Next generation

If you think the step from print to digital was challenging, prepare yourself: The next leap for publishing and journalism is far bigger, more complex and way more exciting. It’s about going from one-size-fits-all journalism to 1:1 journalism, says Espen Sundve VP Product Management at Schibsted.

All publishers are at a crossroads, whether they want to admit it or not. They are left with a simple choice: either lead the charge to redefine journalism and their products, or become mere content providers for external platforms, making them the de facto publishers of our time. To put this in Matrix terms I know my tech peers can relate to, publishers need to choose between the red pill or the blue pill.

Taking the blue pill means moving deeper into a role as pure content creators for third-party platforms – platforms that dictate the editorial and business rules without claiming any editorial and financial accountability for independent journalism. The drawbacks of this direction are pretty clear – this results in a great concentration of power around the platforms.

Taking the red pill means facing reality and creating an alternative – a reality in which the publishers reinvent their established products to remain relevant as destinations for their readers. A reality in which accountable editorial voices define the technology, and algorithms are used to serve and fund independent journalism.

Taking the red pill means taking a leap and reinventing established products into a new publishing suite that will be successful in the user engagement battle for years to come. At Schibsted we think of these as our Next Gen Publishing Products. But we’re no longer big enough to do it alone. None of us are. Either we all make this leap together, or we all end up swallowing the blue pill.

Strong digital positions

It’s not like publishers have completely missed the mark with established digital products. Many of us have managed to build strong digital positions for our established brands. But let me share a few of the established ”rules” that seem to prevent us from radical leaps towards a more engaging user experience:

- We create pieces of content meant for everyone, and manually curate our front pages.

- We have adapted the old print user experience to a desktop format, and later the desktop user experience to mobile.

- We’re content-centric in all that we do, not user-centric. One example: The user interaction model is to navigate by topic or format (not by user mode), and we primarily care about pageviews (not user events).

- We originate all content ourselves, making the idea of being deeply relevant to a very broad audience a very expensive affair

- Advertising is produced, served, presented and tracked outside the editorial content and technology solutions – resulting in a cluttered and slow-loading user experience.

- Journalists, business developers, designers and engineers devise and implement ideas to improve aspects of the product without working together, with no one responsible for the total product.

When we look at trends in consumption of online content and the ”rules” holding us back, we can sum them up in one major bottleneck: we are still broadcasting journalism, while new digital content distribution platform players such as Facebook and Google are offering deeply personal experiences.

But instead of merely throwing out the buzzword ”personalization” and pretending that we’ve found the solution, it’s essential to start by asking ourselves why we engage in journalism in the first place. How can our journalism be 10x or 100x more relevant if we could tailor it to each individual reader?

The true purpose of journalism

Being a technologist and somewhat new to the media industry, I’ve spent a lot of time recently trying to understand the true purpose of journalism. This is important, because if we technologists do not fully adhere to the foundational principles of journalism, we can never truly join forces with the newsroom. I’ve realized I can express the purpose of journalism in a way that will resonate with any technologist – as an optimization challenge:

Journalism exists to minimize the gap between what people already know and what they should and/or want to know – so that people can make informed decisions about their personal life, community, society and governments.

To help close that gap, we can simplify and say we do three jobs for the end user:

- We connect the user with a story

- We tell the story

- We engage and involve the user

To make the leap from broadcasting to 1:1 journalism, we have to innovate along all three of these dimensions. With a one-to-one relationship with each (logged in) reader, fueled by data collected on their behavior, context and preferences, we should be far more sophisticated in optimizing what we show to whom, and when and where we do it. We have two major advantages in this game vs. Facebook and the like.

First, we can be fully transparent in how we curate. We embrace editorial responsibility, so while tech platforms leave the user in the dark as to how content is filtered we can dare to be open about why and how we curate to close the gap between what you know and what you should (or want to) know. Second, we have journalists and editors and their inherent curatorial skills: While Facebook pays 30 contract workers and have 700 reviewers around the United States that assess and train the news feed algorithm, the publishing industry collectively has thousands of the world’s premier content experts – the journalists. By incorporating their assessment and know-how into algorithms defined and owned by publishers, publishers should be well-armed in the fight for user attention.

