Tech has always been the future

Tech has always been the future

I am still a technology optimist, but I have also become a technology realist, writes Sven Størmer Thaulow, Chief Data and Tecnology Officer in Schibsted. His interest in tech was awakened in his early years by his grandmother.

Most of us trace lines back to when we were children in order to better understand the people we have become. I have always been a tech optimist with an eye to how technology can improve our lives in the future. It all started when I was a kid in the 80s.

I first saw a computer in the computer room at the research institute where dad worked. It was a sharply lit room full of large machines with tape wheels moving back and forth. The room was full of noise, the air was dry, and a barely detectable breeze was in the air. There was much optimism about how these machines would be used to find answers to scientific problems which required large amounts of data to be solved, such as finding out how pollution spread in waterways. To an 8-year old boy, this was impressive – and not least thrilling.

Yet, when I think about what influenced me to become a tech optimist, the big machines are not the first thing that comes to mind – it is my grandmother. She lived in a flat in Oslo with grandad, who was a research scientist. Together they often traveled – especially to the US, where they had many friends in academia in Boston.

A lethal device

When grandma came home from the US she always brought new technology with her. I remember the electric bread knife with the two blades going back and forth – an innovative and lethal device (we were instructed to stay clear when Grandma was slicing bread). Then there was the electric jar opener, which – we were told – was developed in collaboration with Nasa. Totally awesome, but sadly not very useful. Yet Grandma was always incredibly optimistic about how technology would develop and what opportunities it would bring. Her unshakeable belief in new technology stayed with her until she died in her 90s.

Yet, technology optimists always meet sceptics. My mother was the sceptic in our family: video (VHS) did not belong under our roof – there was too much violence, with Bruce Lee and chainsaw massacres. No wonder then, that when grandma called from Boston in 1979 and wanted to get a personal computer – the next big thing – for “little Sven” this was flatly denied by my mother. But at least grandma managed to smuggle me in a Merlin, leading my interest in computers to blossom.

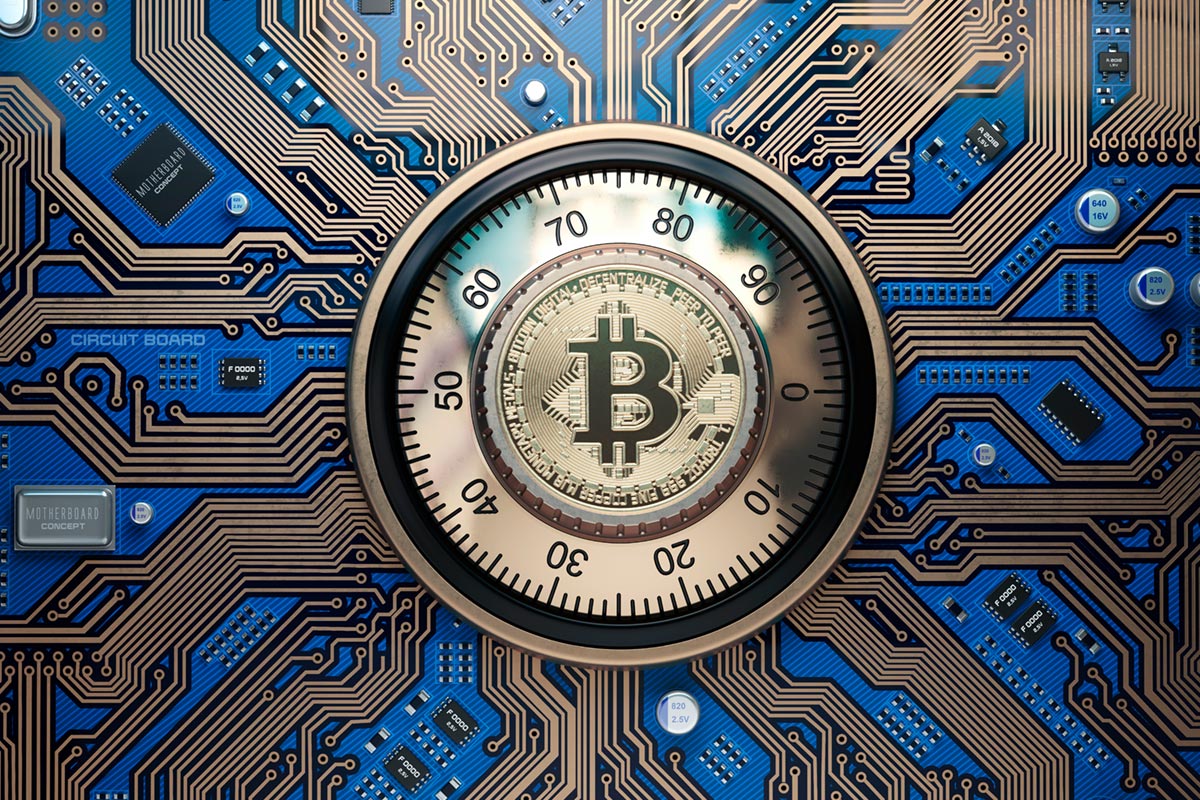

Now in 2019, technology optimism has been replaced by technology pessimism: crypto-currency – which was supposed to be a tool for good – has become a tool used by criminals to buy and sell drugs and stolen goods. Genes can be sequenced for USD 1,300, and we have genetic modification technologies we could only have dreamt of back when my grandmother wanted to get me that computer. Artificial intelligence – once considered a possible answer to many of humanity’s great challenges – is now seen by some as a threat.

Our responsibility to be wise

Technology develops constantly. Today, it is not just part of our surroundings – like an electric bread knife or two – but it permeates every aspect of our society and our daily lives. At the same time, legislation is lacking, unclear, or simply difficult for ordinary people to understand. In this landscape, more and more responsibility rests on us as individuals – both at work and at home. It is our responsibility to consider whether it is okay to give away our data or if we (as people who develop technology) want to use data for a certain purpose or not. Not least, it is our responsibility to be wise about using technology where we collect data about people: how do we explain to people in a clear and comprehensible way what their data is being used for? These are issues we must all think about, whether we work with technology or not. Let me give you some examples.

More and more homes are smart. You might not think about it, but if you have installed an alarm in your house that connects to a front door that uses a code and not a key, you are already facing lots of ethical issues. The lock on your door can record when people come and go. Should you use it to see when your spouse leaves or comes home? The technology is there – it is your choice.

You’re working at a genetic laboratory in a hospital. You know the patient whose DNA you are now scanning personally, and discover that there is a relatively high chance she will get an incurable disease in the future. Do you inform her? The technology is there – it is your choice.

You are working at a weapons factory and are developing semi-autonomous weapons. You discover that with facial recognition technology the system can find the targets on its own, and a soldier only has to press a trigger. Is this crossing the line? The technology is there – it is your choice.

You are working in Schibsted and realize that if you tweak the machine learning algorithm you can increase how much time the average user spends at Aftenposten and earn more money. You are concerned about “algorithmic bias” – that you can alter the algorithm to produce content that pushes you closer to an echo chamber. Should you use the algorithm? The technology is there – it is your choice.

Or perhaps you are like me, who has sent a sample to a big company to find out how much percent African, European or Neanderthal you are. Quite fun and not too pricey! But where did that data go? Maybe it can be used to determine your children’s insurance premium in future? The technology is there – it is your choice.

What is important to keep in mind is that the technology itself is not harmful. Whether or not it is harmful is determined by how we choose to use it. I am still a technology optimist, but I have also become a technology realist: everyone must use technology, whether we work in the technology industry or not – but we must be much more mindful of how we use it, and consider the ethical challenges we are faced with.

Technology scepticism is no way to go. I want to be like my grandmother who never ceased to be fascinated by technology. On one of her last days as a 97-year old she streamed National Public Radio and chatted to her old friend in Boston – on her laptop.

Sven Størmer Thaulow

Chief Data and Technology Officer

Years in Schibsted

0.5

My dream job as a child

Inventor

Crooks benefit from privacy protection

Crooks benefit from privacy protection

Last year Alex Stamos was one of Facebook’s top executives. Now he sits in a rather unimposing office at Stanford University outside San Francisco. Although Facebook’s headquarters in Palo Alto is only a short walk away, the distance between them is long.

