporate strategy project was created with the purpose of creating a common understanding of mega-trends shaping Schibsted future in five to ten years and rehearsing multiple futures through plausible scenarios. The project was created by Schibsted together with Tinius Trust/Blommenholm Industrier and the Future Today Institute, to make Schibsted better equipped to succeed – regardless of how the future develops.

Futurist Amy Webb and her team at Future Today Institute have worked closely with Schibsted’s Anders Grimstad and Zuzanna Zyglado-Stenberg to create a plan for whatever the future may hold.

Webb explains this work as looking for signal data early, thinking about what that might mean and starting to model alternative futures that describe next-order actions.

Slowing down the process of change

“There’s an analogy that I like to use to describe what this process is like. I’m originally from Chicago in the United States, where there is a ton of snow, lots of ice, lots of wind – it gets very, very cold”, Webb says, something her hometown has in common with the Nordics.

In both places, anyone with a drivers license needs to learn to drive on ice. She says this moment that we’re living through, with uncertainties in business, regulations, environment and regarding the pandemic, is very much like being in a car sliding around on ice.

“When you’re driving, and you’re hitting an icy patch, at that point, your limbic system starts to take over. You get really nervous and you start a lot of super-fast, haphazard decisions.”

She explains that your brain believes that if you slam your foot on the break right then, the car will stop. But that’s not the case. Slamming your foot on the break will just cause greater problems. So what do you do instead?

“You’re supposed to steer your car into the direction that you’re sliding. That feels wrong in the moment, but as you know, if you keep your eyes on the road further ahead, what steering into the slide does is it slows down the process of change.”

That’s what we should be doing right now, in business as well, even though it feels wrong, she says. We should be leaning into uncertainty.

“I think it’s all about recognising those uncertainties but also exploring the white space. Where are all the possibilities for Schibsted to grow in ways that you just haven’t thought of before?”

Created clusters of trends

Starting this project, the Schibsted team, together with FTI, created baseline futures based on interviews with the top stakeholders and leaders. Ironing out where they agree and where they disagree on what the world will look like in five to ten years allows them to see where our uncertainties lie. From there, FTI was able to look into their data to see which trends coincide with Schibsted’s interests (look into the six overarching trends here).

With trend clusters in place, FTI is now ready to create future scenarios, being the next milestone in the Horizon project. A key thing to bear in mind when looking into the future, though, is that it’s not as far away as you might think. Preparing for tomorrow means acting now, creating a plan for next year with a ten-year perspective, or even six months ahead, but always with a long-term perspective in mind..

“There’s already a case where Schibsted saw the challenges of the future and acted in time to change and grow”, says project co-lead Zuzanna Zygadlo-Stenberg, referring to establishing online classified at the beginning of 2000s with Finn.no. At the time, Schibsted was a media company faced with the uncertainty of what what the future promise of the internet might hold.

“We managed to adapt, build marketplaces and take a position in a new space and become profitable. Understanding the great forces, how to use them to our advantage and create growth”, Zygadlo-Stenberg concludes.

Camilla Buch

Advisor Editorial Content

Years in Schibsted: 1.5

Enter the Metaverse

Enter the Metaverse

Facebook is hiring 10,000 people to work on it. The Metaverse is no longer science fiction – some say it’s the next Internet.

Throughout the last few decades, much of what we previously considered science fiction has become more science than fiction. We may not have flying cars yet but asking your fridge to create a grocery list is an everyday occurrence. And – as has been stated so many times before – our precious smartphones have more processing power than NASA did when it sent Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the moon. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to us when terms like “the metaverse” are no longer constrained to The Matrix and Ready Player One. But before we look at how the metaverse will impact our future, let’s understand it.

A futuristic virtual world

The term “metaverse” was coined by author Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel “Snow Crash”. He used the term to refer to a 3D virtual world inhabited by avatars of real people. The term comes from “meta” (beyond) and “verse” (from universe), and it is typically used to describe a futuristic virtual world on the internet in some form. Still, the term, as it pertains to an actual, real-world phenomenon, doesn’t really have a universally accepted definition.