New form of storytelling

In telling stories, we currently create a single story for everyone. We believe media and journalism should break with this and invent a new form of adaptive storytelling. As the creators of content, we can and should capitalize on the competitive advantage we have over players like Facebook. The Facebooks of the world do not produce their content, they primarily focus on how to personalize the filtering of it.

Publishers, on the other hand, can start to personalize down to the level of content creation. Ideally, the stories I read should match my level of insight, interest, and past behavior within every topic, my preferred way of being informed (say, pictures over text), my current context and more.

If newsrooms dare to rethink what they produce (such as leaving articles behind for something more granular), journalism will be far more relevant. In engaging an audience, we’ve always invited them to contribute with opinion pieces and tips; recently, we’ve begun offering share buttons and comment fields next to our articles. Beyond that, we’ve mostly outsourced engagement to social media.

Technology companies are great at bringing users on a journey and connecting them for discussion. If media companies had better insights and data on their users, they could be far more sophisticated in how they tailor engagement options to users depending on their behavior, preferences and context. This would not only increase distribution and reach of the content, it could also provide valuable audience input to enable the newsroom to create even better journalism.

A personal editor

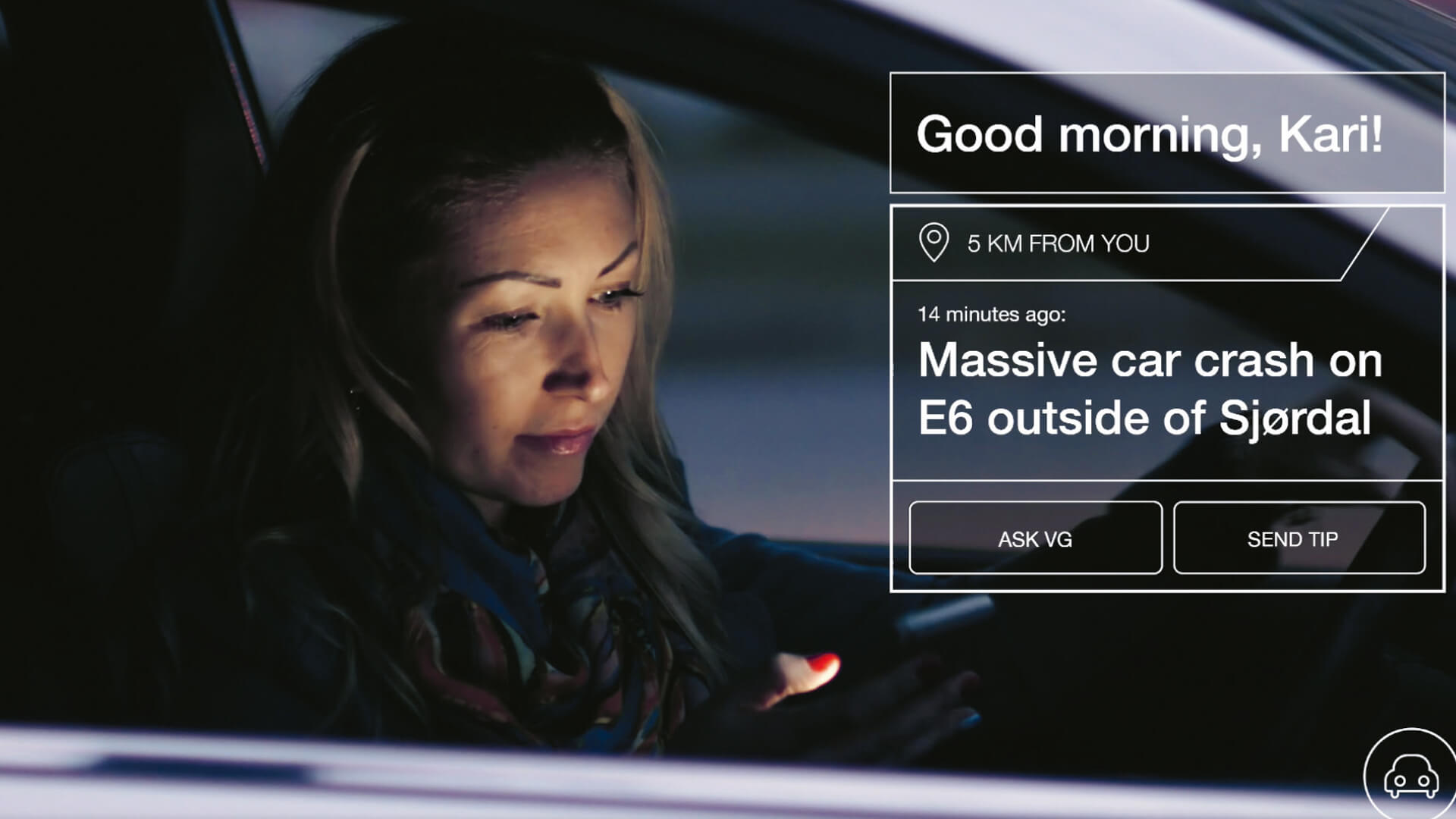

For our next-generation products, Schibsted has formulated a vision: They should deliver and tell news in a way that makes users feel like they have their own intelligent personal editor. Let’s pause for a moment on the word “editor.” The rise of pure tech platforms as a primary source of journalism and opinions presents us with a serious societal challenge. Tech platforms inherently neglect editorial accountability, and also do not curate content with any mission to challenge individuals with what they should know.

To define an intelligent personal editor, we mean:

- An editor who optimizes her algorithms, for example making sure some news reaches everyone, while other news reaches only the right niche audience.

- An editor who can help people understand complex, contemporary issues through personalized storytelling, matching each individual user’s preconceptions to understand and engage with the story.

- An editor who intelligently guides the user through a world of information overload, selecting and presenting relevant content from various sources.

- An editor who can be trusted to give users a balanced view of the world, avoiding filter bubbles while fostering dialogue.

- An editor who knows how to surprise and entertain users, not merely challenge and enlighten them.

- An editor who allows advertising to have the same great user experience as journalism.

- An editor who ensures that the user has a seamless experience across any device.