“The platforms are delighted about not having to share.” Facebook’s former chief security officer warns against exaggerated privacy protection.

“It’s personal. I don’t talk much about that.”

According to The New York Times, Stamos left after a disagreement with the rest of the executive management over its handling of Russia’s attempts to spread fake news on Facebook. Stamos wanted openness, the others did not. Following a board meeting at which Stamos informed the board about how the platform was being misused, Sheryl Sandberg is reported to have yelled at him in front of witnesses: “You threw us under the bus!”

But that is not something he wants to talk about. He would rather talk about the Cyber Policy Center he leads at Stanford University and – ironically – how difficult it is to cooperate with Facebook and the other tech giants. Sitting in his modest office at Stanford, Stamos is trying to launch his new baby, The Internet Observatory. As the name suggests, the idea is to build a system that facilitates research online and find out what leads to radicalisation and extremism, child abuse, bullying, suicide, manipulation of democratic elections and all the other shit that’s going on out there.

Research needs data

The problem is that research needs access to data, and most of the data on what is going on in our common digital cosmos belongs to the tech giants Facebook, Amazon, Google and Apple. They are the world’s richest, thanks to the data they have collected and exploited to build goods and services the world wants.

Their servers are the tech industry’s equivalent of Fort Knox. Their data is their gold, and it would take a lot for them to allow others access to it.

“There’s barely an aspect of humanity that has not been changed by the internet, and not all those changes are for the better,” says Stamos.

“If you’re going to predict and counteract the harmful aspects, you can’t just base your research on opinion polls. Only authentic data can give a true picture of the problems and of how we can combat them,” he says.

The current conditions for researching the internet are difficult. Each research project needs people who are familiar with different programming languages, others who can resolve legal tangles, and still others who can gain access to data belonging to the various parties.

“Just as a space researcher can gain access to an observatory, so we are trying to create an infrastructure for research online once and for all.”

“I hear you’re having problems getting access to data from the big platforms,” I say. Samos shrugs his shoulders.

“Not just us; this is a problem for the whole of academia.”

Ok, I think to myself. But after all the scandals surrounding Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, most people are probably unsure of whether it is a good idea for the platforms to share their data with others.

The pendulum has swung too far. It’s perfectly possible to share large datasets without sharing personal data.

“The pendulum has swung too far. The Cambridge Analytica scandal and GDPR (the General Data Protection Regulation recently introduced in the EU) has created the illusion that all data transmitted by enterprises constitutes a scandal. It’s not. It’s perfectly possible to share large datasets without sharing personal data. Privacy protection must be balanced against security and competition. Today, crooks and perpetrators are also benefiting from extreme privacy protection, and research is suffering from it,” says Stamos.

But to my mind the problem doesn’t stop there. Even if laws and regulations made it easier for companies to share their data, I doubt they would do it. If I pick a full basket of lovely mushrooms, there’s nothing to stop me from sharing them with others. But I have no incentive to do that. I would rather fry them in butter and eat them than give them away to research. Stamos laughs.

”A fascinating potential”

“The platforms are delighted about not having to share. It means that any mistakes they make will often not be detected, and that they avoid competition,” he says, as he assumed a more serious expression.

“But they may be required to share. They’re too big and powerful to not be researched. When SSIC (United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence) investigated Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election, this was mentioned in the final report.”

I’m sitting across the table from him and wondering whether nation states have something to learn from the platforms’ data strategy. What if Norway, for example, were a start-up company and Stamos the entrepreneur? How would he have created value from the country’s vast, buried treasure chest of public data?

“I would have gathered accessible datasets in one place, washed them and got them to talk to each other. Then I would have classified them according to how sensitive they were so that I could build a platform that allowed access to the data on different levels. As a country, I might have left the practical aspects to a company that was subject to stringent regulation, as in the oil industry. You can’t just take a huge drill and drill a hole in the bottom of the North Sea. A rig like that could facilitate research and make it possible to create new value and jobs that benefited the common good.”

“Who should invest then?” I ask.

“The state. A country that invests in this could lead the way in realising the value of public data without violating the rights of individuals. A fascinating opportunity with huge potential,” says Stamos.

Joacim Lund

Technology commentator, Aftenposten

Years in Schibsted

14

My dream job as a child

Musician

Public data is a hidden treasure

Public data is a hidden treasure

Amy Webb is one of the world’s foremost technology experts. She thinks that the Nordic countries are sitting on treasure chests of public data. The question is who should carry the costs and the work of digging them up – and take responsibility for the content once it is up.

“A revolting, rat-infested cesspool. No human being wants to live there”.

Donald Trump cannot possibly have meant Amy Webb’s neighborhood when he once fired a broadside at Washington DC’s neighboring city Baltimore. Based in a luxurious house overlooking the city she is writing books on technology, manages the Future Today Institute which is publishing a yearly report about technology trends and is preparing her lectures at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

The last time I saw Amy Webb was in March. She was on stage at the large tech conference South by Southwest in Texas That has become a yearly fixture. Everybody is trying to look into the future. She is one of the most ardent observers.

“The clearest trend this year: Privacy is dead”, she said.

Data can be use to solve the problems of the world

“It looks as if I was right”, she says simply from the sofa.

“Every time we use one of our gadgets, we produce heaps of data. The tech industry is gathering and using these data. It probably feels safe when you draw your blind and go to bed, but in principle we are being watched all the time. That is not necessarily something bad, but we have to be aware of it and think of what consequences it might have”, she says.

That is precisely what I want to talk about with her. The value of data. Not the fact that Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple have become the richest in the world by developing service that people want in exchange for knowing everything about them. That’s common knowledge. It is also well known that these companies do not always take good care of these data.

What is lesser well known, or at least is given less attention, is whether data can create value apart from making a few people filthy rich. How data can be used to solve the mystery of cancer, stop radicalization, combat global warming or produce more food for a growing world population. Data can be used to solve the problems of the world.

If they are accessible.

Amy Webb is leaning forward. Her leather jacket is creaking. This is where the battle of values is raging.

Transparency is the solution

“We are having a heated election campaign here in the US. Recently one of the presidential candidates pledged to fight for the right of every individual to own his or her data. That was met by a lot of eye-rolling in Silicon Valley. Someone even argued that people shouldn’t have any access at all to their data because they would not understand what they see. That is an extremely negative view of humans. But perhaps it is too simplistic to talk of private ownership of data in the same way one may talk about owning a cushion. It is more rewarding to fight for transparency. It is clearly feasible to let people have a say in deciding who should have access to their personal data and what they are being used for. The tech companies will roll their eyes some more and claim that it is not possible, but it is” she says.

But perhaps it is too simplistic to talk of private ownership of data in the same way one may talk about owning a cushion.

Maybe such a democratization would lead to more data being accessible to those who are working with research and development. For them, free access to the enormous amount of data stored by the big tech companies, would be a big, big step forward. But fortunately, these companies are not the only ones with capacity to collect and manage data. They have just been quick at doing so.

Norway, for example, has a treasure chest filled with public data. Possibly the world’s best health data, with a large amount of information all the way down to the level of individual from cradle to grave over a very long period.

But, just like most treasure chests, most of these data are buried, most of them in various silos, in varying formats where they are inaccessible for researchers who could use them to prevent and cure or to entrepreneurs which could use them to build health services and -products and to create workplaces and values for that matter. The question is who should carry the costs and the work of digging up the chest – and take responsibility for the content once it is up. Who is to decide what is a cost-worthy use of data and therefore should be prepared? Who is to be given access? Which role should the public domain play?

“Norway can do it”, Amy Webb says.

“Or Finland, Sweden or Denmark. The Nordic countries are extremely advanced compared to most other countries in the world. If there were to be a pilot project with openness transparency and participation in a good way, I believe it must be carried out in one of the Nordic countries.

Isn’t there a certain risk with that?

“Yes.I am giving advice to some big companies and what I see is that everybody is very excited by the possibilities to collect data about their users. But worryingly often they forget to put the important questions; what is it that we are actually collecting? How are we going to make use of it? Who is going to have access? When? What if it becomes difficult to keep it inside the country?

