Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

Machines Like Us - A brief history of artificial intelligence

From horse manure and monsters to inscrutable language models. The dream of artificial intelligence is as old as myth itself. But why are we so eager for artificial minds to replace our own?

By Sam Sundberg

“AI is a bigger threat than climate change”, “AI could cause ‘civilisation destruction’”, “Humanity is failing the new technology’s challenge.”

As OpenAI launched ChatGPT in 2022, not only did people envision amazing new ways to use the technology for the good of humanity, but many AI scientists expressed grave concern that the technology would be used to flood the internet with disinformation or worse, that machine intelligence was about to surpass human intelligence, presenting questions we are not yet ready to answer.

Many have speculated that low-level jobs will soon be taken over by AI. But no longer are only simple, repetitive occupations at risk. Lawyers, physicians, artists, writers… as artificial intelligence approaches the human level we all should worry about – or look forward to – machines replacing us in the workplace.

I recently spoke to Max Tegmark about these developments. He is the author of “Life 3.0,” a professor at MIT and a renowned AI expert, and he is profoundly worried. Tegmark has been campaigning against nuclear weapons for years, but at present, he considers artificial intelligence an even greater existential risk. If we choose to replace ourselves, and let machines do all our work for us, the human species may simply lose the desire to carry on and to procreate. But why, Tegmark wonders, would we want to replace ourselves with machines?

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

Ada Lovelace is often described as the first computer programmer and is said to have created the first algorithm created to be processed by a machine.

In fact, this question echoes through the ages: Why have scientists and alchemists for so long strived to create not just useful machines, but machines like us?

The pursuit of artificial intelligence is not about merely making efficient tools, like calculators and word processors. It is about mimicking human intelligence, a quest to equal or even surpass it. In essence, turning the myth of creation on its head, making humans the creators of new life through intelligent design. This dream has ancient roots.

An awesome bronze giant

The Greeks told of the divine smith, Hephaestus, who forged automatons to serve its masters. Talos is the most famous of his creations, an awesome bronze giant who patrolled the island of Crete, protecting it against pirates. At Alexandria, the Egyptian scholar Heron built a spectacular array of automata for the theatre. Not intelligent, naturally, but appearing alive.

Around the thirteenth century and onward, many learned men, scholars and occultists were rumoured to possess mystical contraptions known as “brazen heads,” mechanical heads covered in bronze, which could answer any questions put to them. This may have been a legend borne out of the ignorance and jealousy of their scholarly wisdom. No evidence of any scientist or magician creating such a device exists. But soon automatons of a less supernatural kind became all the rage among the European aristocracy.

These cleverly constructed machines were no more than mechanical divertissements made of cogwheels and springs, inspiring awe and wonder. Magic tricks, to entertain guests, rather than actual dark arts. But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

But alchemists and occultists were still hard at work, exploring the possibilities of creating some form of intelligent beings.

Indeed, in the sixteenth century, the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus claimed to have created a living, breathing homunculus by burying human sperm in horse manure for 40 days, magnetizing it, and then feeding it human blood for 40 more weeks. This little humanoid was said to work as an assistant to its master. Paracelsus promised, in words that could very well refer to the creation of artificial general intelligence far in the future:

“We shall be like gods. We shall duplicate God’s greatest miracle – the creation of man.”