Venture capitalist and author of “The Metaverse Primer”, Matthew Ball, writes that “The Metaverse is best understood as ‘a quasi-successor state to the mobile internet’”. This is to say, it’s a technology that will completely change how we operate in the world but also take a long time to develop based on many different, secondary innovations and inventions.

Since metaverse is not a completely developed term with a clear definition, it’s tricky to pin down, but I’ll give it my best shot. Currently, as far as we can define it, the metaverse looks like a successor to the internet in which its users are more tangibly connected to the virtual experiences taking place there. That could be via everything from voice interfaces, to VR headsets and haptic wearables.

We’re already unlocking our phones via facial recognition and buying digital art via non-fungible tokens.

In the long run, it is believed that all of these experiences will be connected and collected in the metaverse, just like the internet is the collection of a vast universe of 2D websites. The Verge has broken down the parts of the metaverse that most excite the tech industry right now, things like “real-time 3D computer graphics and personalised avatars,” and “a variety of person-to-person social interactions that are less competitive and goal-oriented than stereotypical games.”

Previously mentioned author Matthew Ball believes that the metaverse will have as big of an impact on our daily lives as the electricity revolution and the mobile internet. It’s also an interaction of the same kind – the internet (and its iterative version, the mobile internet) couldn’t have happened without the electricity revolution, and the metaverse couldn’t happen without the internet.

Ball writes that the “metaverse iterates further by placing everyone inside an ‘embodied’, or ‘virtual’ or ‘3D’ version of the internet and on a nearly unending basis. In other words, we will constantly be ‘within’ the internet, rather than have access to it, and within the billions of interconnected computers around us, rather than occasionally reach for them, and alongside all other users and real-time”. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who is a big proponent of the metaverse, has described it as “an embodied internet”.

10,000 new workers

His plan is to shift Facebook from a social media company to a metaverse company, and he’s already put this plan in motion. The company will change its name – the social network will keep Facebook but the parent company will be renamed, much like Google’s approach with its parent company Alphabet. This could be to avoid the less than stellar reputation linked to Facebook, but it also symbolises the shift in course. Zuckerberg plans to employ 10,000 new workers in Europe to join the company’s components and create this metaverse.

Now, that all sounds very sci-fi. But it’s really just the next step in the development of things we already take for granted. We’re already unlocking our phones via facial recognition and buying digital art via non-fungible tokens. Admittedly, it feels more far more far-fetched that we’ll be having our team meetings remotely via VR setups, sitting on our couches at home while appearing at a conference table in a virtual space with our colleagues.

Independent tech analyst Benedict Evans explained the current discourse around the metaverse like “standing in front of a whiteboard in the early 1990s and writing words like interactive TV, hypertext, broadband, AOL, multimedia, and maybe video and games, and then drawing a box around them all and labelling the box ‘information superhighway’”. Essentially, we’re merging tech and concepts such as augmented reality, virtual reality, mixed reality, gaming, cryptocurrencies, non-fungible tokens and more, under one umbrella.

Connectivity is the key difference

I’ve started thinking about the theory of the metaverse like electricity. The idea is that we’ll be using it so naturally in our daily lives, when swapping our glasses for AR glasses with interactive screen overlays, that we don’t even think about it unless it goes down. As I mentioned before, we already use an extended internet, in which our physical bodies, voices and gestures are connected to our devices (think face scans, voice assistants, and VR). The metaverse is the extension of this. Perhaps we’ll all have virtual avatars representing ourselves online, for which we buy virtual designer clothes and virtual bespoke art pieces with non-fungible tokens.

The key difference between that and what we have today is connectivity – between ourselves and the virtual world, and between the many different existing virtual worlds. Especially following the giant disruptor that is the Covid-19 pandemic, the need to physically engage with other people is huge, but so is the need to connect with people over vast distances in just a matter of seconds. The metaverse could be a merging of the two needs.