All this is already very complex and soon everybody must relate to both biometric data and behavior data to boot. The world needs more data engineers and the data engineers we have are working with safety and ethics and not just costumers’ satisfaction barometers” she declares preparing for landing:

“Risk does not mean that you must not do it. As a rule, the willingness to handle risk is what leads to profit, in the end”.

These are some of the main trends in the latest report from Future Today Institute: Tech trends in short

Joacim Lund

Technology commentator, Aftenposten

Years in Schibsted

14

My dream job as a child

Musician

When tech changes our view of the world

When tech changes our view of the world

What happens when augmented reality collides with the internet of everything? Some cyber prophets envision an enhanced mode of existence called the mirrorworld. But is the mirror already broken?

Looking back at the future can provide an interesting, if somewhat embarrassing, perspective on the history of innovation. Every new year brings new buzzwords, sounds of revolutions and paradigm shifts. But the truth is our ability to predict the future was never very astute.

One year the prophets assure us that the smart home is sure to change our lives, then 3D printers are on the verge of making factories obsolete, next comes the internet of things, virtual reality, augmented reality, blockchain, self-driving cars, artificial intelligence… Yet somehow these predictions repeatedly miss their mark. Another year goes by and neither society nor our lives are as thoroughly transformed as we envisioned. Instead other, uncharted tracks toward the future open up. Suddenly there are kids running around chasing pokémon all over town, sharing the streets with adults zooming recklessly through traffic on rented electric scooters.

To be fair, many of the innovations that were promised have, technically speaking, come to fruition. Augmented reality, for instance, has been available and widespread for many years. A few years ago, I visited the Googleplex in Mountainview and tried the (at the time) bleeding edge Google Glass AR glasses. The tech works just fine and seems useful to boot. It just turns out that it is not quite useful enough for people to actually want to buy and wear Google’s glasses outside of very specific use cases; at least not yet.

Google Maps, on the other hand, is AR that has already found a natural place in our lives. It is a great example of how technology can fundamentally change our perception of the world around us, while staying out of the way. Google Maps adds a digital layer of information onto the physical world, full of useful information about our surroundings, and we have gradually become more dependent on this digital layer, to the point where it now is second nature. Meanwhile carrying a paper map, or even calling someone for directions, now seems strangely archaic.

An intriguing idea

This February Wired Magazine published a massive think piece on AR, written by the magazine’s founding editor, Kevin Kelly. The headline reads: “AR will spark the next big tech platform – call it mirrorworld”. The buzzword alarm goes off whenever some tech missionary combines the words next and big in a headline, but the idea Kelly delineates is an intriguing one:

“The mirrorworld doesn’t yet fully exist, but it is coming. Someday soon, every place and thing in the real world—every street, lamppost, building, and room—will have its full-size digital twin in the mirrorworld. For now, only tiny patches of the mirrorworld are visible through AR headsets. Piece by piece, these virtual fragments are being stitched together to form a shared, persistent place that will parallel the real world.”

This concept did not originate with Kelly. The term was first coined by Yale University computer scientist David Gelernter in his 1991 book “Mirror worlds”, where he wrote that this technology “will revolutionize the use of computers, transforming them from (mere) handy tools to crystal balls which will allow us to see the world more vividly and see into it more deeply”.

The vision of the mirrorworld is essentially a merging of augmented reality with the internet of everything, another ambitious tech prophecy that is taking its sweet time to come true. The IOE is the vision of a world where your bed, your refrigerator, your stove, your car, and your shoes are all connected and exchanging information. In a world where everything is connected the potential of augmented reality is vastly enhanced.

To understand what the mirrorworld would mean, it is helpful to consider self-driving cars. At present they are using cameras and other sensors to collect information from the world they operate in, meticulously building a digital model of the streets around them that their algorithms then struggle to make sense of. But they are also aided by the aggregated data that is collected, uploaded to the cloud and then accessible to other cars, for instance in the form of maps and information about the current traffic situation.

In an internet of everything scenario the cars on the street would be less dependent on making sense of the world through computer vision. Cars, bicycles, pedestrians, traffic signs, bridges and the roads themselves would be in constant communication with each other, sharing information and together creating fine-grained digital versions of the world – mirrorworlds if you like. AR eyeglasses, too, would be far more powerful than the current state of the art if they could instantly extract information from every little thing they were looking at.

A world built on ones and zeros

The vision of the mirrorworld is shared by many players in this fledgling industry. Magic Leap is one of the companies developing AR hardware to allow us to access the information layers in new ways. They call their version of the mirrorworld the “Magicverse”. Meanwhile, futurist author Charlie Fink calls it a world “painted with data”, and Microsoft’s Mike Pell likes to talk about spatial computing and “smart information” that presents itself precisely when we need it, based on its understanding of our location and context.

These visionaries are all referring to a vast new world built by ones and zeros that, with the help of AR and AI, alters the physical world around us. This mirrorworld – or whatever you choose to call it – is an exciting prospect. But the bleak reality is that there will never be a single, shared mirrorworld. Instead, there will be many mirrorworlds.

Digital layers are added to our world at a rapid pace. In just a few decades mobile phones have altered our sense of place, space and time. We tend to imagine the next technological milestone to be amazing and transformative while what we already have seems boring and routine. But it can be helpful to zoom out from the here and now, and imagine what we would think of today’s smartphones if they were presented to us in the 1970’s. From that viewpoint we are carrying around tiny miracles of human innovation in our pockets, and they happen to be amazing augmented reality tools. In the words of cyberpunk author William Gibson: the future is already here – it is just not very evenly distributed.

Today, the overwhelming majority of the world’s population does not own a smartphone. As more digital layers are added to the world, there is no reason to believe that they will be accessible to all, nor distributed equally. We will be piecing together shards of these mirrorworlds in different ways, depending on what we want and what we can afford.

Every powerful tech company in the world will want to own, control and profit from these mirrorworlds, which means there will be competing shards or layers. Alphabet – the parent company of Google and Waymo – is particularly well situated to rule these worlds. They are leading the AI race, and with Google Street View cars and Waymo’s fleet of self-driving cars they are documenting the physical world, inch by inch. With the help of Android smartphones, they can track smartphone users as they move not only on the web but through the physical world as well. Google Maps, as mentioned before, is an impressive digital recreation of the planet, with maps of varying definition covering the entire globe. In some places the granularity is no greater than showing the names of roads, in other places you can effectively walk the virtual streets of cities, and even find your way inside building complexes like airports and shopping malls.

All are investing heavily

As amazing as this is, Google Maps is just in its infancy. 15 years ago, it did not exist. Try to imagine what it will be 20 years from now.

Alphabet competitors such as Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Baidu, Wechat and Tencent are behind at this point, but they are all investing heavily in technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality and artificial intelligence. As competing mirrorworlds collide, we will see reality fracture into different layers and experiences. If you think this sounds strange, I can reassure you: it will soon seem familiar, even unremarkable. In fact, it is already happening. Imagine three people moving through a city. One is a foodie, one is a Tinder user, one is a Pokémon Go player. The way they experience the city will be very different from each other: the foodie with an eye on the interactive map leading the way to the hottest restaurants and microbreweries; the Pokémon Go player immersed in the hunt for “pokéstops” visible only to those with the app active; the Tinder user keenly aware of potential dates in the immediate vicinity. And then, of course, there is the rare flaneur who experiences the city au naturel, oblivious of the many layers of data available.

Philosophers have argued for centuries about the existence of an objective reality.

Philosophers have argued for centuries about the existence of an objective reality, whether or not we can perceive it and should expect that we share the same experience of it. Plato, in ancient Greece, believed that such a reality existed but that it was inaccessible to humans, who only perceive its shadow. Immanuel Kant followed in Plato’s footsteps two millennia later, distinguishing between objects as things-in-themselves and as phenomena, the latter being our perceptions of these objects, filtered through our sensibilities.

The prophecy of the mirrorworld is a grand one, a promise of enhanced access to and understanding of the world. But the most important takeaway here is this: As we integrate technology ever more intimately into our lives, our sensibilities are changing, and with them the very phenomena of objects around us. In the words of David Gelernter, tech now indeed helps us “see the world more vividly and see into it more deeply”.