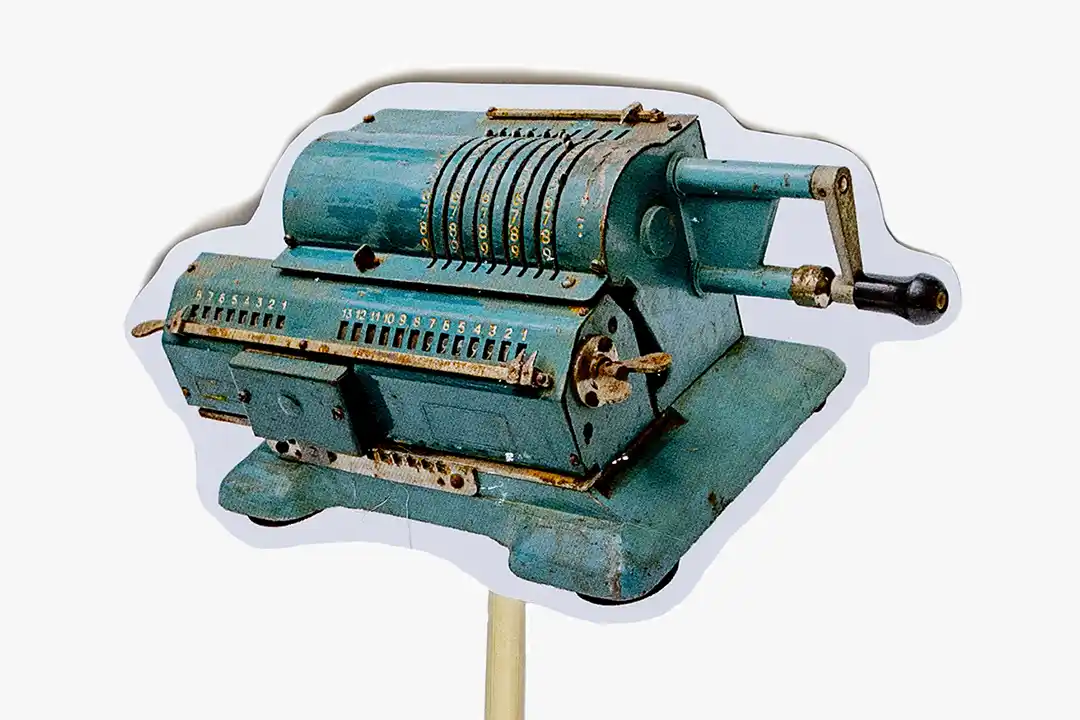

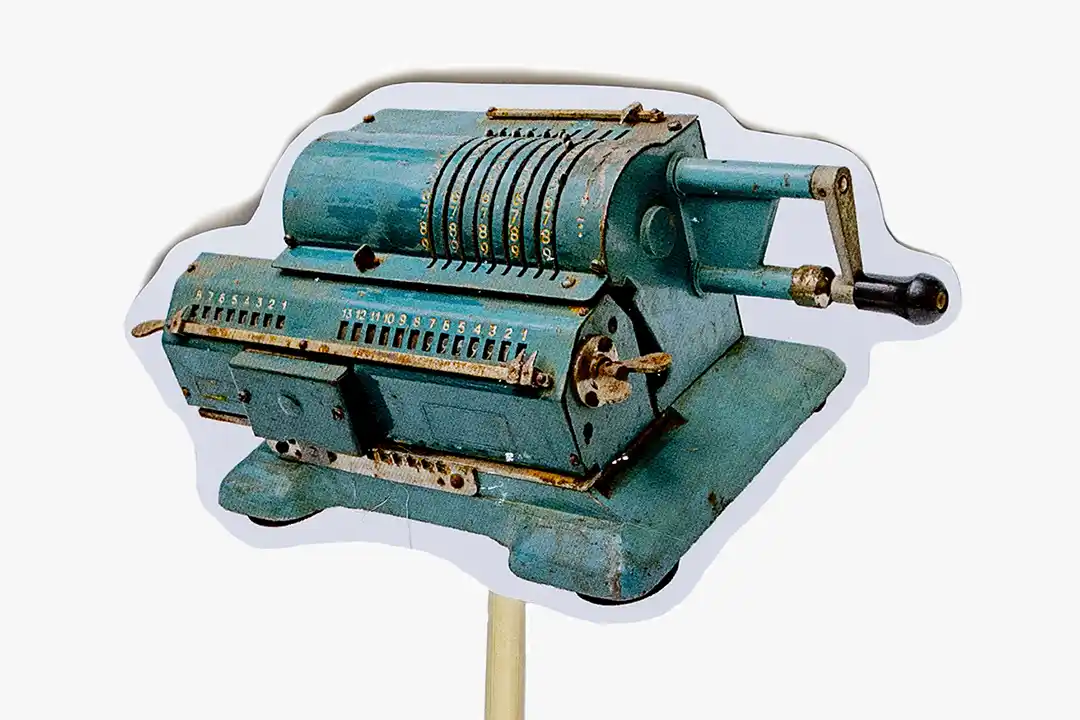

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

Throughout history mankind has strived to create useful machines. This is a mechanical pinwheel calculator.

