Future trends for regulating the digital economy

Today we live in a very different world than we did just a few years ago. Everything has changed: the geopolitical landscape, the energy market and the cost of living. What has also changed is the view on regulating the Internet.

Some years ago, most politicians in the Nordics believed that the Internet should be free of rules and that a liberal regime was the only true guardian of innovation. Tech companies should not be liable for the content on their platforms and big tech should be able to grow by acquiring start-ups.

The pendulum has now swung to the other side, and in 2022, we see overwhelming support from Nordic decision-makers for the EU landmark regulations over the digital landscape, namely the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA).

Both regulations were adopted by the EU in summer 2022, and they will become reality by early 2024, at the latest. These instruments will have a huge impact on the way platforms deal with liability for illegal content, as well as how big tech companies should deal with their business users. The guiding principles for the new regulations are focused on creating fair and transparent rules that level the competition in the market and protect users and consumers from unfair commercial practices.

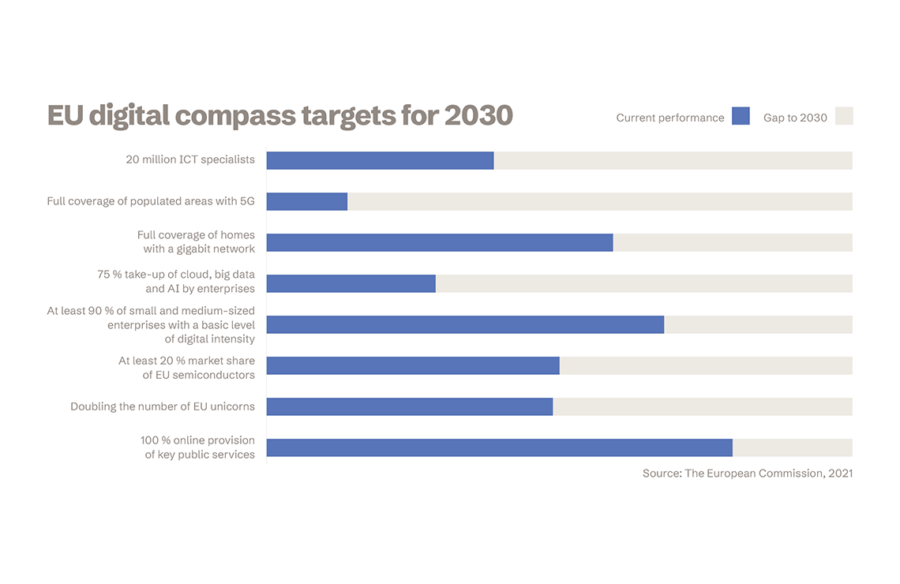

The current EU Commission is now halfway through its mandate and has already achieved a lot by means of proposing new digital regulation and becoming a force against the big tech companies. The Commission has set up several goals for 2030 related to increasing tech talent and the number of European unicorns, but they still have a long way to go to meet their goals.

But while the EU wants to boost the European digital economy, it also wants to create a safe internet based on European values. This is a tricky balancing act between those who want liberal rules that allow for innovation and increased global competition, and those who want heavy regulation that protects the consumers of digital services.

The EU’s objective can be summarised in two words: values and sovereignty. Or in the words of Commission president Ursula Von der Leyen: “Digital sovereignty is not just an economic concept. We are a Union of values. One of the great questions is: How can we preserve and promote our values in a digitised world?”

Recent global events have undoubtedly strengthened the belief among EU policymakers that the EU needs to be its own strong force and promote a distinct ‘third way’ of regulating the digital economy, somewhere in between USA’s ‘laissez-faire’ approach and Chinese authoritarianism.

This will – and has already – led to more regulatory oversight and enforcement powers at the EU level, making Brussels an increasingly important hub of tech regulation. This centralisation will make the European Commission a bigger interventionist player in the digital economy, not only by proposing new legislation but also by monitoring and ensuring compliance, which will take responsibility away from national authorities and make the rules even more harmonised across the EU.

Based on this new landscape, there are four major regulatory trends that will set the stage for the coming Internet rule book.

Safeguarding EU values

This EU Commission is much more political and principals-based than previous Commissions. It has taken the fight with the big tech, at the urging of France, but it is also taking a political stance against countries such as Poland and Hungary that are an increasing source of irritation to the Commission and other Member States with their populistic and nationalistic agenda.

As part of this battle, the Commission wants to protect the European value of freedom of expression, enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, by introducing a proposal that aims to protect the safety of journalists and the independence of newsrooms from any external influence, such as states, owners and platforms.

This proposal will be much debated, as regulating the media is a sensitive issue that typically is left at the national level. The fact that the EU Commission is considering a proposal to regulate media on EU level shows that it will do anything to protect the values that it holds dear. But it will be an uphill battle to defend this proposal against member states and media companies that oppose any regulation of freedom of expression beyond the national level.

Protecting consumers, minors and privacy

One of the most discussed and contested issues in digital regulation is the use of personal data for targeted advertising. Many EU decision-makers are frustrated with the slow and inefficient enforcement of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the need for a targeted revision of the rules is under discussion. The DSA and the DMA have already included specific rules to ban targeted advertising directed towards minors and stricter consent rules for digital gatekeepers, but there is a clear political push to do more to protect privacy.

We also see a continued push from EU institutions towards greater transparency regarding the use of algorithms, with the aim to ensure that people are empowered and informed about them. And similarly, we expect some moves to regulate the use of so-called ‘dark patterns’ and platform designs that are perceived to manipulate and steer user choice and inhibit freedom of choice online.

Fostering EU innovation

The European Commission will propose a series of legislative measures to strengthen the EU’s position as a hub for emerging technology innovation. This is expected to include a review of the regulatory definitions of ‘start-ups’ and ‘scale-ups’ in 2023, intended to promote the emergence and success of EU technology companies. On the one hand, these measures are an attempt to make it easier to create new digital services, through a common EU digital identity and a review of EU competition policy, ensuring that competition instruments (merger control, market definitions and State aid control) are fit-for-purpose in a fair and balanced digital market. On the other hand, the EU will also look at regulating new technologies.

One example is the AI Act that is currently under discussion, in which the EU aims to regulate a technology that is still developing. The objective is to scrutinise certain AI technologies that can be seen as high-risk, such as facial recognition. But some are also of the opinion that AI used in newsrooms, such as bots and computer-created images, should be seen as high-risk AI, as the content may not be trustworthy and therefore in need of heavy regulation.

Promoting a circular economy

The EU’s ambition to be climate-neutral by 2050 remains the guiding policy for the green transition, which has also impacted digital regulation. The EU Commission has adopted a package of proposals for the circular economy, empowering consumers in the green transition and making sustainable products the norm.

A key proposal on Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) introduces (among other things) a digital product passport for new products, as well as certain requirements for online marketplaces.

The EU will also propose a regulation on Right to Repair this autumn that will require products to be repairable and, as a result, prolong the average product lifetime.

At the same time, there is enormous political pressure to increase product liability of online marketplaces, which could include liability for green claims of products.

Schibsted’s voice

Schibsted is a leading voice and will actively contribute to a regulatory landscape that allows for the innovation of state-of-the art digital products and services in the Nordic market. We will focus on calling for effective implementation and enforcement of EU regulations, such as the DSA and the DMA, and ensuring balanced regulation for online marketplaces, as well as the continued ability to use data to create of relevant products and services for our users. We will defend editorial independence from external influence and the Nordic self-regulatory system in the media. And we will support efforts to promote sustainable products and circular consumption in Europe.

Petra Wikström

Director of Public Policy

Years in Schibsted: 4