We have all the opportunities we could dream of

We have all the opportunities we could dream of

We are facing a new reality. As a company, as human beings, as parents of the iGeneration, and as global digital consumers. Where fake news seems to travel faster than truth on social media, where reliable sources of information are being greatly challenged, where authoritarianism and populism are growing, and perhaps most worryingly, where our way of life is disrupting Earth itself.

It is also a reality where a few global companies are dominating, not only businesses, but also peoples’ daily life. On the bright side it is an era where we have all the opportunities we could ever dream off. More data and knowledge than ever before – paving the way for extraordinary achievements and discoveries. Science and medical treatments are improving rapidly, finding new cures and amazing ways to save, improve and even drastically prolong lives. But how do we meet this new world?

When I left Aftenposten in 2010 the digitalization of media was just in its early days. Returning today as CEO of Schibsted, the landscape and conditions are drastically different for both our media, marketplaces and growth companies. We all know that technology is crucial for our survival. But so is our heritage that stems from a free press, transparency and entrepreneurship. In the world that we navigate today, the role Schibsted has in society is crucial. Which is also one of the reasons why I was inspired to come back.

In the end it’s about our customers. And that we are able to meet their needs in a sustainable and trustworthy way. Not the least when developing our platforms for secondhand trade. If even more users see the benefits of these marketplaces, we have all contributed in a very concrete way to a circular economy and a more sustainable world.

Poio makes learning into a game

Poio makes learning into a game

Daniel Senn is the dad, the educationalist and technologist behind Poio, the reading game that is helping thousands of Norwegian and Swedish kids to crack the reading code while playing.

The company launched its first reading game in Norway in 2017, then in Sweden 2018. But the story of Poio takes us all the way back to 2012, the year when Daniel had a son with impaired hearing. This story is about a father who decided to turn a challenge around and make it a solution for tens of thousands of people. Impaired hearing is one of many reasons why children experience difficulties in school. Learning to read is one of the first tasks confronting a pupil. It becomes the foundation for most of the learning that awaits them, and demands a lot of repetitive training. As Daniel talked with scholars and people with similar experience, they confirmed what he had suspected: that learning to read can be exhausting to a child. That struggling with learning can, over time, create negative learning spirals leading to serious consequences.

“I decided that my son was not going to have to go through that. There had to be a way to do something about the learning methods! To create a positive form of learning. On Leon’s terms. So we could avoid him reaching a point where he associated learning and reading with something negative”, says Daniel Senn. After a lot of searching with no results Daniel decided to try to solve the problem himself by working with things that Leon liked. It was going to evolve into an entertaining digital game full of funny characters and exciting missions. But the first prototypes of Poio were made with cardboard, paper and scissors at home on the kitchen table. “In the beginning I played with characters, letters and words together with Leon and his older brother Aksel to see what caught their attention, just with simple methods. One cardboard game that I made together with them turned out an instant success. It was one where the children had to figure out which objects/words the Vowel Monster could “eat”. They wanted to play it again and again. It was fascinating to watch how eager they were to master the game and learn new letters and words”.

The road from cardboard figures at home to a digital game started for real in 2015. With the cardboard game as a starting point, a long journey towards developing a more advanced digital prototype began. Daniel had worked on many digital learning games but could not find the equivalent tool for reading training. This led to the family making a choice: Daniel was going to quit his job and together they would put their efforts into making a universal reading game of high educational standard. “I felt an incredible drive to combine all the things I had learnt about game development, teaching methods, communication and aesthetics in order to create something meaningful. Something that could help children in a crucial phase of their development. Not only for my own son but for all children and families who meet challenges with reading training, regardless of age and preconditions.

“We hear that Poio is part of the reason that they are now reading their first book.”

It felt a little shaky to move from a safe and good job into the unknown. But it was a choice we made together, as a family – a choice we have never regretted.” In this project, an essential role has been played by Daniel’s co-founder and game developer Johannes Stensen. “A critical component for the success has been that the two of us have had the skills to develop the reading game on our own with a high degree of confidence in each other, a childish urge to experiment and a willingness to change the concept as we went along and learnt new things. At the same time, we have had a large network of people – including children – who have wanted to help us free of charge.” In order to learn more about how to evoke positive motivation in children, the two have been working closely with educationalists, teachers, professors and other parents. This has helped to ensure good quality content and find methods that could be combined with elements in the game.

“If they have fun, they will learn”

“Poio is a result of assistance from a large number of knowledgeable people who have contributed with their special competence, experiences and good questions throughout the whole development. Furthermore, they have given us the necessary confidence to challenge established truths about the best way for children to learn to read and confirmed what our guts were telling us: that curiosity, excitement and making reading joyful, are the keys to success”. They have also met several people who have had doubts about using digital games for educational purposes, particularly since Poio has many similarities with commercial entertainment games, where there are few specific instructions and the children have to figure most things out by themselves.

“This is one of the main points. For children to spend time on playing Poio it has to be built like that, on children’s own terms and as a real competitor to what the children are already spending a lot of time on. The children themselves must become fascinated by the challenges and feel that they want to learn more, both about the game and about our written language. And on top of that; if the children are having fun they will learn much more”.

At last, in the summer of 2017, they could share the reading game Poio with every family in Norway. The launch exceeded all expectations. “The road from our own small family project to a full national launch has been quite incredible. And the need for new tools for learning is clearly big”. They receive feedback every day from parents telling them how their children have been struggling trying to crack the reading code. ”We hear that Poio is part of the reason that they are now reading their first book. That is a fantastic feeling. Our goal is that no child should struggle with cracking the reading code. Some people might find that an unrealistic goal, but I just don’t listen to them”, Daniel says.

Poio has become a huge success already during its first year and families all over the country have confirmed what Daniel hoped for. The game engages the children and makes them eager to read, regardless of background. A year later the game now is also available to families in Sweden. Next year, Poio will be moving on to other places in the world.

Leon just started school

And for those of you who wonder how Leon is doing: he just started school this fall. Now Daniel will find out how the family’s joint project has affected Leon’s reading development. “Leon’s language is now developing in a way that is perfectly normal for his age. And he is very close to cracking the reading code. We are looking forward to his first year at school and we are absolutely confident about his future development, because he thinks learning is fun. Just like it should be for every child”, Daniel says. And what does Leon like most about the game? ”I like that the characters are so different and to steal the letters and get away with it”, he explains. He is also super proud for giving voice to Otto – the pink rabbit with a beard and large fangs.

Subscribers support a free press

Subscribers support a free press

Netflix and Spotify proved that you could get paid for online content. Other businesses are following – not least the media. In Schibsted over 1,100,000 people subscribe to one of our newspapers – 65 percent are digital only. Having subscribers, in addition to advertisers, pay for your work means you can focus more on in-depth pieces instead of writing articles mainly to generate page views. It also makes the business model more robust.

Secure independence

But acquiring digital subscribers is expensive, especially when many people still attribute greater value to the print product. And within a few years there will likely be a natural market cap in volume and in revenues. To secure media independence in a climate that is indifferent to or hostile towards mainstream news is another crucial challenge when, at the same time, there’s a major technological disruption to the income streams. To succeed in this, we believe in having a consolidated consumer business unit that is closely aligned with product and editorial.