In 1818, a sensational horror novel was released that tickled the imagination of thousands of readers. “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley, is the tale of a modern scientist following in the footsteps of alchemists like Paracelsus, consumed by the idea of creating an artificial man through scientific means. The Italian biologist Luigi Galvani had recently discovered that electricity is the means by which the brain sends signals to the muscles, so Shelley had Viktor Frankenstein animating his creature by electric current from a burst of lightning. The result, of course, is Frankenstein’s monster – a huge man, terrifying to its creator and woefully unhappy, who goes on a murderous rampage. The tale may serve as a warning of humankind’s troubles in controlling their greatest inventions.

Starting point of modern computing

Many historians would cite Charles Babbage’s designs for the Analytical Engine as the starting point of modern computing. In the 1830s, Babbage, a British inventor, engineer and mathematician, came up with two designs for machines capable of performing mathematical calculations. The first, called the Difference Engine, was funded by the British government and Babbage himself, but the project was never completed.

The second, called the Analytical Engine, was even more ambitious, and funding was hard to come by. Along with his companion Lady Ada Lovelace, he came up with different schemes to fund the project. At one point they proposed a tic-tac-toe-playing machine to entice investors, then they considered building a chess machine. Before they could build it, however, they came up with an even better idea. They would build the perfect system for betting on horse races, to fund the completion of the Engine. The scheme was meticulously planned by some of the brightest minds in England and ended in spectacular failure. Soon Lady Lovelace was deep in debt and rescued not by any ingenious machines but by her kind mother.

The Analytical Engine, like its predecessor, was never completed. But Babbage’s designs, along with Lady Lovelace’s ruminations on how the Engine would in theory be able to not only calculate numbers but to have those numbers to represent anything – for instance sounds in a musical composition – was an important step in the creation of the universal computer.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

Technology shifts sometimes happens fast. Devices that not too long ago seemed very modern, can quickly go out of fashion.

It would be another century before such a computer was finally realised. The world’s first programmable computer was built in the late 1930s by the German engineer Konrad Zuse. He called the mechanical, motor-driven machine the Z1. Although it was the first computer to be finished, many other engineers were tinkering with computers around the world. At this time, the field of psychology was also starting to understand the human mind as a biological network, and piece by piece figure out its workings. Perhaps the brain was best understood as a machine? And if so, might not a machine such as the computer, in the future, be able to perform the same work as the brain?

With these questions in mind, scientists were again starting to entertain ideas about thinking machines, mimicking human thought and behaviour. Their ideas were collected under names such as “cybernetics,” “automata theory” and “complex information processing”. It was not until 1956 that the American scientist John McCarthy came up with a new name for the field, that proved to be sticky: “artificial intelligence.” That summer he joined 19 other prominent academics at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire for a workshop brainstorming about the exciting new field.

Creating a computer mind

The participants of the conference were engineers, psychologists, neuroscientists, mathematicians, physicists and cognitive scientists; an interdisciplinary brain trust well suited to taking on the challenges of creating a computer mind. Their mission statement – brimming with the naïveté that comes from not yet having tried and failed – outlines their lofty ambitions:

“Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans and improve themselves.”

The participants were confident that they would make great strides in this direction during the two-month workshop. It would be a stretch to say that they achieved their goal, but during those long discussions at the Dartmouth Math Department, they at least firmly established the new field of AI.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Mechanical divertissements, made of cogwheels and spring, to entertain guests were popular among European aristocracy.

Human-level machine intelligence would turn out to be far harder to achieve than the early pioneers imagined. During the following decades, AI hype would be followed by AI winter in a cyclical pattern. Several prominent AI researchers, among them Marvin Minsky, had predicted human-like intelligence by the 1980s. When those predictions were proven wrong, some were deflated, but the Japanese government was eager to have Japan take the lead. In 1981, Japan initiated the Fifth Generation Computing Project, pouring 850 billion dollars into AI research, with the stated goal of creating machines that could carry on conversations, translate languages, interpret pictures and reason like human beings.

Progress was made during this time, primarily with limited systems tuned to play chess or give expert advice in narrow fields of inquiry. But anything even vaguely resembling the dynamic and wide-ranging intelligence of humans remained out of grasp. After the Fifth Generation Project came to an end, without fulfilling its promise, the field again found itself at a low point late in the 1990s.