Moving into the future, our shared experience of the world is coming apart, piece by piece, altered as it filters through a multitude of digital layers. To each his own mirrorworld, presented by Google or Facebook – and filled with highly relevant advertising.

Sam Sundberg

Freelance writer and Editor for Svenska Dagbladet since 2005

Years in Schibsted

11

My dream job as a child

Private investigator

Our future with AI calls for human visionaries

Our future with AI calls for human visionaries

AI is not an abstract future shift, but a set of practical tools here today. It is up to our human creativity to use them in ways that question established truths and move our species forward.

Many use the term ‘race’ when discussing current developments in AI. Yet a race is usually connected to a competition of speed, with contestants moving in the same direction, fighting each other towards a specific point. With AI we don’t have such a destination. There is no way of determining who gets ‘there’ first, since the product of our efforts is not a place but something as grand as the evolution of our species. To advance through this process, it is in due time we reflect on where we humans can create the most value.

A key weakness of AI is the fact that algorithms are inherently conservative. As they learn from data representing what has worked in the past, they are unlikely to pioneer in uncharted territories or celebrate emerging changes in culture. Let’s call it algorithmic shortsightedness – the inability to predict and celebrate how novel ideas, content or products perform.

The basis of their shortsightedness is that algorithms are only as good as the data they are trained on. Using insufficient, biased or faulty data about past successes to inform strategies and products for the future is thus risky business, and in recent years we have seen many examples of how it can hurt big corporates and startups alike. Radicalizing echo chambers, biased hiring tools, racist image recognition services, oppressive credit scoring tools – the list goes on and on, and the outcome often hurts those at the bottom of social hierarchies the worst.

We need visionaries

Algorithms are incredible tools for finding solutions when there is a pre-decided number of alternatives, regardless of their number. By definition they cannot think outside of the box(es) they are given. Luckily, humans are skilled at doing just that! Our ability to question established truths has been integral as our species has moved through time, and in this age of AI we should celebrate the skills such reflection requires.

In commercial settings, we need to update how we approach and value skills in domains like philosophy and art. To win in the age of AI, we need visionaries who are cultivated and open-minded enough to be able to view a different kind of world! Safe bets may feel appealing in times of global instability, but we have to dare imagine complete novelties to really power our businesses through AI.

It is not AI alone, but the combination of it and visionary humans that will bring the real revolution. This is similar to past waves of mechanization and industrialization; it was not the mere innovation of e.g. the automobile that altered the course of humankind, but the pairing of such a new tool with humans deciding where to take it. Let us not underestimate our opportunity to now shape AI in ways that benefit society.

Artificial Intelligence may be the future, but it doesn’t know it better than any of us humans. Let’s not leave the future for algorithmic systems alone to decide. Our historical data isn’t exciting enough for the rest of the time to depend on in.

Agnes Stenbom

Associate Product Manager in Machine Learning

Years in Schibsted

1

My dream job as a child

Editor of a newspaper

A picture is worth a thousand words

A picture is worth a thousand words

What if we in the future will only use photos when searching for things online? Image recognition is already improving a lot of services dramatically – some at Schibsted’s marketplaces.

Long before we could read or write, visuals and sounds were the only way of communication, i.e. gestures, body language and simple drawings in the sand, accompanied by some sweet “Uh ga Chaka”. In fact, writing systems with letters are merely abstractions of the visual communication that preceded them. One could argue that the written language has been a temporary means of communication while we wait for technology that can process and derive meaning from the incredible amount of information that visual formats (e.g. photo or video) carry compared to written words. That technology is here and it’s here to stay. Its name is image recognition (or computer vision) and Schibsted is already experimenting with it.

Up until recently, computers have only been able to “see” our world. With recent advancements in artificial intelligence, however, computers are now able to “interpret” and “understand” what they “see” – sometimes even better than we do! Computers used to be like newborn babies: Most have eyes which give them a glimpse of the world around them. Yet, it’s not before they learn to focus their vision that they start to truly comprehend what is around them.

Speed and scale impossible for humans

Video is just a fast sequence of images, images are data and these data are processed through algorithms that are trained to recognize patterns in those data. Different models can return different results depending on the desired use case. With cloud computing and high resolution imagery, computers can now perform tasks at speeds and scales that are impossible for humans; detecting nanometer deviations in a production line; tracking and predicting hurricane impacts; guiding autonomous vehicles through traffic; real-time digital translator on your trips around the world (ref. Google Translate); to find an individual among hours of video in a matter of minutes.

This will inevitably alter how we go about our daily lives as products and services leverage the huge potential in computer vision.

This is particularly interesting for marketplaces that are about matchmaking (a.k.a. liquidity) – bringing buyers and sellers together and facilitating a transaction between them. Amongst other things, image recognition can improve the quality of data by enriching ads with metadata, and the user experience by enhancing the search and discovery part of the customer journey.

There are multitudes of applications of computer vision from hosts of providers. Companies like Google, Amazon, eBay and (in particular) Pinterest have been working on their own solutions for image recognition, and all of them have lately scaled their investments into the technology. Schibsted also has some features that are already live and more are in the pipeline. Below are some of our favorite and most promising use cases within marketplaces.

Visual search

Our culture is already dominated by visual stimuli. Half of the human brain is (directly or indirectly) devoted to the processing of visual information (MIT, 1996). It seems only natural that search and discovery starts with an image. Visual search, i.e. search with imagery as input (as opposed to text), enables quicker search and more accurate results, catering to a better user experience in the search and discovery phases. This drives better matchmaking. Notably, Pinterest recently integrated Shoppable Pins directly with their visual search (Pinterest Lens) which could disrupt the traditional customer journey as we know it. Finn Torget has an image search (beta) on web – try it: finn.no/bildebeta

Category suggestions

Sometimes the sellers on our marketplaces place their ads in the first category that comes to mind and that category is not always the correct one. Albeit, one can always improve the category taxonomy, it could also be solved with smart suggestions based on image recognition. The category suggestion service of the Cognition team helps people select the right category for their ads during the classified ad submission. The user snaps a picture and the service provides suggestions for which category the ad could belong in. This removes friction and shortens ad insertion time, and ensures that ads are categorized correctly so they are easy to find. This feature is in production on Blocket.

Recommend visually similar ads

Image recognition can capture remarkably more facets of an image than what a human is able to articulate in a text search or what collaborative filtering (a common recommendation method) is able to account for. Thus, recommendations based on visual similarity can be more relevant, which makes it easier for a buyer to find exactly what she or he is looking for.

Another useful distinction between recommendations based on collaborative filtering versus visual similarity is that while the former tends to favor recently published ads (because of users’ behavior), the latter is often indifferent to the age of the ads (as similarity trumps age). This means recommendations based on visual similarity can give new life to older ads and hopefully provide them a new owner.

This feature is in production for all categories on FINN Torget.

Metadata enrichment

We know that some sellers ”forget” to include significant information about their object in the ad. Meanwhile, some buyers find it hard to find exactly what they are looking for even though it might exist on the marketplace. We can cut out the humans from the equation and jump straight to automation. Image recognition allows us to populate an ad with additional metadata based on the uploaded image(s) which makes the ad more ”searchable” and consequently easier to find. That way we boost liquidity – and both the seller and buyer are happy! What’s more, it could even help valuate an object and auto-generate relevant alt text for images which is great for accessibility and SEO. A working prototype was built using Google Cloud Vision’s API during FINN hack days in May 2019.

Cropped visual search

Over the past few years though, we have seen a rise of inspirational platforms like social media and Pinterest. Instagram and Pinterest are incredibly good at monetizing the search for inspiration. So why is Schibsted not doing the same? We know that many of our users hang out on our real estate ads for inspiration. What if we could help them find the things they like in those images (e.g. that retro sofa or designer lamp) on our generalist marketplace or at Prisjakt? Food for thought. Bon appetit!