We have to clarify our brands

We’ve identified five areas that we will focus our attention on: Our news brands are our greatest assets. They have been built by providing decades of high quality reporting that people trust. But in a world where we’re addressing consumers, we have to clarify our brands, to help people choose us. Bundling is an avenue worth pursuing. Business financial news from all our brands might for example be an enticing prospect. Creating a portfolio that allows for rich bundling and flexible payments is crucial. Many people value discoverability and curation above all else. We need to create the kind of premium subscriber experience that evokes real desirability.

Much work is to be done

The more data driven we become, the better we optimize the consumer business. We still have huge potential in automating our prospecting, sales and anti-churn efforts. There is also a lot of value to be created outside our editorial products. This is done by many today by offering loyalty programs. We believe we can scale and professionalize a lot of these offerings. Much work is yet to be done, but we’re going into this uncertain future with our eyes open. We believe we are on the right path to finding new models that our businesses can rely on, in order to safeguard the future of a trustworthy, free and independent press.

Tor Jacobsen

Sidney Glastad

How to get paid

How to get paid

What kind of journalism are the readers willing to pay for? At Svenska Dagbladet, this question has led to new priorities and ways of working. The answer has made it clear what news media should concentrate on: meeting readers’ demands and devoting ourselves to journalism.

Do you think that one cannot predict news journalism? Well, in September, 18 years will have passed since the terrorist attacks in the US, and just like before the media in Sweden, as well as in the rest of the world, will produce articles about 9/11. In a generally unpredictable news flow, editors are grateful to be able to plan something that won’t change, regardless of what else happens. But new possibilities of data analyses are merciless towards old editorial habits. So far, I have not seen one single piece, where the anniversary has been the gist of the story, that has actually been read by any significant number of people.

The same thing goes for what we in the newsroom call “Wikipedia pieces” i.e. articles that too closely resemble encyclopedia entries or something that government authorities might post on their websites. Under the category “Why not?” we count articles that often are a combination of a not very thought-through idea and a stressed subeditor. The result is lukewarm content lacking relevance for a majority of readers.

What would readers pay for?

All three of these categories have now been banned in the SvD newsroom. They may seem harmless but they occupy way too much resources and are literally in the way of the kind of journalistic work that engages readers. A bit more than three years ago we started the project SvD Premium – content only for subscribers. At the time we did not ask ourselves which parts of all our journalism that we were going to lock in. Instead we started at the other end: what content could be so relevant that the readers would be willing to pay for it? Judging from thousands of converting articles in different formats and in different topic areas, we could soon see a pattern. The common denominator was not topics but needs. A model with four fields took shape:

1: Content that is helping the reader understand the news flow

For media houses in the news category, this is fundamental. Without an astute journalism that is investigating, digging, guiding and analyzing the news flow, the whole model will collapse. This is a field that delivers a great number of articles and has many readers. The rate of conversion is rather low, as other media can present similar content, but the volume leads to a high share of new subscribers.

2: Content that is close to the readers in their daily life

This can best be described as journalism that the readers “need to know” and is useful in their day-to-day life. For example, it can be advice concerning people’s private finances and property deals or new findings in psychology, food or health. This field has many readers and a high rate of conversion.

3: Content that is helping the readers understand the world we live in

This is about our own takes, describing something about the wider world around us – where the society or parts of the population are going. For example, at SvD we have had a great success with in-depth reports on how Sweden would look in the year 2025 if the right-wing Sweden Democrats, or other political parties, were to decide. It could also be reports from worlds that most readers cannot reach, such as a piece from inside Mensa, the association that gathers people with a high IQ. The number of readers is often lower than in the other two fields, but the rate of conversion, among those who take an interest, is high because the material cannot be found elsewhere.

4: Content close to readers’ interests and identities

“Nice-to-know journalism”. It could be tips about films or books, restaurant reviews, language or history. Normally, this field does not convert very much, but it has a high proportion of logged-in reading and is therefore fundamental for preventing churn. Whenever we have good numbers – for both conversions and engagement – they often coincide with having filled all four fields with sharp and clear journalism in our core topics.

The insights we have gained along the way have, among other things, led to new jobs in the newsroom; editors responsible for different fields in the model, working across boundaries with every other department and in close cooperation with the data and analysis team. Furthermore, we have presented content we haven’t had before, signed on several external people and begun cooperating with other media, such as the American magazine The Atlantic, from which we publish, every month, a carefully selected in-depth story. The efforts have paid off. In the last three years, the number of new subscribers has become almost five times higher, the logged-in reading has gone up as has the conversion rate. As for our prioritized weekend in-depth pieces we have eliminated almost all of the articles that were being read by few and more than doubled the feature stories that engage a large number of subscribers. Both extremes are important to follow up – the editorship of the future is as much a question of editing out as it is of prioritizing.

Readers want to pay for quality

In the present transformation of the media business, the possibilities for working in a data informed way are a good help. The fact that the power now so manifestly has shifted to our actual employers, the readers, may make some people feel uncomfortable: where will it end if we give the readers what they want? Isn’t there a risk that we abandon the role of editors and become populistic? For my part, I am hopeful. We see how readers want to pay for quality. The technology and the way we report may change a lot in the time to come. As long as we focus on what makes us unique in the enormous flow of information, proper journalistic endeavor, the demand for what we do will prevail.

Brands are built to influence

Brands are built to influence

The role of brands has fundamentally changed in the digital era. It’s not all about getting attention anymore, but about influencing peoples’ behavior. But to succeed in this takes trust – something many big brands of today are struggling with.

Who influences you the most? Family you might say, then friends, or colleagues? Probably also people who represent political, religious or other values that are important to you. People you admire? Would you have mentioned companies and the brands that represent them? If not, let me state my case for why you should have. Chances are that from the moment you wake up and reach for your phone until the last episode you stream before bed, businesses influence more choices in your daily life than any living, breathing person. Many of the everyday decisions you make have been effectively outsourced. A frightening thought?

For example, your social media curate your feed and thereby influence what you experience of the world. Your media outlets choose the news they deem most important based on your editorial profile. Services you use throughout the day – whether Slack or Starbucks – nudge, suggest and direct your actions and attitudes. Linkedin and Tinder even influence who you build new relationships with. Your life is shaped by the habits they induce, and the recommendations and the choices they make on your behalf. Consider the influence of tech companies that have fundamentally changed the way we live, work and play. It’s difficult now to even imagine a world without brands like Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon, Airbnb, Uber, Netflix, PayPal or eBay. They simply make everything so convenient. These brands not only influence us as customers and users, they introduce and disrupt entire categories.

New categories emerge and for each new category the brands’ main task is to influence our behavior towards adopting the behavior of the category, rather than seeking to influence preferences between brands in the category. When Alipay gets a staggering number of people to invest small amounts of their savings, you get the phenomenon Yu’e Bao, the world’s largest money-market fund that has traditional bank heads spinning. When Spotify gets people to subscribe to all music month by month rather than buy one record for forever the whole music industry is shaken to its core. Behind these successes is the fact that the brands know a lot about us and are willing and able to use that knowledge to create “sticky services”. Sometimes it’s a great idea realized. Other times it’s the business model itself that’s sticky. Most digital businesses have elements of both. You need a business model to realize a great idea, and a great business model will not fly without an idea for people to engage with. All of this has changed the way we now define brands.