Let’s be clear: We do not yet have the magical roadmap that shows how we’ll get to 1:1 journalism. But we’re determined to build, test, validate, and fail or scale new products, processes and experiences.

If any of us are to be successful at curating relevant experiences for each individual user, we have to be able to pull from a wider volume of content. And not just any kind of content, but quality journalism, which can only be achieved by media companies making all content available to all other publishers. Furthermore, only by sharing user engagement data collection can we gain the full user insight we need to rival the data power of tech platforms. Not only do we need to collaborate on capturing data to be competitive in the advertising market, but we also need to allow the free flow of content between our brands to be more relevant and to maximize our collective reach.

Our curation process is still largely manual. Moving from print to digital, we invented “front editors.” Now we have to do it again, but this time, our front editor needs to tune algorithms rather than words and pixels. Instead of defining placement and format in curating content, they should be concerned with defining user segments.

Content creation as a weapon

The third hurdle lies in the way we create our content. In particular, we need to go beyond articles. The key issue is that our current formats don’t allow for adaptive storytelling – storytelling in which we adapt to users’ knowledge (what they’ve already read), interest level, context and more. Circa News paved the way for atomizing news, and the NY Times has written about particles in their blog. Furthermore, with conversational news apps paving the way for bots, our old article format simply won’t cut it. As tech platforms compete for user attention by redefining content distribution and engagement, our greatest weapon in the fight for relevance could lie in our core task – content creation.

Fundamentally, if we want to be better at engaging each individual user – bringing them on a journey from fly-by readers to a loyal and actively engaged audience discussing and adding value to the stories, we have to know who our user is. As of now, we don’t. The challenge to solve here is to give users compelling reasons to be identified (logged in). In doing so, we have to move beyond mere vanity features (”save this article for later”) and marketing campaigns (”log in to win an Ipad” or “get premium free for a week”). We have to make our product experience better if you’re identified, and this requires making journalism personal.

We are at a point where media and journalism have to take a stand. Publishers either must submit to the new rules defined by the pure tech platforms, giving them our content and data and making them stronger every day, or they must decide to evolve journalism into something that truly embraces the opportunities we have – the chance to invent true 1:1 journalism.

As we have evolved to move from print to desktop and from desktop to mobile, we now, together, must decide to embark on the mission to reinvent ourselves once more – at our core – before someone else does it for us. That is why we are investing in Next Gen Publishing products, because journalism is not disrupted by digital. It’s enabled.