Luckily, an offshoot of AI research was about to gain new traction. In parallel to the mainstream research going on at prestigious universities, well-funded government programs and hyped-up companies, some scientists had taken an interest in artificial neural networks. The network architecture was thought to resemble the human brain, offering new ways of representing machine thoughts compared to the strictly algorithmic manipulation of symbols of conventional AI systems. A neural network could be trained on appropriate data sets, much like a child learns, until its maze of internal connections becomes suitable for its designated tasks.

A fatal flaw

Artificial neural networks had a fatal flaw, however. As soon as you started to scale a network to do something interesting, its complexity increased exponentially, and the system ground to a halt. The computer hardware of the time, with architecture very different from human brains and far less processing power, simply could not keep up. So, this line of research remained theoretical, dormant for decades until, deep in the 2010s, the time had come for the AI field to enter a new era of machine learning.

Three developments of the new millennium came together to finally make neural networks practical:

Computer hardware kept getting faster, smaller and more energy efficient, as predicted by Moore’s Law.

Computer scientists developed more sophisticated architectures and algorithms for artificial neural networks.

An immense trove of digital text, images and sounds accumulated online, an all-you-can-eat buffet of information for neural networks to be trained on.

Looking back at what was then envisioned, artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name.

With the recent work of DeepMind, OpenAI, Google and Microsoft, we arrive at today’s state of the art. Artificial intelligence may have missed the deadline of Japan’s Fifth Generation Project, but looking back at what was then envisioned – or indeed, what the Dartmouth Workshop sought to achieve – artificial intelligence is finally living up to its name. ChatGPT and its rivals can easily hold conversations with humans; Google Translate and its ilk can translate text and speech in the blink of an eye; and many neural networks not only interpret images but also create beautiful pictures from natural-language prompts.

Several fundamental questions do remain, however. Can these machines truly reason? Can they think? Can they feel? Will they ever?

The French seventeenth-century philosopher René Descartes famously formulated a dualist theory where mind and body are metaphysically separate. He was inspired by the automatons on display in Paris at the time and concluded that mind and body must be different substances. The latter can be replicated by automatons, while the former is singular to man and intimately tied to what makes us us. We think, therefore we are.

Unexpected leaps

With AI science advancing – at times inching forward incrementally, sometimes striding with unexpected leaps – software engineers are getting closer to imitating the human mind as well. Chat GPT has repeatedly defeated the Turing test, designed by the British computer pioneer Alan Turing to settle the question: “Can machines think?”

Refined algorithms, humongous data sets and clever reinforcement learning techniques are pounding at the walls of dualism. Perhaps, as the Dartmouth Workshop proposed, the human mind is a mere machine after all. And if this is the case, why would we not be able to replace it with more efficient machines?

The history of artificial intelligence is a tale of scientific progress, of engineering failures and of triumphs. But it is also the story of our struggle to understand our own minds. Are we truly unique? Are our brains, like our bodies, simply machines governed by electrical impulses? When we dismiss the “thinking” of large language models as simply a series of predictions of what comes next, are we absolutely certain that this does not also apply to human minds?

It seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already.

At this point (as at every point in the history of AI) it seems inevitable that we will soon be able to create genuine thinking machines – if we haven’t already. There is still some disagreement about whether we can create feeling machines, however. Conscious machines. Machines that can do and experience everything that a human can and more.

Some aspects of this may be harder than we can foresee. On the other hand, it may be within our power sooner than we think, emerging incidentally as our models become increasingly complex, combining techniques from neural networks with symbolical AI.

Mary Shelley would be delighted to see modern scientists still hard at work trying to realise the ancient dream of godlike creation. The full original title of her famous horror novel is “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.” The subtitle alludes to the crafty Titan from Greek mythology who stole fire from the Olympian gods and gave it to man. Fire, in this old tale, symbolises knowledge, invention and technology – powers Zeus had determined must be reserved for gods and withheld from humankind.

In some versions of the myth, Prometheus gives us more than fire; moulding the human race from clay, he also gives us life. Millennia later, the fire he gave us is still burning bright, and we are now the ones doing the moulding. Not from clay, but from code.

[Sassy_Social_Share]

Sam Sundberg

Freelance writer, Svenska Dagbladet

My favourite song the last decade: Light years – The National