Names with the power to influence

In the beginning a brand identified the maker of the pot, the wine or the plough – it was personal. With the industrial age and its faceless factories, the brand replaced the personal connection between maker and user, becoming a substitute identity carrying the promises of products and services. As the number of competitors grew, brands evolved personalities, values and lifestyles to target specific segments, and as a consequence brands became cultural identifiers. The most commonly cited definition of brands in this sense comes from Keller and talks about brands as “a set of mental associations”.

Today a brand is tasked with influencing behaviors in a more fundamental way. Just as brands have extended beyond the sphere of consumer products to include movements, institutions, people and places, a brand’s power to influence must go beyond establishing preference between a finite number of competing products in an existing category. A set of mental associations is simply no longer sufficient. The French brand expert Jean Noel Kapferer has suggested “a name with the power to influence” as the new definition of brand. A brand’s influence can be exerted in subtle ways and may be integrated into the product or service rather than communicated through the traditional means of brand building such as advertising. I’m willing to bet you can’t name the marketing campaign that made you download Instagram or start using Google maps.

Brands and products blur

Since the 50s brands have played out their personality and promoted themselves through the ad, the 30-second spot, sponsorships and similar. This kind of thinking is still very much alive and lately perpetuated by the micro targeting that follows your every click. The exposure traditionally had one goal; create awareness, interest, desire and action (AIDA) for the advertised brand. The customers would – based on their experience, the reputation of the brand, the social status the brand provided, etcetera – decide whether to become loyal or choose a different toothpaste, car or insurance company next time. The product or service brands carried most of the relationship, the companies behind them were less visible (and if they were visible it was mainly to stakeholders like the finance community, governments or their industry).

Today the distinction between the product brands and the companies behind them is becoming much blurrier. New categories often emerge through stories of bold missions undertaken by the founders, and users not only let these brands into their lives, they also act as brand ambassadors and sales reps through recruitment of friends, family and colleagues. Now that we are becoming aware of how intimately these companies know us and how we spend our time, it is no wonder people expect (want and hope for) the “parent” company to be a force for good and not evil.

Close and personal

It is interesting to see how the global megabrands are struggling to address this gap between how effectively they are able to influence us at an individual or product level and how ineffective they have been in exerting that influence as a company when trying to effect, for example, policy changes at the EU level. So far, people either cannot or will not live without the services they have come to depend on, even if they are uncomfortable that the companies behind them are not paying taxes, eradicating local businesses, not having a satisfactory stand with regard to privacy issues and perhaps even criminal business practices and so on. What was once a corporate reputation issue far removed from the everyday branding and sales efforts, has become much more close and personal today as people are starting to grapple with the effects of these issues. This means that brands that seek to establish, maintain and own a lasting relationship of trust with consumers and other important target groups like partners, investors and talent – in order to influence their behaviors – need to bridge this gap somehow.

Visible mother brands

However, people seem to be seeking ways to re-establish the kind of relationships we had to the original maker’s marks, like in the times before mass production. One trend you may have noticed that could indicate that we are indeed craving such a responsible entity is the emergence of visible mother brands such as LVMH or Unilever. These are brands that represent some uncompromising values, purpose or meaningful narrative that permeate all their product or service brands. Over time, people are given an opportunity to get to know, trust and have a sense of loyalty towards the mother brand. The mother brand invests carefully in this relationship, including shared datasets and services, as it introduces and retires brands to and from the family in accordance with that overarching understanding between the brand and people. Take Axe as a case in point. From being the deodorant that magically made ordinary guys irresistible to women, the brand now encourages men to celebrate their individuality, the same way Dove does for girls. Without Unilever’s “sustainable living brands” philosophy the gap between the old and the new Axe could have been too wide for customers to leap across.

A stronghold on behavior

While there is no doubt that the digital megabrands have a stronghold on user behavior, their power to influence authorities and the public at large has shown itself to be limited when it comes to defending their interests. GDPR will make the exchange of data in exchange for convenience much more visible. Public discussions and transparency activists might speed up policy making that shifts the power balance between people and companies back in favor of people.

Since the core role of brands has changed from grabbing attention to influencing behavior, understanding the relationship between people and brands is more crucial than ever. If brands are names with the power to influence, it is time for businesses to stop seeing their brands as marketing vehicles and start using them to create great companies, great products and great societies – all at the same time.

Marketplaces are here to serve you

Marketplaces are here to serve you

Changes in consumer behavior are driving the change in marketplaces. New players will solve narrower user needs, but far more conveniently and smoothly than before. All based on machine learning and data.

Rapid growth in new marketplace models such as Farfetch, Rebagg, Glovo, and Frontier Car Group are great examples of this quick change. These models demonstrate how convenience and flexibility are shaping our attitudes towards spending and how easy it is to switch to a new player in today’s competitive landscape. New marketplaces are moving away from owning unique supplies of goods and content. Instead, by using machine learning and data, they can easily find what we need in a specific niche, where it is available for immediate shipping. This will happen whether we’re looking for a car, for real estate, jobs, home appliances, education or any other segment. This is why there is a verticalization of marketplaces. High relevance is the new black in the market. Medwing is a great example of this in the health area, as is Zenjob for job search, helping students get jobs.

Immersive marketplaces

Usually this kind of approach means higher risk, since it involves handling transactions and logistics, getting temporary workers on the payroll, financing the deal, providing warehousing and relocation services. But the aim is to remove unnecessary friction and barriers to make good deals happen. These new marketplaces do not only sell leads and visibility anymore, they help users to transact and fulfill their needs end-to-end. As an example, a student using the Zenjob app can work whenever it’s convenient between exams, classes and on holidays without the hassle of applying for a job at Zara or H&M. These new models are still at an emerging stage but major VC funds and investors are betting billions to make them dominant in major markets in Europe.

We used to think that you need to build a strong brand to become a destination for certain needs. This still applies, but there is no room for many apps in people’s phone habits anymore. Therefore, we can also see new immersive marketplace models popping up inside mobile apps where we engage on a daily basis. Tomorrow’s winners use machine learning to identify and match patterns in our behavior, learn our purchase intents from P2P communication and integrate themselves seamlessly into communications platforms we engage with every day. We have already seen social network based marketplaces, such as Threads, without a destination site, just living in Messenger apps, and popping up at a relevant moment. I bet these models will appear in social channels like Slack in the coming quarters.

A new era for cars

Car manufacturers are already testing out sharing services based on flexible subscriptions to access a car you need, making it clear that the era of electrical cars will be quite different from the combustion engine cars we know today. There are also new kinds of aggregation services launched for micro-mobility, using bicycles and e-scooters. Behind this is the fact that more than half of our car rides tend to be less than five kilometres. The era of new network based transportation marketplaces has started giving us easy ways to access a vehicle. Mobility companies like Tier, Bipi, Drover and Cluno are great examples in Europe, similar to their US based peers like Uber, Lime and Fair.