Arber Zagragja

Product Manager, Tech Experiments

Years in Schibsted

3

My dream job as a child

Architect for Snøhetta

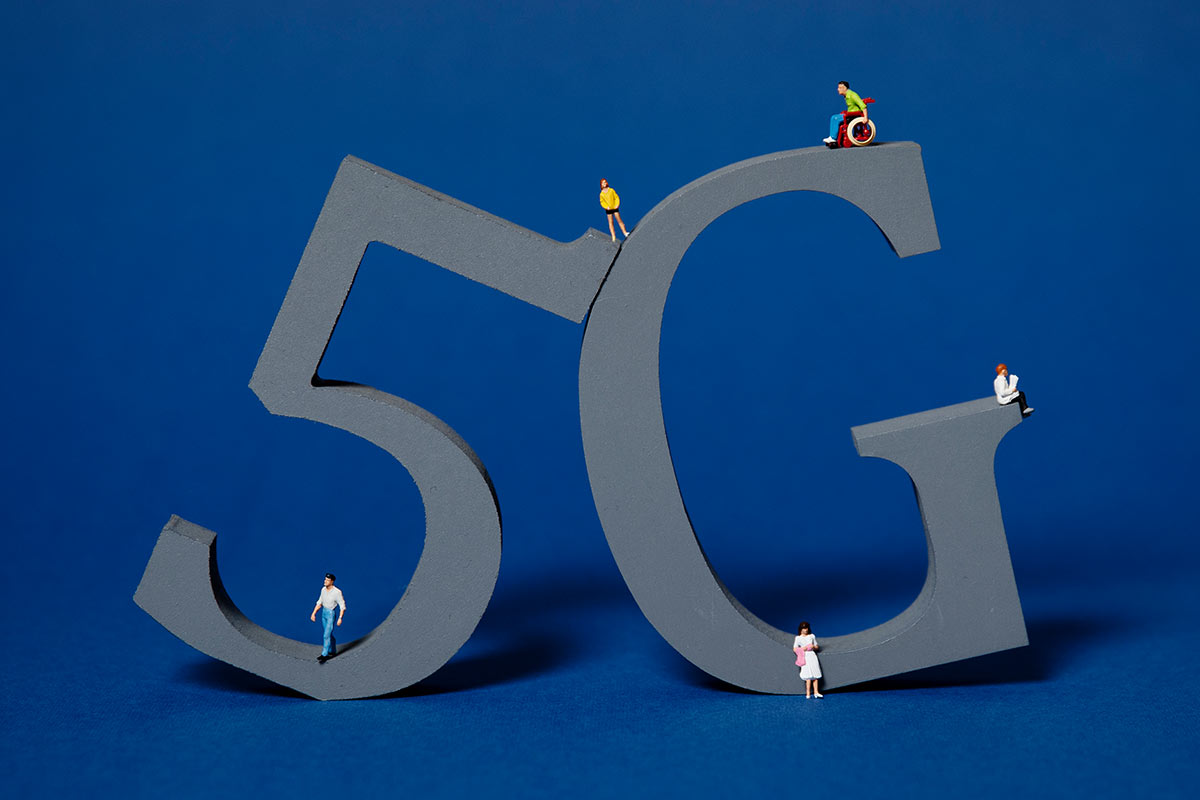

5G – A miracle yet to come

5G – A miracle yet to come

The world’s data traffic has been rapidly increasing for the past decades and the number of connected devices is growing by the day. This creates the need for a faster, more stable, and more developed cellular network. But is 5G ready to come and save the day?

You may have heard about 5G – the technology that is expected to create new opportunities for mobile networks as well as lay the foundation for the future of IoT (Internet of Things). 5G stands for fifth-generation cellular network technology. When running smoothly, 5G could operate as much as ten times faster than 4G, reaching peak speeds of 20 GB per second.

An often-used example of what this could mean for the average consumer is that a movie that would take five minutes to download with 4G only would take about 30 seconds to download using a 5G connection (if nothing else, handy when you are about to board a plane and find out there is no in-flight entertainment).

Reducing delay

5G would also have a significant effect on reducing network communication delays, called latency. Put simply – no more annoyingly slow video calls. On 4G, the latency for a video chat is around 10.5 milliseconds (ms). With 5G, it is less than a tenth of that, around 1 ms.

It almost goes without saying that this kind of increase in mobile speed would have the potential to disrupt a lot of industries. Some that are often being mentioned are healthcare, manufacturing, automotive, retail and entertainment. Since 5G would allow devices to communicate with each other with almost no lag, the technology could, for example, open up for things like wireless VR experiences and more reliable driverless cars.

Like its predecessors, 5G would likely mean a lot of new opportunities also for the news industry. Not too long ago, The New York Times launched a 5G Journalism Lab. Although its vision has been called a bit vague, it includes both new internal tools and upgraded experiences for audiences, such as more and better AR and VR immersive experiences.

The most revolutionary impacts 5G will have on news media, however, are probably the ones publishers can’t anticipate today, Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab has argued. It could be things like having reporters that are constantly streaming from the field, the ability for reporters to access their colleagues’ raw video feeds and creating “The Newsroom of Things” where cameras could be set up at different events and stories be generated automatically.

Operates on the cloud

There are still a lot of unsolved (and according to some, perhaps even unsolvable) challenges facing 5G. If we allow ourselves to get technical for a minute, 5G is what is called a software-defined network. This means that instead of using cables, it largely operates on the cloud. 5G uses what is called “millimeter waves”, or short-wavelength radio signals. On the upside, this dramatically increases the bandwidth and makes it possible to cram more data and accommodate more users. On the downside, short wavelengths cannot travel long distances and have a hard time penetrating things like walls.

This means 5G will require new phone hardware, a lot more base stations to maintain connectivity, and new phone and network designs. Not to forget, additional hardware in your phone probably means less space for battery and more power usage. For now, experts have said they expect 5G phones to be thicker, more complicated, use more energy, and cost more money. The general recommendation has therefore been to not rush to upgrade, but rather to check back in 2020 when 5G is said to begin to roll out globally.

5G has already been launched on a small scale in the US and South Korea. China and Japan are not far behind, and tests have begun in European cities such as London, Stockholm, and Berlin. But even if the expansion of 5G has begun, it is hard to say when it will replace 4G. As we have learned, there are still some minor (and major) obstacles standing in the way between you and that ultra-smooth experience 5G promises.

Mikaela Åkerman

Industry Editor, Upnext

Years in Schibsted

6

My dream job as a child

Scientist

Logistics will bring you breakfast

Logistics will bring you breakfast

In Norway you can get your breakfast and online purchases delivered by your newspaper carrier. The secret behind this is logistics IT and Distribution Innovation – a company within the Schibsted family.

As readers of printed newspapers are getting fewer, the luxury of getting the paper on our doorsteps every morning seems threatened. Turns out it’s a great business opportunity –

In Norway several new services are launched to consumers and businesses, with the help of the newspaper distribution network, Like Morgenlevering (the breakfast) and Helthjem (the parcels).

The decision to develop and launch Morgenlevering.no in 2015, was based on the idea of “moving the newsstand to your doorstep”. The super-fast newspaper delivery network was already there – the recipe for unlocking the opportunity was teaming up Logistics IT with operations, adding an entrepreneurial mindset and a splash of madness.

Initial success was limited, but the service found its purpose when a local baker saw the potential in using it as a platform for selling his freshly baked goods. In 2019, Morgenlevering is a separate company that offers fresh bread and pastries, cakes, flowers, juices and magazines – delivering more than 1.6 million products to homes in the greater Oslo area, in Bergen, Stavanger and Trondheim.

Logistics and Mobility are industries where technology over the past five years has enabled tremendous development. Unicorns like Uber (taxi), Doordash (food delivery), Instacart (groceries) and Pillpack (pharmacy) are looking at old problems in a new way and leading the way.

160 years of delivering newspapers

But new ideas do not always come from new companies. Schibsted Distribution has 160 years of experience delivering newspapers; a highly perishable product, which comes off the press at midnight, and needs to be on consumers’ doorstep before 7 am. In 2001 Distribution Innovation was born in the same family and has since then been a pioneer in digitalizing logistics.