The tech needs to mature

The boom of blockchain and cryptocurrencies motivated many teams to discuss how the trust in marketplaces could be solved in a new way. Companies like Listia, Openbazaar and Origami Network have been leading the way and protocols such as INK have collected capital to develop the technology. However, as always the new technology needs to mature and become more scalable to win over older models. But in three to five years time, the development around blockchain will probably pass the threshold of convenience, speed and scalability, making it a viable technology for decentralized marketplaces for mass markets. The underlying blockchain based models will help build highly scalable marketplaces and solve how we transact across different transaction cultures, taxation models and payment structures. It is yet to be seen which protocol will win, but it is evident that the benefits of a fully transparent and trackable marketplace are there.

The lonely team

The lonely team

He had never skied before and his startup was still very young. Still, in May 2018, Thomas Tirtiaux decided to ski across Greenland with four other French entrepreneurs and a guide.

On May 1, 2018 we boarded a bus in Kangerlussuak that dropped us at the foot of the glacier on the west coast of Greenland, at the 67th parallel. Our goal was simple; to cross, in 30 days, the ice desert that separates us from the opposite coast. The challenge was another matter – for six months we had given up everything to prepare for this mythical expedition. For 30 days we would be 100 percent self reliant. There would be no-one to call if things got ugly, if we were feeling homesick or started fighting. It would be us, our skills as team players, our skis and our shelter at the outer edges of our comfort zones, in a white immensity of snow.

The sensation was very peculiar when we put our feet on the ice cap for the first time. On the one hand we all felt very excited, on the other perplexed. What had we gotten ourselves into?

Back home when I told people that I was taking a month off from work to cross a remote glacier covered island, most people looked at me as if I was absolutely crazy. When I added that I’m a founder of a young startup, the reaction was that I must be completely mad. Yet that is what Lucas Servant (Ignition Program), Maxime Lainé (Weesurf), Valentin Drouillard (Wape), Antoine Noel (Japet) and I decided, in August 2017, to do. We all had our personal reasons for taking on this challenge, but one thing we all shared was the desire to prove something to ourselves. The chance to really push ourselves to see if we had both the physical and mental resilience and the ability to remain team players even in the toughest moments, was our main collective motivation.

When putting together the team I was looking for people with determination, team spirit and depth of soul, all while having a taste for effort and risk. But those people also had to be entrepreneurs, I wanted to learn from them and share visions of entrepreneurship. The fact that we didn’t know each other from the start, was of course a risk. A bit like including a new member to a family after knowing that person for only a couple of months, or like introducing a new player on your football team mid-season. But the intense preparations made us get to know each other pretty fast.

Some of us started doing Yoga

There were quite a few challenges – like the fact that none of us had been crosscountry skiing before, and now we were taking on this 580 km trip. We hired Bernard Muller, one of the world’s most experienced guides, who had already successfully crossed Greenland twice. He developed a training program to make sure that we would be ready for all kinds of situations we could encounter during the crossing – including alpine skiing and pulling sleds. We defined an endurance training program, including crossfit, running and a lot of walking and some of us also started doing yoga. Since we were going to sleep in tiny tents and spend much of the time in somewhat uncomfortable positions, adding flexibility was a huge advantage. We also spent quite a lot of time on mental preparation, like reading books about great explorers like Mike Horn and Roald Amundsen. For me the most important book was “The First Crossing of Greenland”

by Fridtjof Nansen, a brilliant read for anyone, whether you plan on going on an expedition or not. And just like Nansen we then met the cold.

We knew that temperatures in Greenland could vary between –10°C and –40°C, and that the weather is highly unpredictable, anything from calm sunny days to violent winds or snow storms. I guess we all had the mental image of the North beyond the wall like in the series Game of Thrones in mind. In reality, the cold is constantly present. As I’m writing four months after the expedition, I still can’t feel parts of my feet. Out there the cold is a constant threat, no mistake is forgiven. When we woke up, the inner walls of our tents were full of ice, because of the condensation from our breathing. Each time we took a break our bodies cooled down very quickly. The first days were physically difficult, but without any particular problems – except that our feet hurt from not being used to walking so long in the cold. The landscape dazzled us, white ice as far as the eye could see, without any sign of life. Very soon one of the biggest challenges hit all of us – to think alone.

When you normally spend about two hours a week thinking about yourself, what do you do if you have eight to twelve hours a day of solitary skiing? The first hours we focused on warming up, optimizing our efforts, the last were more complicated. We then dissected our thoughts, our projects, our lives. It became an introspective and meditative experience that changed us all. As the days went by, we realized that everything was physical. There was not a single minute from sunrise to sunset where we did nothing. We had to take care of the burner, melt snow, eat, dismantle and assemble the camp, walk, heal, repair equipment, reorganize and take care of each other. The only time when our bodies were fully relaxed was when we finally lay on our mattresses, in our sleeping bags, wrapped in all their layers, like in cocoons. This became an incredible moment, calm and serene, but it only lasted for a minute, before we fell asleep.

Switching buddies

One of our most successful days also became one of the hardest. After walking for many hours, the wind was starting to rise. In our monotonous days, this strong wind brought us change and started to galvanize us. But the wind had already exceeded our decided limit by 10 km/h. We could not agree on whether to go ahead or put the tents up. There was a great risk that we would not be able to get the tents up and therefore freeze to death. This had happened to an expedition three years earlier. After a discussion, where everyone had to scream to be heard, we ended up pitching the tent. For sharing experiences, we decided to swap tent buddies every six days. This is a bit of a breach of expedition code, but for us this principle was an important part of the human adventure. And how we were able to discuss entrepreneurship and learn from each other.

Anyone who has worked in a startup knows that it is a fragile ecosystem, particularly at the beginning. The average age of our five startups was two years, that is just at the very beginning of a hopefully long and successful life. In Solen, the company I co-founded, we were four people when I decided to go on the expedition, and 12 when I actually left. At times I felt like the most selfish person in the world – I would abandon my co-founder and the team at a period when we needed all hands on deck. In addition, Solen was selected to be part of the Accélérateur program at Leboncoin in March 2018. So needless to say, I sometimes doubted my decision to leave. But at the same time I was always confident that this expedition would make me a better person and entrepreneur.

The sky and the ground blended together

Although very different, startups and expeditions do have many things in common, three things stand out:

- The vision. A startup needs a clear vision just as we had only one goal: to cross Greenland. Sometimes, when we moved forward in a storm, we could no longer distinguish the sky from the ground, it was mentally very challenging. But the vision gave us direction.

- At Solen we are always listening to market feedback and our clients’ needs. Understanding the surroundings helps us to make quick decisions. During the expedition we were constantly listening to temperature updates, wind speed and snow quality as these insights helped us decide how to dress and what distance to plan for the next day.

- Most important: trust. For more than a year my co-founders, Clément and Enzo and I had got to know each other, all our strong sides and weaknesses. I would not change them for anyone. Everything moves so fast in the startup world, that if you can’t trust your team, you’re doomed to fail. In the same way trust is crucial on an expedition if one person cracks, the whole expedition fails.

The best time of the day, the moment everyone was waiting for, was when we set up camp. We put up each tent one by one – all together. We felt relieved, leaving the kilometers traveled behind us. Then came the most enjoyable moment – when we took our shoes off, enjoyed cheese, sausages and Swedish bread with butter. Eating my pack of butter became a ritual, a moment of luxury. We forgot all that was outside, our hardships and the cold. The physical effort also made us forget our daily lives in France. Strangely we realized that we didn’t miss anything except our loved ones. We did nothing but eat, sleep, talk, walk and think. We started to see things differently, everything seemed simpler and clearer. We finally saw ourselves as we were, not playing roles or trying to be someone else. The trust and respect between us were fundamental.

Back in France I realized that I have never experienced anything like this. It was our first adventure, and we’re already waiting for the next. Before going on this expedition I always thought that big adventures weren’t for me. Too hard, too far away, too expensive, too time consuming. But despite all that, I went on challenging my limits with five guys I didn’t know. Everyone can wake up their inner adventurer as long as you’re committed and humble in the face of nature.

The future of retail

The future of retail

This year Future Report and Inizio investigate digital shopping habits among millennials in Sweden, France and Spain. Turns out webrooming has been a bit overestimated.

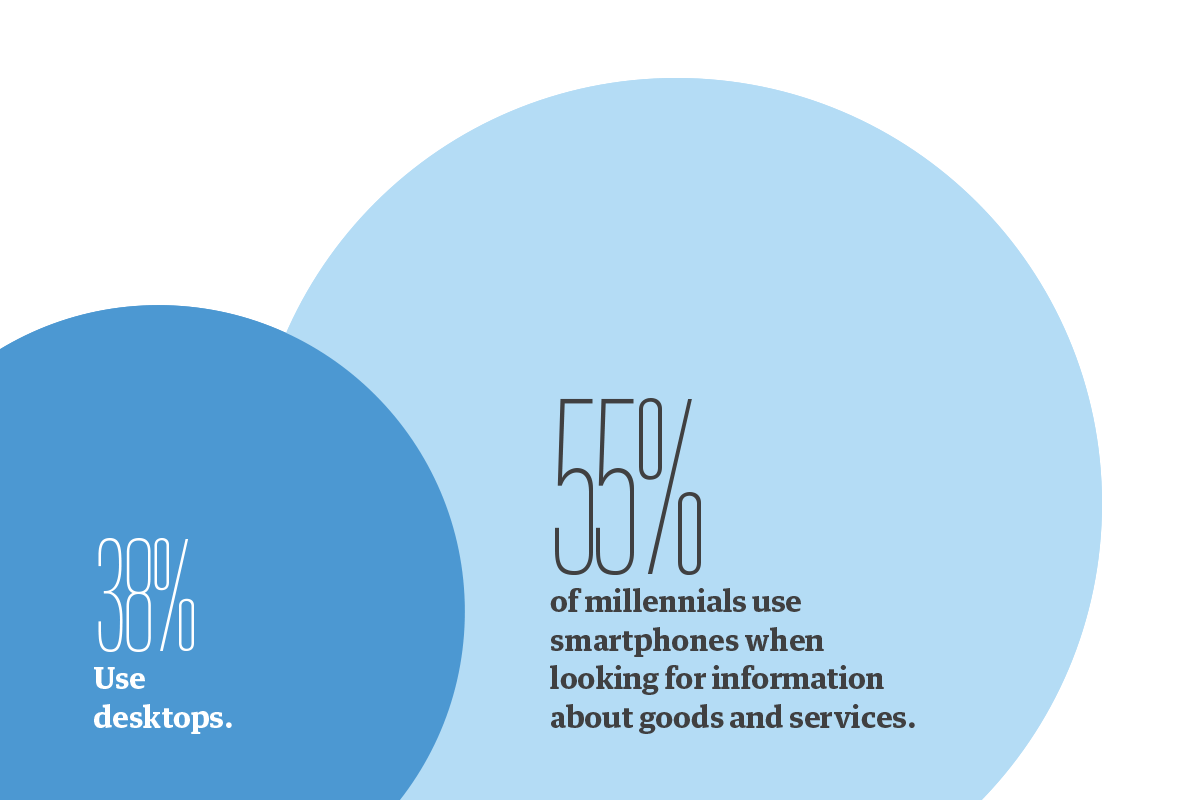

Traditional retail is going through rapid change. Online, offline, logistics and data are about to be integrated, fueled by tech like location data and augmented reality (AR). Jack Ma, former CEO of Alibaba, coined the term “New Retail” to describe this future of commerce. In this year’s edition of Future Report we explore the field in a survey among millennials in Sweden, Spain and France. We find that the mobile phone is the obvious way of shopping. About half prefer the mobile when they search for information about a service or a product.

55 percent of millennials in France, Sweden and Spain prefer to use smartphones when looking for information about goods and services.

Voice is a technology well-placed to develop. A quarter of millennials in Spain use it but only a few in Sweden. Sweden is lagging behind when it comes to launching devices, probably because the language is small. Many say they plan to buy a device, so the user base will grow. There is a considerable user base on mobiles too, another path to unlock voice commerce. Overall, how fast this field will develop should depend on how companies like Amazon and Alibaba, having their Echo and Genie hardware to draw upon, will choose to focus their business. Social commerce describes different online collaborative shopping tools in social media such as user ratings, recommendations or sponsored content by friends or influencers. The potential has been widely discussed and it is most widely spread in Spain, where 71 percent have bought something based on this, compared to 58 percent in France and 47 percent in Sweden.

Webrooming and showrooming have been debated a lot. Showrooming can be defined as a shopper visiting a store to check out a product but then purchasing the product online. Webrooming is when a shopper researches products online but buys it in a store. Our survey shows that webrooming seems to be a stronger trend, even though a lot of shopping is happening exclusively online among millennials. We are still surprised to see that shopping in stores is still going strong, not only for consumable products. Not every retail category is as likely to see a jump in changing behavior.

Here’s more insights from the survey: Insight story – full report

Trends in Brief

Trends in Brief

With new tech like augmented reality, virtual reality and voice, the big question is always; how do we monetize this? For visual search, it’s another story.

Visual search can boost your sales

With new tech like augmented reality, virtual reality and voice, the big question is always; how do we monetize this? For visual search, it’s another story. Before the tech even became a big phenomenon, e-commerce companies were already finding multiple ways to boost sales with it. Earlier this year, Amazon and Snapchat announced a partnership where users could take a photo of an item they liked in Snapchat and find it on Amazon right away. Ebay has similar tech and of course, Google is adding it as well. The latter has been using visual search for years to help people find similar looking pictures. In the coming years, the focus will be on increasing the tech’s accuracy and finding even more ways to guide users to purchases.

“Retail has always been a theater”

The experience economy is growing. The term refers to businesses incorporating experiential components into their offerings. One example is the Museum of Ice Cream in San Fransico. At the fake museum/pop-up store, visitors can pose in Instagram-friendly ice cream-themed installations after paying up to 38 USD per ticket. Critics call it a brain-dead funhouse, but the concept store is doing well. Over 1 million people have visited it so far. The Museum of Ice Cream has built a strong brand and is capitalizing on it through a nationwide merchandise partnership with Target. “Retail has always been a form of theater, of staging and storytelling, with products as cast members”, Target’s chief creative officer tells Bloomberg.