“Distribution Innovation was created in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble bursting in the Spring of 2001”, says CEO Tone Løyland. “It became important to use new technology for something that could achieve financial results. At the same time, we found that the mobile internet could already solve some of the operational challenges the newspaper distribution was facing”.

DI created and launched one of the first mobile business applications in the Nordic countries, the DI Electronic Delivery Guide for last mile carriers. This was made possible by heavy user involvement, and a process which facilitated cooperation across competing newspapers from the very beginning.

By creating software that has become the industry standard, DI has also managed to win distribution customers across Sweden and Finland and now currently manages more than two million deliveries, across distribution routes that roughly span the distance from Earth to the Moon – every night. With a scale like this, it goes without saying that technology has contributed greatly to optimizing and driving efficiency in delivery. From the start, the system has also been developed to allow delivery of more than just newspapers, and to build third-party end-user services on top of the distribution network.

Entered the e-commerce logistics market

In 2014, as the decline in printed newspaper volumes was accelerating, and most of the cost-cutting potential was realized, Schibsted Distribution decided to pursue the rapidly growing e-commerce logistics market. The idea was to have the network and the capabilities to offer home delivery of small parcels – creating new income based on the existing distribution structure. A common end-to-end system across Norway was a critical piece of this puzzle.

“With the DI system in place across the network, we could focus on building the market side and setting up the back-end of the value chain. DI’s solutions have developed along with the growth of our parcel volumes,” says Cathrine Laksfoss, CEO of Schibsted Distribution.

In 2015 Schibsted joined forces with Norwegian media peers Amedia and Polaris media under the common brand Helthjem (“All the way home”) – establishing a national distribution network of around 4 000 carriers covering 90 percent of Norwegian households 6-7 nights per week. This would not have been possible without a common IT system and a joint goal: To maintain efficient distribution despite falling volumes of traditional products.

“We find it counter-intuitive that people go to a store to pick up their online shopping. Research shows that 70 percent of shoppers would like to get their parcels delivered at home, whereas less than 25 percent actually get it,” says Anders Angen, CEO of Helthjem Netthandel (HHN).

More and more online retailers seem to agree. HHN is the fastest growing ecommerce logistics provider in Norway, targeting 3.5 million parcels in 2019 after doubling volumes every year since 2016.

“Cooperating closely with DI has been crucial in building our service – both in terms of quality in last-mile delivery and integrating customers’ systems with our own logistics platform”, says Angen.

To build the consumer position, and to tap into the circular economy, HHN launched the Megtildeg.no service in 2017. This is a consumer to consumer delivery service, using the Helthjem network to transport parcels from doorstep to doorstep. Megtildeg was developed together with DI and has also been adapted for the online used bookstore Bookis and FINN’s FINNLevert service.

Continuing to explore new tech

DI have also played an instrumental part in developing the app and other systems supporting Schibsted Distribution’s brand-new shipping subscription, SVOSJ. This is a platform which links online retailers to consumers through Helthjem shipping.

“DI’s know-how of all our distribution and logistics systems, combined with front-end usability expertise, has been extremely valuable in the development of the SVOSJ service,” says Simon Vestvik, project manager for SVOSJ.

“Enabling new business development and testing new technologies are the core of DI,” says Frode Finnes Larsen, CTO of DI.

Over the past couple of years DI hackathons have developed secure C2C logistics based on blockchain technology, the first working Google Assistant based voice shopping service in Northern Europe for Morgenlevering and integration of digital locks in the carriers’ Electronic Delivery Guide. DI was also the first player to use Telenor’s brand new IoT-network (Narrowband IoT) experimenting with sensors in containers to collect clothes.

“In this spirit DI continues to explore the newest technologies to learn and identify new potential services and applications”, says Larsen.

DI have claimed the position as the Nordic industry solution for distribution of newspapers, magazines and parcels – through the media distribution network. To stay relevant, DI needs to provide the carriers with technology that will help them in their work to meet new demands, delivering high quality distribution technology combined with new tools like augmented reality (AR), voice commands, image recognition and automation, to handle even more complex services to customers within and outside of the Nordics. The shift towards parcels as the dominating product in the network will be a demanding process for all parties, and the focus for DI will be smart use of technology to enable profitable services for consumers and businesses.

“DI has always focused on collaboration, and this will be increasingly more important in the coming years. Collaboration across borders and industries, empowered by smart use of technologies and efficient distribution networks can create unique and valuable services for both consumers and businesses. And that will be in high demand in the coming years”, says Tone Løyland, CEO of DI.

Morten Gamre

Sales and Marketing Manager

Years in Schibsted

4

My dream job as a child

Musician/pop star

Meet our people

Meet our people

Juha Meronen, CEO at Tori in Finland, truly believes that marketplaces can help changing peoples’ behavior towards a more circular society. At Tory they have many exiting ideas on how. Meet him, Nina Felixsson, Patryk Kurczyna and Simen Eide, some of our Schibsted people.

What if there was an index on the secondhand value for products? And what if that would make people buy more high-quality goods and resell them when they don’t need them anymore?

“We have the data on value and quality to do such an index, and I truly believe that marketplaces for secondhand trade can change consumers’ behavior towards a more circular society,” says Juha Meronen, CEO at Tori,

Schibsted’s marketplace in Finland. At Tori they have concluded that a circular economy is much more than recycling and the flow of material. They are now looking more into the inner circle of this.

“It’s about making people buy things that last longer, repair and modify and then change ownership. If this became a habit it would totally change the game.”

To get there, consumers need to know why they should change their habits – the index showing the secondhand value could be that reason. If a childrens’ chair is still worth 70 percent of the original price when sold on Tori, parents that normally would by a cheaper chair might consider buying the more expensive one if they know they will get this much money back when reselling it.“We have this information, we just need to get it out,” says Juha. Yet. Tori has now initiated a Schibsted project to develop this index.

But Tori has more ideas to make us buy fewer new products – this is somewhat more advanced: what if all the things you own were listed in an inventory. Or perhaps all the things in Finland? If we knew the value of this, it might make us realize that we should use all the things we already have – instead of buying new stuff.

“We need to start thinking differently, and young people are already leading the way. We hear young people saying that buying new things is not in line with their personal brand.”

Years in Schibsted: 5. My dream job as a child: ather Christmas, a priest or a queen

Cords makes designers cooperate

A new UX design system is fundamentally changing how updates and new features can be implemented and shared on Schibsted’s news brands’ digital platforms. It’s so unique that design teams from both Canada and Belgium have already visited and been in contact with the media product and tech team to learn about it. Cords – Core news product design system – was created by UX lead Nina Felixsson and her team.

“We have made a ‘white label’ product that any brand can use and apply their identity to,” explains Nina.

Cords is a framework for design and artwork that contains guidelines for processes and how to work on design and user experience – and it has its equivalent in code. To be even more specific: on an article level it contains design for all components – like headline, media player, image gallery, text etc. But perhaps most important – it has also changed the way the design teams work.

“Cords has become a reason to collaborate on UX design across all our news brands. Now we have weekly meetings to discuss what’s next on the agenda and what we need to improve,” says Nina.

Years in Schibsted: 6. My dream job as a child: Professional football player with Juventus F.C.

A project bigger than GDPR

Patryk Kurczyna joined Schibsted in the first internship program at Schibsted’s tech hub in Poland. Now, six years later, he and the rest of the payment team have launched one of the most complex projects so far: they have aligned Schibsted’s products and systems to the EU Revised Directive on Payment Services (PSD2). We all know about GDPR – the payment directive is even more complex.

It’s all about customer authentication – making sure that you are you when you pay for something online. Now all users are required to authenticate themselves in at least two different ways – this of course means that all services charging users need to make this possible. The payment team in Poland has worked with many stakeholders within Schibsted.

“We had to migrate four million payment methods into a new system in a seamless way. All the users will still use the same payment cards – but we use another system. And at the same time, we had to do it in a fully transparent way,” he explains. So far everything has gone well.

“We have been able to maintain all payments and our clients within Schibsted are onboard.”

Years in Schibsted: 4. My dream job as a child: A combined jumbojet pilot and a developer

Algorithms still have to learn a lot

You might think that all the algorithms that control our digital flows and the things we see online have figured out how we humans work. That is not the case at all.