The (not so) sharing economy

Last year, the sharing economy was praised as the solution to all our sustainability anxiety. Well, that might not be true. Even though the ideas and visions are nice, the sharing economy is up against some pretty big roadblocks.First off, investors are more eager than consumers. Rewiring people to prefer sharing over owning will take some time. Secondly, the people who actually use the sharing services are not handling it that well. Consumers don’t return what they borrowed, treat it poorly, and ignore direction for usage. In San Francisco, electronic scooters you rent with an app became an over-night success. However, people immediately started putting them anywhere when they were done, creating a mayhem for other commuters, and soon they were banned.

Ellen Montén

World wide Amazon

World wide Amazon

By constantly playing the long game, Amazon stands to disrupt any business it enters. The question is what costs and consequences will come with it?

When asked what Amazon is, most people will likely answer that Amazon.com is an e-commerce destination. Some may point out that they also offer cloud services for developers. Others may note that they build consumer hardware such as Kindles and Echos. Fewer may say that Amazon is also a distribution player that builds advanced robotics systems for its own fulfillment centers and buys airplanes for fast overnight deliveries. With the purchase of Whole Foods, Amazon now owns a supermarket chain and is also an advertising player. In fact, it’s more or less impossible to describe it in a simple way, but one thing is for certain; Amazon is set to scale across the planet like no other company before – all in the name of the happy customer.

At its core Amazon is a company that leverages economies of scale and it does it perhaps better than ever done before. Economies of scale are achieved when an investment in operations can be leveraged to decrease the cost per unit of output with increasing scale. A classic example is the printed newspaper. Somewhat simplified – the cost of the very first newspaper printed in a printing plant is equal to the cost of the plant, while the cost of the billionth newspaper printed is equal to one billionth of the cost of the plant.

The bookstore scaled up

With the introduction of software, economies of scale became almost limitless; Microsoft developed Windows and then licensed it to computer manufacturers, Google indexed web sites that were built by the rest of the world to be searched and Facebook built the social infrastructure and let the users create the content to be consumed. What is unique about Amazon is that it excels at scaling in both the physical and the digital world. The origin story of Amazon is well known. It started as an online bookstore. The founder Jeff Bezos’ analysis was clear – retail will shift online, physical bookstores can only offer a limited selection of all books ever published, books are easy to ship and sourcing of single copies of books for delivery is simple. Building the online bookstore represented a significant initial investment, but thanks to economies of scale the cost per book shipped would decrease with every new book shipped.

Five percent of all US retail

Once at scale it was not a big investment to begin selling other categories of goods. As the store grew Amazon invested in fulfillment centers, large warehouses to store and package goods to be distributed. Goods need to be sent to and from these centers and Amazon is investing in its own distribution network of trucks and airplanes to reduce the costs of transportation. The fulfillment centers and the distribution network represent large investments, but by making it all available to third party retailers through Amazon’s online store they achieve scale faster.

Amazon has so far made most of its investments in their home market and now about 50 percent of all e-commerce in the US is happening through Amazon. Still, this only represents five percent of all US retail sales so there is still room for a great deal of growth as more and more retail shifts online. At the same time, Amazon is making significant investments in building fulfillment centers around the world. In fact, more than half of its current 750 distribution facilities are outside of the US, including 194 in Europe.

The online store operates on servers that run software. Both the store and the servers represent significant investments, but by making software available for others to use they again achieve scale benefits. This particular business is called Amazon Web Services (AWS) and has become highly profitable, representing about half of Amazon’s recent profit, with a margin above 25 percent. This is truly an indication of the potential of all of Amazon’s long term investments. In fact, having a long term outlook is a unique characteristic of Amazon. This, and relentless focus on the customer has allowed Amazon to grow its sales exponentially while reinvesting almost all of its net profits into scaling its businesses.

Even with almost no profit, the market has rewarded Amazon with a valuation of almost one trillion US dollars. This is because the market understands what Amazon is doing. Continued investments into scalable operations create a moat that potentially no other single company will be able to match. Alibaba and Flipkart with their respective dominance in China and India are in a position to achieve something similar, but otherwise only massive consolidation of retailers, e-commerce and distribution players can offer serious competition against Amazon. All of the investments aim to build horizontal businesses that benefit from network effects; in e-commerce, more buyers lead to more suppliers lead to more buyers. In cloud services, more tenants lead to great economies of scale, in terms of servers as well as software development.

“Continued investments create a moat that potentially no other single company is able to match.”

At the same time, Amazon is investing in vertical integrations. During the past two years the company has introduced more than 80 private labels to sell their own versions of products including clothing, shoes, jewelry, garden/outdoor, grocery, health/household and home/kitchen. And with Amazon Prime, a subscription bundle, built around the promise of always free two day delivery of most goods, customers loyalty is secured. The bundle now includes Prime video as well as an assortment of other digital services and its own brand for everyday commodity essentials, AmazonBasics, is only available to Prime members. At the beginning of 2018, Amazon had more than 100 million households globally signed up to the 119 USD per year service.

Alexa directs consumers

When a household signs up for Amazon Prime they generally make all future online purchases through Amazon. Once within the ecosystem, they are more likely to purchase an Echo compatible device (about 50 million shipped so far) that allows them to make purchases by directly talking to Amazon’s Alexa who will generally recommend Amazon’s own products or those labeled as Amazon’s Choice. Amazon is clearly moving the customer towards reducing the number of choices they make, especially choices that lead them away from the company. They now also sell door locks that can be remotely opened by their couriers letting them make deliveries directly inside the household. The next logical step in home automation is restocking of the refrigerator. Once deployed households can have their refrigerators replenished automatically by couriers that enter and exit the home while the members are at work and school. A kitchen full of goods without a single decision being made.

If more and more purchasing decisions are made by Alexa instead of the customer the advertising business will change fundamentally. And if the majority of the purchasing decisions are made on Amazon and you get 100 percent confirmation on how well your advertising performs as the purchases are also made on Amazon, why advertise anywhere else? Amazon’s advertising business is booming, in Q2 2018 it generated $2.19 billion, up 132 percent year over year.

Taking the long term perspective on this tremendous growth founded on the ambition of being the world’s most customer centric company, one can wonder where it all ends? A question that gets even more important when considering that Amazon, together with Facebook and Google, excels at not paying taxes. No doubt the company builds its value on top of the collective global infrastructure which to a vast extent is financed and made possible by governments across the planet, yet avoids sharing in any of the costs. Marketing guru and tough critic of the same companies Scott Galloway wrote in late 2017: “The most disturbing stat in business? Since 2008 Walmart has paid $64B in corporate income tax, while Amazon has paid $1.4B. This is despite the fact that, in the last 24 months, Amazon has added the value of Walmart to its market cap. The most uncomfortable question in business, in my view, is how do we pay our soldiers, firefighters, and teachers if a firm can ascend to $460B in value (#5 in the world) without paying any meaningful corporate taxes.”

An exponential scale

By consistently playing the long game, Amazon stands to disrupt any industry it enters while making more and more businesses dependent on its own infrastructure. Currently, less than 1 percent of global retail is happening through Amazon, so the growth potential is almost limitless. But what happens when that one percent becomes ten and beyond as the juggernaut continues to scale exponentially? A great deal of responsibility now lies on the shoulders of regulators in the EU and the US who quickly need to understand if and how to regulate a company whose genuine primary objective is to meet the demands of the customer – at any cost. This will challenge the current interpretations of anticompetitive laws. Some legal scholars, such as Lina Khan, suggest that the US needs to again strengthen its once robust monopoly laws in order to break up Amazon. The one trillion dollar question that now needs to be answered is: what costs and consequences are we as societies willing to accept as Amazon disrupts its way across our planet all in the name of the happy customer?

Don’t worry – it’s getting better

Don’t worry – it’s getting better

Looking at pure facts, the truth is that the world is getting better in many ways. But this is news that seems hard to establish. Anna Rosling Rönnlund and her partners in Gapminder are devoted to spreading a more complete picture of the state of things. “It’s not that we are driven by being optimists. We’re presenting facts that scientists agree on. And we’re frustrated that people believe that things are worse than they are”, Anna Rosling explains.

Gapminder is a foundation, known to many through Hans Rosling, Anna’s father-in-law, who passed away 2017. Hans traveled the world to present unique visualizations of facts on global economy, health and demographics. He had many fans, including some of the world’s most famous people – like Al Gore, Larry Page, Bill Gates and Barack Obama. Anna and her husband Ola Rosling founded Gapminder together with Hans and are now continuing the mission: to work towards a fact-based worldview that everyone can understand.

How many of you would have guessed that 90 percent of all girls in the world are going to school or that the share of people living in extreme poverty has halved over the last 20 years? Not many, probably. Gapminder has tested a lot of people, and a great majority have misconceptions of the world. That also goes for professors and experts. Anna believes that fragmentation is one reason.

“Some blame media, but their job is to report on things that are not normal. We think that schools are the ones that need to fill in the gaps.” At one point Gapminder was invited to Google to work on making the data accessible. “But we realized that it was still hard for people to find it and to put it into a context. That’s when we knew we needed to work with schools”, Anna says. So Gapminder has hired two teachers to better understand teaching needs. And their new book Factfulness was written with a highschool teacher in mind. They have also made tutorial material for the book.

“In the long run we need to find better ways of teaching social science in school.” In the end Anna is in fact an optimist – at least when it comes to data and information. “We have access to more data than ever. We just don’t know how to process it yet.”

At war in social media

At war in social media

Social media has become the arena for an information war, where private companies offer fake net identities to use for influencing. This is how the world of bots and propaganda works, writes Karin Pettersson and Martin Gelin in their book “Internet är trasigt” (The Internet is Broken).

Alabama is in the Deep South of the United States, where racism is at its liveliest. It was here that Donald Trump held an open meeting in the fall of 2017 and chose to vent his spite on the black American football players who, instead of honoring the flag during the national anthem, knelt in protest against racism. “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ’Get that son of a bitch off the field right now’”. Trump’s words were clearly intended for his core voters in Alabama. His comments exploded in social media and later also in the traditional media. The topic was ideal for Trump, who feeds on war on cultures, polarization and wrath.

But it was also perfect for the Russian president Vladimir Putin. That could be noticed in real time on the surveillance site Hamilton 68, which is tracking more than 600 Russian propaganda accounts. The Russian propaganda apparatus loved the story and did everything it could to enhance it. The accounts were tweeting like mad, making up new hashtags and spreading every possible bit of the story.

They most likely contributed to the topic attracting so much attention and growing so big in the public domain for such a long time. The Kremlin is very astute at propaganda, as it were. And the structures that Adrian Chen and Jesikka Aro identified in 2014 have only grown more powerful and efficient since then. Around the world, countries are building social media armies in order to protect their own populations from foreign influence or efforts to influence them in a certain direction – alternatively, as in the case of Russia, to control the debate at home and abroad.

“Around the world, countries are building social media armies.”

There is an example of cyber defense in Estonia where they, after having been subjected to heavy IT attacks in the spring of 2007, formed something that resembles a digital home guard: “Estonian Cyber Defense League”. Ordinary people who, in collaboration with the armed forces, counteract Russian propaganda. In a report about Russian influencing operations in the Baltic states, Stratcom (Nato’s strategic communications center) showed that 85 percent of all tweets in Russian about Nato came from bots.

One of the reports produced by Oxford Internet describes the possibly hardest thing to get at, but is becoming more frequent. It has to do with private companies producing fake net identities which then can be used to influence what impact a company or political idea has on the net. An example from Poland reveals how a marketing and communication firm over several years created 40,000 false identities, all of them with real names, IP addresses and personalities. Each one of these “persons” then has several accounts in different social media, offering the possibility of making a heavy impact for someone who can afford it.

15 fake accounts at a time

The theory behind this business is called “false amplification”, to give material and opinion a distribution that they would otherwise not have. The way it works is that real persons manage false accounts, as many as 15 accounts at a time. The trick is to be very careful to use real photos and make the accounts look “real” so that they are not detected by the filters at the social media companies that try to weed out fake identities. Then these fake accounts are used to write in comments boxes, Facebook groups or on Twitter. They use VPNs or false IP addresses and because they are so cleverly masked they become practically impossible to detect, both for the social media companies and for the world around us. This in turn creates safety and distance for the buyer of the service. The strategy applied by the companies is not to inundate social media with their message and get hashtags trending, but much subtler. It is about influencing opinion leaders, including journalists, politicians and activists. This is done by infiltrating important Facebook groups, writing comments and interacting directly with people who are important to reach. The aim is to influence these people, making them believe that the false identities truly believe in what they argue for.

Still many people, including journalists, believe that what you see on social media expresses the will of the people or mirrors the population, but without carrying out qualitative research it is very hard to draw any conclusions as to what it means when certain topics are trending or not on social media.

n the fall of 2017 Facebook, Twitter and Google were summoned to the US Congress to testify on how their platforms had been used by Russia in order to influence the election. The testimony from Facebook showed, among other things, Russian advertisements. In Pennsylvania, one of the states where the result of the election was unclear, the Facebook account “Being Patriotic” posted ads for a demonstration that was going to gather “miners for Trump”. The ad was aimed at male voters. “Donald Trump has said that he is going to give miners their jobs back” was the message. He had not said that, but that didn’t bother Moscow. Actually, it emerged, after an internal investigation at Facebook, that the ads were a part of a propaganda push controlled and paid for by Russia. Trump won Pennsylvania with a margin of less than 45,000 votes.

A frightening naivety

The weaknesses of the internet have been used by countries for several years. In many places, however, there is a frightening naivety in this field. This also goes for journalists who still are too uncritical when referring to the content of social media – regardless of the fact that the far right has organized Twitter storms for years, with the aim of influencing the media and the public opinion. Simply put, social media is not a place where the interests and views of people are reflected in a neutral manner. It is an arena for organizing, chatter, entertainment and information war. It is also a world where those with the loudest, most polarizing and most controversial opinions make the heaviest impact. In many (Swedish) newsrooms the awareness of influencing campaigns and the need for fact-checking and verification has increased. But in other places there is still a great naivety concerning the propaganda war of the new age, and what role the media outlets themselves risk playing if they don’t understand the new rules of the game.