“The exciting thing is that people are unpredictable.”

Simen Eide is developing features created from machine learning and AI at Schibsted’s Norwegian marketplace Finn. Strong focus areas at the moment are recommendations and personalization.

“So far we have become good at showing people what they have been looking at earlier on the site. The challenge now is to create algorithms that can predict how peoples’ behavior develop, based on interactions – to understand what happens after we’ve shown you a certain picture,” Simen explains. “We know so little still – the potential in this field is huge.”

The good thing is that it’s a very transparent field to work in – experts, universities, and companies are sharing knowledge and results to a large extension.

“The cooperation make it very exciting and we’re getting better all the time and on thinking in different ways to solve the challenges.”

Tech trends in short

Tech trends in short

These are the key takeaways from Amy Webb’s Future Today Institute Tech Trends Report 2019. The report contains detailed analyses of 315 trends, based on quantitative and qualitative data.

The Big Nine

There are nine big tech companies – six American, and three Chinese – that are overwhelmingly responsible for the future of artificial intelligence. They are the G-MAFIA in the US: Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, IBM and Apple. In China it’s the BAT: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. Just nine companies are primarily responsible for the overwhelming majority of research, funding, government involvement and consumer-grade applications. University researchers and labs rely on these companies for data, tools and funding. The Big Nine are also responsible for mergers and acquisitions, funding AI startups, and supporting the next generation of developers. Businesses in the West will soon have to choose AI frameworks and cloud providers – likely Google, Amazon or Microsoft – a decision that will be extremely difficult to reverse in the future.

Privacy is dead

One persistent theme in the 2019 report is surveillance. Whether it’s how hard we press on our mobile phone screens, our faces as we cross an intersection, our genetic matches with distant relatives, our conversations in the kitchen or even the company we keep, we are now being continually monitored. Just by virtue of being alive in 2019, you are generating data – both intentionally and unwittingly – that is mined, refined, productized and monetized. We no longer have an expectation of total privacy. At least not like we’ve known it before. Companies that rely on our data have new challenges ahead: how to store the vast quantities of data we’re generating, how to safeguard it, how to ensure new datasets aren’t encoded with bias and best practices for anonymizing it before sharing with third parties.

China continues to ascend

China is pushing ahead in many different fields. It has launched a space race with ambitions not just to return humans to the moon, but to build indoor farms and livable spaces on the lunar surface. It is making bold advancements in genomic editing, in humans as well as in livestock and produce. Through its various state initiatives, China is building infrastructure and next-generation internet networks across Southeast Asia and Latin America. It is setting the global pace for air quality, carbon emissions and waste reduction. China’s electric vehicle market dwarfs every other country in the world. All of that in addition to China’s significant investments and advancements in artificial intelligence. No other country’s government is racing towards the future with as much force and velocity as China. This means big shifts in the balance of geopolitical power in the years ahead.

Lawmakers around the world are not prepared to deal with new challenges that arise from emerging science and technology.

VSO is the new SEO

About half of the interactions you have with computers will be using your voice by the end of 2020. Whether you’re talking to a smart speaker, or your car’s dashboard, or your mobile digital assistant, you’ll soon talk more often than you type. As content creators venture into spoken interfaces, publishers and other companies will soon be focused more on voice search optimization (VSO). The emergence of VSO affects scores of industries: advertising, hospitality and tourism, finance and banking, retail, news and entertainment, education and more. This means opportunity: there’s an entire VSO ecosystem waiting to be born, and first movers are likely to reap huge windfalls. But it also signals disruption to those working.

Data records are coming

One probable near-term outcome of AI is the emergence of a “personal data record” or PDR. This is a single unifying ledger that includes all of the data we create as a result of our digital usage (think internet and mobile phones), but it would also include other sources of legal records (marriages, divorces, arrests); our financial records (home mortgages, credit scores, loans, taxes); travel (countries visited, visas); dating history (online apps); health (electronic health records, genetic screening results, exercise habits); and shopping history (online retailers, in-store coupon use).

AIs, created by the Big Nine, would both learn from your personal data record and use it to automatically make decisions and provide you with a host of services. Your PDR would be heritable – a comprehensive record passed down to and used by your children – and it could be temporarily managed, or permanently owned, by one of the Big Nine. Ideally, you would be the owner of your PDR, it would be fully interoperable between systems, and the Big Nine would simply act as custodians. PDRs don’t yet exist, but there are already signals that point to a future in which all the myriad sources of our personal data are unified u nder one record provided and maintained by the Big Nine. In fact, you’re already part of that system, and you’re using a proto-PDR now. It’s your email address.

Read the interview with Amy Webb: Public data is a hidden treasure

Hacking The Code of Aging

Hacking The Code of Aging

Immortality is soon within humanity’s collective grasp. Scientists warn of overpopulation, class war, and inequality in the wake of growing life spans. But we’ll have time to figure it out.

“If you had to choose between living forever, or having children, what would you pick?”

The question from my friend annoyed me. I had talked enthusiastically about overcoming death for years but never reflected on the price I was willing to pay for eternity. If there was a way for me to be immortal, but it for some reason meant I had to give up the ability to have children, what would be more important? As we were having the existential conversation over breakfast, the morning news show on TV serendipitously talked about the growing human life expectancy. “Some say the first person to live to a thousand years has already been born,” the TV host said, and the doctor who was being interviewed nodded. “Some argue that, yes.”

I was initially fascinated by the prospect of living forever when I had just moved to California to work as a freelance tech and science reporter a few years ago. I had read about a man, Dr. Joon Yun, who had made it his mission to “hack the code of aging”. The former Stanford-doctor-turned-investor was giving out a million-dollar prize to whoever could advance the research in a substantial way. When I arrived at his office in Palo Alto for an interview a team of five people was waiting for me in a gigantic conference room; his assistant, a two-person private media team, a business partner, and Dr. Joon Yun himself. This guy was clearly serious about everything he set his mind to.

What about overpopulation?

From that day on, I couldn’t let go of the idea that dying didn’t have to be something imminent and unavoidable. Joon had introduced me to a number of people who didn’t deem the undertaking of putting an end to aging impossible – or at least pushing the deadline dramatically. Rather, they were all surprisingly convinced it could be done within our, or at the very least our children’s, lifetime. Obviously, there are questions and potential problems that arise with the idea of humans staying around for decades and decades. What about overpopulation? Will living for hundreds of years or more undermine our drive and appreciation of life? Will the technology be available to everyone?

The idea of living forever is not in any way new. Ever heard of the Greek myth of Tithonus? He was a prince of Troy and a lover of the goddess Eos. In fear of losing her lover, Eos begged Zeus to grant Tithonus immortality. But she forgot one thing; to ask that Eos also would have eternal youth. Tithonus kept aging until he had shrunk to the size of a grape, unable to die, illustrating a fear of never ending old age that goes back thousands of years.

In Silicon Valley, immortality is something that can’t be bought for money (yet). But it is safe to say that prolonging life has become an obsession for some. Ray Kurzweil is a renowned computer scientist at Google, known for his books on singularity and his resolute fight against time. The 70-year-old allegedly takes hundreds of supplements every day for anti-aging and health purposes. I once listened to Kurzweil speaking at a medical conference where he talked about uploading our brains to the cloud and having nano robots cleaning our blood. Not surprisingly, futurist Kurzweil has signed up for cryonics (low temperature preservation of human corpses) in hope of there being a way to bring him back to life in the future in case he dies.

Overpopulation won’t be dramatic

So, what are the most promising methods of extending the human lifespan? And who are the people most likely to make it happen? At the Google research and development company Calico in California, scientists are trying to come up with possible solutions that could enable people to live longer and healthier lives. For these visions to succeed, however, “an unprecedented level of interdisciplinary effort and a long term focus” will be needed, according to the company. The same conclusion was reached in one of the meetings I attended during my time in Silicon Valley. Representatives from some of the most influential companies and institutions in the US had gathered to talk about the possibilities and challenges that the endeavor of curing aging entails.