Disrupting the information ecosystem

Disrupting the information ecosystem

We’re living in a new reality, where economic inequalities, climate change, migration flows and technological disruptions are shaping the world. It’s also a time of strong men and of the rise of authoritarianism. We tend to talk and worry a lot about Donald Trump, but it’s not only him. There’s Erdogan in Turkey, Orban in Hungary, Duterte in the Philippines, and Putin in Russia. And many others.

And there’s a fundamental question I’ve been asking myself the last years: Where does all this rage come from? In my former job as Political Editor-in-Chief at Aftonbladet I could feel the rising anger in a very concrete way, in my inbox and my social media feeds. Year by year, the level of hate and threats and aggression grew. I am an economist by education, and my instinct is to look for answers in the economy; disrupted labor markets, globalization, people being left behind. All of these factors are important. But as I traveled a lot in Eastern Europe last year, in Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, the story still just didn’t add up. These are countries with high growth and low unemployment. Despite that, the rage, the explosive media and political climate was the same as in the US, the Philippines, Turkey and yes, in Sweden.

Something has gone wrong

The level and intensity of rage just does not seem proportionate to the underlying, observable changes in economy and culture, as historian Anne Applebaum put it when I interviewed her in Poland last fall. The X factor seems to be how today’s internet and social media are shaping our public discourse. I used to be a fan of Mark Zuckerberg. Or at least of the tools he built. But something has gone wrong.

The problem at the core of this is that the content that’s most misleading or conspiratorial is what’s generating the most engagement, and that’s what the algorithm is designed to respond to. The stronger you react to the content you see on Facebook or YouTube, the more likely you are to remain on the platform. And the longer you stay, the more money they make from your data. In this way, the tech giants’ business models create the economic incentives now driving outrage, disinformation and polarization.

Tech giants distort competition

In today’s world, the logic of the attention economy overlaps with political forces with the stated aim of undermining liberal democracy. This is disrupting the ecosystem for information and challenging the ethos of journalism. But there is more to this story. The tech giants are also disrupting our economic structures. We see them growing data monopolies, using that advantage to distort competition. Google is pushing its own products with the power of its massive search engine. And Facebook is rolling out its own marketplace that the users cannot avoid. Their dominance is hurting jobs, innovation and our basic ideas of fairness and competition.

Change and pressure need to rise on many levels. From consumers, citizens and politicians. We need to understand how economics plays into this, the logic of the attention economy and the business models. Because at this point the sheer size and power of these companies are a threat to how we organize our societies. The good news is that the time is right and we see reactions.

Like from Margrete Vestager, the Danish EU competition commissioner. Or, as the Financial Times calls her, the “slayer of big tech”. Vestager has ruled that Apple needs to pay more taxes and has twice heavily fined Google for illegal behavior. GDPR and privacy is part of the backlash, as is the copyright vote in the EU. The world is slowly waking up and starting to realize what values are at stake.

Schibsted has a role to play

In the end this is about standing up for what we believe is important, and the truth is that companies like Schibsted can play a role in all of this. Schibsted has been careful in the past not to go all in on the platforms. We have kept the relationship with our readers and users in our own hands, to a large degree. We are small compared to the giants, but we are not owned by them – and we have a history with legacy. We are in the middle of this perfect storm in these pretty dramatic times and it’s a challenge, but honestly it’s also exciting and interesting.

Promoting diversity from the inside

Promoting diversity from the inside

In 2017 the #metoo campaign propelled gender equality and diversity conversations to the forefront of organizational debates worldwide. Since then the various benefits of creating a diverse and inclusive workspace have been widely discussed.

Schibsted, with its international Marketplace portfolio, has always had a naturally diverse culture. But as a company, we want to do even more. That is why diversity and inclusion became a topic of high priority in 2018. From the beginning it was clear that creating a cultural shift wouldn’t be easy, and that in order to achieve it we would need to invite advocates and influencers across the globe.

In October 2018 Change-Makers was born. 16 individuals across eleven countries came together to share, shape and build a movement of change. Change-Makers is not a traditional diversity and inclusion program. It’s a community that believes in creating change from the inside in order to transform our workplaces into spaces where differences are embraced, and everyone feels empowered to realize their full potential. The vision for driving change is twofold. On the one hand, we aim to encourage our community to empower each other. We do this through different tactics such as soft skills development, workshops on diversity, career planning, etc. At its core, Change-Makers is about identifying and solving root cause problems.

On the other hand it’s about organizational change. We believe that this new community will be a key pillar in creating workplaces that are bold enough to tackle real problems such as maternity and paternity leave policies, attracting (and retaining) more women in tech and embracing the benefits of having diverse teams. No one ever said change was simple, but having an organization that supports its individuals and communities is the first step towards creating a future we can all be proud of.

Elianne Mureddu

Caroline von der Mosel

Trends in Brief

Trends in Brief

“Why is it not working?” seems to be one of the most asked questions in every meeting room. Many companies claim that they will deliver a “one-click” solution, but some are thinking even further. Earlier this year, Microsoft showed off a 360 degree camera and microphone, specifically designed for meetings.

Meeting rooms of the future

“Why is it not working?” seems to be one of the most asked questions in every meeting room. Many companies claim that they will deliver a “one-click” solution, but some are thinking even further. Earlier this year, Microsoft showed off a 360 degree camera and microphone, specifically designed for meetings. The camera can detect anyone in the room and throughout the meeting, and the microphone transcribes everything they say, regardless of language. Microsoft has also added AI that listens in on the meeting and reacts to certain words and phrases, sending out notifications to participants who, for example, promised to book a meeting. Amazon’s Alexa has a similar setup, and can also check that all the tech is working beforehand.

The legalities of the gig economy

With companies like Uber, TaskRabbit and Postmates, the gig economy got a new face. Workers are encouraged to join the services and work whenever they want, wherever they want, which might sound good to many. However, in reality, the “no full-time contracts” business model has been criticized for hurting workers’ rights. When Uber pays way less for their drivers, it makes it impossible for competitors to keep up without lowering their own drivers’ salaries or adopting the same business models. Supporters call it a revolution and point out how cheap a taxi ride has become with Uber, but the opposing side has already managed to have Uber’s original business model banned in a long line of cities, including London.

How to make your hires smarter

Removing names and pictures from CVs was just the first step. In an effort to remove biases in hiring, big tech companies have found new ways to filter out talent. The startup GapJumpers, which collaborates with Google, has created a software program that facilitates blind auditions solely focused on an applicant’s skills (like on The Voice). The company has found that this increases the number of female applicants and employees, which is something Google has had a big problem with before.

Another startup in this field is Textio, which helps companies write job descriptions with less gender-associated words. There are also job sites that think outside the box, like recruitment marketplace Search Party, which only shows employers anonymous profiles with just enough information to make an informed hiring decision.

Ellen Montén