According to Sonia Arrison, author of the book “100 Plus”, overpopulation won’t be as dramatic as you might expect. Population growth is mostly driven by birth rates, not death rates. When one person doesn’t die, it is only one person. But when people have children, they might have one, two, three, four, five… Equality might be a bigger concern, Arrison argues. The wealthier will always get new technology first. But what happens if there is a huge time lag between the wealthy and the poor getting access to the therapies, and the gap between the highest and the lowest average life expectancies widens from 40 years to a century or more? “There could be civil war. This is something that people could literally fight for their lives for”, Arrison says.

“Senescent cells have been described as the ‘zombie cells’ of our bodies.”

When it comes to the methods for extending human health- and lifespan, there are a number of scientific approaches. If we narrow it down to some of the discoveries that are about to begin human trials in the near future and that could benefit people who are alive today, there are few worth mentioning. Senescent cells have been described as the “zombie cells” of our bodies. Each time a cell copies itself, it loses some DNA at the end of the chromosomes. To protect our genetic information, chromosomes have long “useless” bits of DNA at the ends, called telomeres. In some cells, however, these will eventually run out. Your cell is now a zombie, hanging around, harming tissue around it. The older we get, the more senescent cells we collect. But what if we could get rid of these toxic remnants?

When scientists genetically engineered mice so that they could destroy their senescent cells, the mice lived up to 30 percent longer than average mice. We can’t genetically modify all cells in a human (there are about 70 trillion), but there might be a way to kill the damaged cells without harming the healthy ones. Cells like senescent cells underproduce a protein that tells them when it is time to die. When scientists injected this protein into mice, it killed about 80 percent of all the senescent cells with almost no other casualties. Today there are a number of companies looking to come up with anti-aging treatments involving senescent cells.

The first anti-aging pill

Another hot candidate is NAD+. It is a coenzyme that plays a central role in the metabolism and energy production of living organisms. At the age of 50, we only have about half as much of it as at the age of 20. Low amounts of NAD+ has been linked to various diseases such as skin cancer, Alzheimer’s and MS. When mice were given a substance that turns into NAD+ in the cell (NAD+ can’t enter the cell itself), the mice showed a higher ability to repair their DNA and also had a slightly increased lifespan. If human trials show similar effects, some believe NAD+ could become the first human anti-aging pill.

Lastly, we have stem cells. These are cells with a unique ability to develop into specialized cell types in the body. You can think of them as little factories that produce fresh cells to various body parts. Our stem cells decline with age, and therefore, so does our ability to repair ourselves. When scientists injected stem cells from baby mice into the brains of middle aged mice, the fresh cells reinvigorated the older stem cells and improved the mice’s muscle and brain function. When fresh stem cells were injected into their hearts, the older mice were able to exercise 20 percent longer.

More funding is needed

There probably isn’t a quick fix to cure aging; no secret potion or single magic bullet. And as we all know, humans aren’t mice. There are no guarantees that these and other therapies will have the same effects on us. For scientists to really investigate the limits of the human health and lifespan, the field needs more attention and funding. And to those who feel it is simply unnatural to manipulate the way of nature: isn’t anything that humans can achieve natural in some way? Is it not in our instincts to push our boundaries? What about the question from my friend about what I would pick between eternal youth and bringing a child into this world? Hopefully, there is no rush. If all goes well, I will have at least another couple of hundred years or so to figure it out.

Teaching robots how to write

Teaching robots how to write

Reporters at Aftonbladet have been producing articles for close to 188 years. Now comes one of the biggest revolutions in the history of Schibsted. From now on robots will write and offer readers hundreds of articles every day. Sweden’s biggest media house is increasing its service to readers with this latest technology.

A text robot will be producing content for the coverage of traffic and weather in addition to creating texts for the football coverage in the section Sportbladet. This project is carried out in cooperation with United Robots, which is leading in artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language generation (NLG) in producing publishable articles using large data sources.

The new service will work as a complement to the traditional journalistic work and will create content to an extent never reached before at Aftonbladet. The automated writing of texts means that there is no limit to how many texts can be produced in a day. Furthermore, the automatically written articles can mean more time for the paper’s reporters to concentrate on the biggest and most important stories as the robot deals with more mundane matters.

The first section to use the new technique will be the reporting on traffic and weather together with football pieces. The traffic robot will produce articles about situations and warnings from roads all over the country and report estimated delays that follow. Together with the texts, the robot will send a satellite picture highlighting trouble spots.

Taught by journalists

But how can the robot tell us what is happening on the roads of Sweden?

This is how it works:

- An incident or a blockage occurs.

- The state-run Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket) sends data to the robot containing facts such as type of incident, number of vehicles involved, GPS coordinates and at what time the road is estimated to be clear again.

- The robot creates a text using the wording it has been “taught” by Aftonbladet journalists to sound as natural as possible. In order for the texts to be varied, the robot can describe the same incident in several different ways.

- The text is filed to Aftonbladet and is automatically published on aftonbladet.se. When there is a major incident, a push notification can be automatically sent.

As for the weather reporting, the service is based on warnings issued by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI). With the help of the robot service, Aftonbladet will be able to provide more content and a wider coverage. That means better opportunities to personalize products and, with geo positioning, increasing possibility of giving readers relevant information. The robot can also facilitate the work in the newsroom by issuing alerts drawing attention to major events such as accidents with several vehicles involved. Algorithms will analyze all the available data looking for deviations, connections and events that could lead to a wide coverage and alert the newsroom.

When the whistle blows

Text robots were used already in the spring of 2018 as Sportbladet increased the depth and width of its Premiere League reporting. Traditionally, the coverage in Sportbladet has consisted of live reporting from matches together with texts, mainly about the top teams. With the help of the robot, and with its global sports data source Sportradar, Sportbladet can now publish articles at the moment the referee blows the final whistle – from every game that has been played.

Together with TV highlights from Viasat and match facts from Sportbladet’s goal service, it gives the reader the chance to read about his or her team’s match instantly. “With all the deep data we have from major leagues such as Premiere League, the robot knows a lot about what has happened during the match”, says Sports Editor Pontus Carlgren. “That, together with the speed a robot offers, gives our coverage a new dimension.

Thanks to the possibility to subscribe to texts through the follow function on the site, supporters won’t miss a single article about their team”, Carlgren says, adding that “The fact that the robot produces texts that are finished at the final blow of the whistle,will give our knowledgeable reporters and columnists more time to work on thought-through articles and columns for the benefit of our readers.”

Changing the view on reuse

Changing the view on reuse

In Belarus, Kufar has changed the perception of secondhand trade from the Soviet days. Now they are also sharing insights and knowledge to help build businesses.

In the 80s, when Belarus was a part of the Soviet Union, buying stuff directly from private people was almost the only chance to get a pair of jeans, a tape recorder or a pack of imported cigarettes. At that time, you could barely find anything decent in the stores due to the shortage of goods, including clothes, household products or even groceries.

As a consequence, the concept of buying directly from a private person was so popular that there even was a group of people named “fartsovshiki”, who earned money by finding and reselling rare – primarily foreign – goods at a high price. Actually, people were doing this during most of the Soviet era – they made deals starting in the late 40s, all the way through to the 70s. And in the 80s, when the iron curtain started to fall, and more people got a chance to travel abroad, the movement became widespread.

In the 90s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, buying from private sellers was still the only chance to find a lot of goods. Financial crisis, currency inflation and budget shortfall gave rise to a secondhand economy. When salaries dropped, few people could afford to buy brand new items. Plus, it was not easy to go shopping: store shelves were empty, and food coupons were used instead of bills. After a decade, memories of the crisis were still vivid. Consumption of secondhand goods was associated with poverty and tough times. So, at the dawn of the millennium, people rather bought cheap, new mass-produced stuff, instead of quality items with a history.

Traffic increased by 70 percent

At this point Schibsted came to Belarus with an ambitious goal: to conquer the local market, and to change the perception of secondhand trade and classified marketplaces. The platform was set up in 2010 and despite the fact that it was launched by just a couple of employees, Kufar soon became an important asset. “Our first office was in a flat. There was too much work and only three of us. And we were responsible for everything – from paying rent to creating design sketches”, says Gregory Lashkevich, a developer and one of the first Kufar employees.